What’s better than a good story? A good, scandalous story. Enthralling tales fill the halls of literature, but they often pale in comparison to the real-life stories behind their creation. Authors seem to fall prey to all the usual human frailties, only more so: Lust, cruelty, selfishness—not to mention the strange blend of insecurity and arrogance that can lead a writer to think they can get away with stealing. They are all here on display in these 42 page-turning facts about literary scandals.

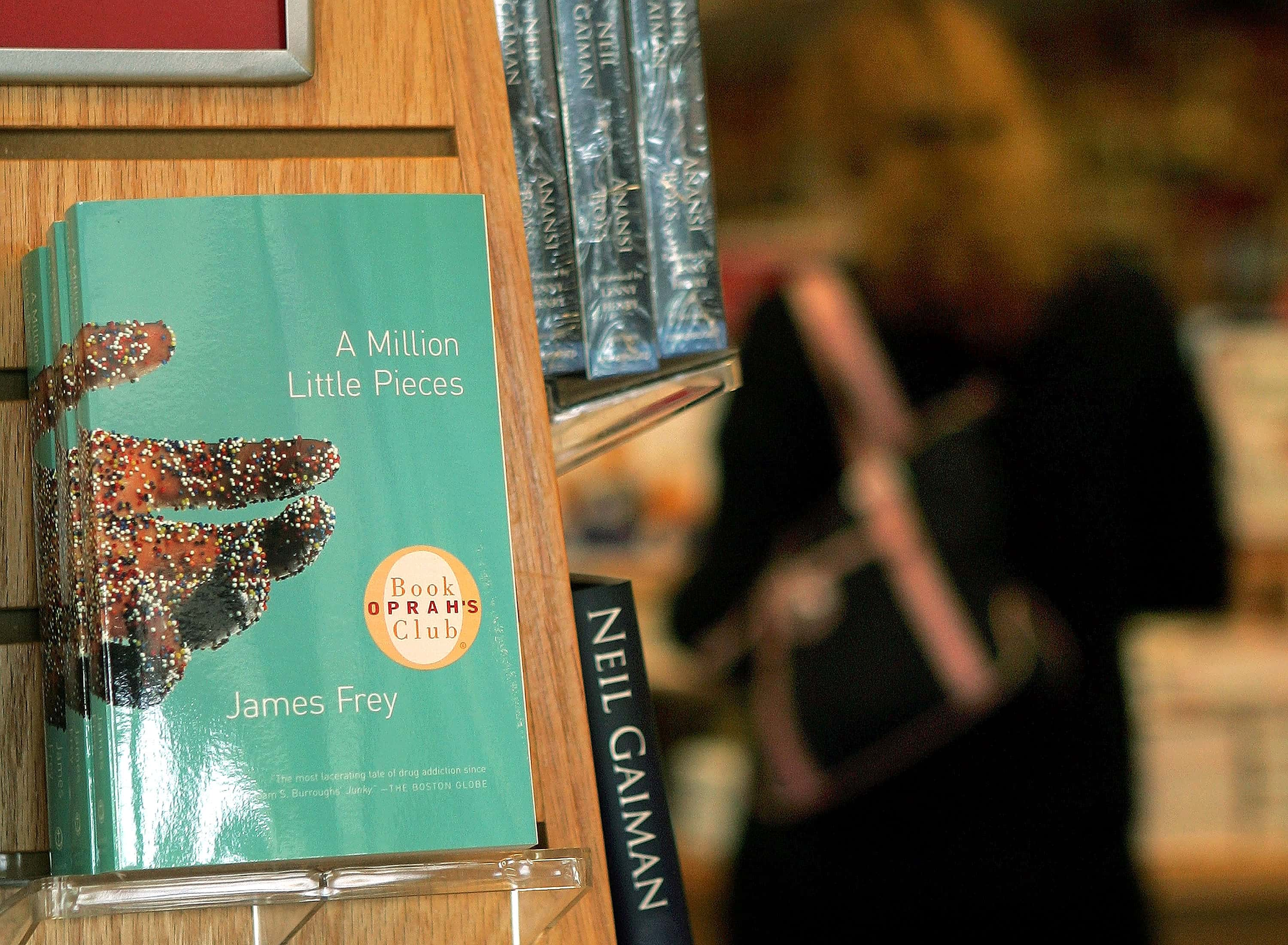

1. A Million Little Problems

James Frey’s literary star was on the rise in 2003. His first memoir, A Million Little Pieces, which detailed his time as a recovering drug addict, was handpicked by Oprah for her Book Club, and subsequently spent 15 weeks atop the New York Times Best Seller list. There was just one problem: It was all a lie.

2. Caught Red Handed

At the height of Frey’s popularity, online newspaper The Smoking Gun published a story exposing him as a fraud. Significant portions of Frey’s “memoir” were exaggerated, stolen, or outright made up. Frey admitted to massaging some of the details for the sake of the story, but nevertheless stood by his book. As you can imagine, that did little to stop the gossip mill...

3. Brought Before the Queen

No matter what Frey said, the damage had been done. A Million Little Pieces vanished from bestseller lists and bookstore shelves—but that wasn't the most painful part for its author. Oprah famously summoned Frey to appear on her talk show to personally apologize to her.

4. A House in Ruins

Frey’s publisher did not escape unscathed either. After admitting they did no fact-checking into Frey’s story before publication, Random House actually offered refunds to dissatisfied readers.

5. Happy Endings?

One would think this would be a career-ending catastrophe for Frey. Not so. In fact, he's released several bestsellers since then. His most recent book, Katrina, came out in 2018. Not only did A Million Little Pieces see a rerelease (though this time, reclassified as fiction), director Sam Taylor-Johnson even made a movie adaptation in 2018, starring her 23-years-younger husband Aaron Taylor-Johnson.

6. Fencing Match

This was not the last time Oprah had to face a literary fraud. Herman Rosenblat’s unpublished Holocaust memoir, Angel at the Fence, won praise from the daytime TV star, who called it “the greatest love story ever told.” Before the book could even be published, however, historians had already poked enough holes in Rosenblat’s story to sink his publishing deal.

7. Of All the People

As an executive editor at the esteemed publishing house W.W. Norton, Jill Bialosky wields considerable power in the literary world. Poet William Logan was certainly punching up then when he wrote a scathing review of Bialosky’s memoir, Poetry Will Save Your Life. Not that Logan’s criticisms were without merit: As Logan pointed out, Bialosky lifted several passages almost verbatim from other sources—including Wikipedia.

8. Friends in High Places

The charges shocked the literary community. And while many joined Logan in his condemnation of Bialosky, it wasn’t long before a number of high-profile poets were jumping to her defense, among them Louise Glück, Robert Pinsky, and Joy Harjo. In all, 72 well-known writers signed a letter dismissing Logan’s claims and excusing Bialosky’s behavior. However, we should note, nowhere did the letter state the claims were untrue.

Apparently, plagiarism is OK—if the literary world likes you enough.

9. Luck o’ the Irish

William Ireland was just 19 when he managed to convince the literary world that he had found a hoard of letters, poems, and even some unpublished plays by none other than William flippin’ Shakespeare. Ireland’s father was a well-known rare book dealer, so perhaps it didn’t seem outside the realm of possibility.

10. The Play’s the Thing

The jig was up when Ireland attempted to stage one of these lost plays, “Vortigern and Rowena.” The play was so laughably bad that critics instantly realized that Ireland wrote the plays himself. Apparently, he was a more skilled liar than he was a writer.

11. Father of the Year

Don't worry, at least someone had Ireland's back. His father, who had published most of the findings, stood by his son. His rationale: The younger Ireland was simply too stupid to have written a play.

12. Telling It Like It Is

Mary Wollstonecraft, one of the most forward-thinking writers of her era, was an ardent feminist. So was her husband, William Godwin. It only made sense to Godwin, then, that his memoir about his recently deceased wife should depict her accurately. Unfortunately, 19th century English readers couldn't exactly handle the messy truth about her...

13. We Don’t Know Her

Godwin’s Memoirs of the Author of a Vindication of the Rights of Woman were, to put it lightly, juicy. They featured frank depictions of his wife’s life, including a child born out of wedlock, several suicide attempts, and a number of illicit affairs. The allegations so scandalized even radical readers that, for a century after, feminists actively distanced themselves from Wollstonecraft.

14. Don’t Say I Didn’t Warn You

The outrage was all very predictable, of course. In fact, Joseph Johnson, publisher of Memoirs of the Author of a Vindication of the Rights of Woman (as well as Wollstonecraft’s original work) urged Godwin to temper his depictions of Wollstonecraft. Godwin refused. Depending on how you look at it, in doing so, he either truly honored one of the most divisive thinkers of the day, or doomed her reputation for a century after.

15. Queensberry Rules

Oscar Wilde, Irish playwright, poet, and one of the wittiest men who ever lived, made a career of satirizing English manners and society. However, Wilde made the mistake of pursuing a high-ranking member of English society—Lord Alfred Douglas. When Lord Douglas’ father, the Marquess of Queensberry, found out about the affair, he had Wilde apprehended for gross indecency. But this wild scandal was only beginning.

16. Hard Time

Wilde’s sexuality was hardly a secret among the literary community, but the public morality of the Victorian era guaranteed that judges would make an example of him. They sentenced him to two years hard labor, the maximum allowable sentence, the judge lamenting that the sentence could not be harsher.

17. What’s a Gaol?

Wilde spent his two years being shuttled between a number of prisons around England. Back in those days, "hard labor" consisted of walking endlessly on treadmills or picking apart tough old Navy ropes for no reason. Not the most fun, but at least the two years were not a total loss: During his sentence, Wilde composed “The Ballad of Reading Gaol,” considered one of his finest literary accomplishments.

18. Audio Books

Jean Shepherd, a New York radio personality, was an outspoken critic of the literary and publishing worlds. He particularly hated that book requests counted toward book sales on bestseller lists. Finally fed up, Shepherd asked his listeners’ help in pointing out the flaw in the system. The following morning, an army of Shepherd’s listeners arrived at bookstores across New York City to request a copy of I, Libertine—a book that did not exist.

19. All Sold Out

These ludicrous requests caught bewildered booksellers off guard. They began frantically calling distributors and publishers, trying to find out where they could get a supply of the suddenly popular I, Libertine. Even though they continually came up short, I, Libertine nevertheless climbed the New York Times Best Seller list.

20. Stranger Than Fiction

The hoax was so successful that it actually resulted in Ballantine Books publishing a book called I, Libertine. Ballantine hired a writer to rush together a manuscript in order to capitalize on the craze.

21. Mail Tears

Robert Lowell's “confessional” style of poetry made him famous, but he had a dark side. He managed to outrage even his most devoted supporters when he altered excerpts from his wife’s letters were and used them in poems for his 1973 book, The Dolphin.

22. I Just Met You, and This is Crazy

Lowell’s wife, literary critic Elizabeth Hardwick, had written those letters in a failed attempt to save their marriage. Lowell and Hardwick spent 23 years together when he suddenly left her for Caroline Hardwick, an English heiress and model 15 years his junior. Lowell had known Hardwick exactly one night when he moved in with her.

23. The Whole Truth

Most of Lowell’s literary friends sided with Hardwick in the split—but no one realized how low he'd stoop. People couldn't believe it when Lowell published excerpts from Hardwick’s letters as parts of his own poems. Adrienne Rich called it cruel and appropriative. Even fellow confessional poet Elizabeth Bishop chastised Lowell: It was bad enough to use them in the first place, she said, but changing them was unforgivable.

24. Nice Guys Finish Las

Despite criticism from many high-profile (primarily female) writers, The Dolphin went on to win the 1973 Pulitzer Prize.

25. Spilling the Tea

Greg Mortenson’s memoir Three Cups of Tea recounts how, having suffered an accident while mountain climbing, Mortenson finds himself in an isolated Afghan town occupied by the Taliban. Later, Mortenson repays the town’s kindness by returning to build a school. A remarkable story, Three Cups of Tea stayed on the New York Times Best Seller list for four years—and I bet you can guess where this is going...

Eventually, large portions of the book were revealed to be inaccurate or completely fabricated.

26. School’s Out

Among the claims printed in Mortenson’s book, sleuths proved many of them completely false. The mountain climbing accident which begins the story never happened, nor did the Taliban kidnap him—indeed, the Taliban did not occupy that part of Afghanistan at the time. And while Mortenson’s foundation, the Central Asia Institute, did at least begin to build schools in the region, many were left unfinished or disused. But that's not even the worst of Mortensen's behavior...

27. IOU

Following these revelations, an investigation into the Central Asia Institute found that Mortenson had misappropriated more than $6 million from the foundation. The courts didn't end up finding any actual wrongdoing, but Mortenson ended up paying back $1 million—out of the goodness of his heart I guess?

28. True Believers

Mortenson’s co-author, David Oliver Relin, had no idea that he'd fabricated the story, nor that Mortenson had been embezzling money from the Central Asia Institute. A supporter of Mortenson’s humanitarian efforts, Relin was devastated to learn he had enabled the fraud, and later committed suicide.

29. A Whale of a Tale

Bob Dylan’s 2017 Nobel Prize for Literature win was already controversial, but criticism only intensified when reporters discovered that Dylan lifted much of his acceptance speech from the SparkNotes summary of Moby-Dick. Seriously.

30. Man’s Gotta Have a Code

Purists might have preferred if Dylan followed the example of Jean-Paul Sartre. The French existentialist caused monocles to drop in 1964 when he refused the Nobel Prize in Literature. Sartre declined all official awards as a matter of personal ethics, but many expected he would at least make an exception for the most prestigious prize in literature. Nope.

31. Beggars Can’t Be Choosers

A member of the Nobel Prize committee would later claim that Sartre wrote the committee in 1975, asking for his prize money. They denied the request.

32. In Good Company

Sartre remains one of only two people to voluntarily decline the Nobel Prize. The other was Vietnamese diplomat Le Duc Tho, who oversaw the ceasefire of the Vietnam War.

33. Ignoble Prize

Say what you will about Bob Dylan (or Sartre), but at least someone won the prize those years. In 2018, Jean-Claude Arnault, husband of Nobel board member Katarina Frostenson, was convicted of sexual assault. To make matters worse, during the trial, lawyers uncovered that Arnault and Frostensen had leaked the names of nominees in order to profit off betting.

Nearly half the board resigned in the aftermath, either in protest against Frostenson and Arnault, or because of their own implication in the scandal. With the board in disarray, they eventually waved a white flag. No one received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2018.

34. Two for One

To make up for lost time, the Nobel committee awarded two prizes for literature in 2019. They went to Olga Tokarczuk and Peter Handke.

35. Permanent Marker

A young poet named Ailey O’Toole was overjoyed when her poem, “Gun Metal” was nominated for the Pushcart Prize. She even went so far as to get lines from the poem tattooed on her arm. She made the mistake, however, of sharing a picture of the tattoo on Twitter, where it caught the attention of another poet named Rachel McKibbens—the actual author of those lines. Awkward...

36. Edited Out

Understandably outraged, McKibbens tweeted about O’Toole's plagiarism. It kicked off a social-media firestorm, as readers either joined McKibbens in indignation or reveled in the schadenfreude. The now-regrettably tattooed Ailey O’Toole disappeared from Twitter almost immediately, her book pulled from shelves, her Pushcart nomination rescinded, and her career finished before it ever really started.

37. Well, That Backfired

Social media outrage hasn’t worked out for everyone of course. Take Tomi Adeyemi, who took to Twitter to point out similarities between the cover of her book, Children of Blood and Bone, and one with a similar title by romance novelist Nora Roberts. Unfortunately for Adeyemi, Roberts had receipts. In a social media post of her own, Roberts pointed out that her book came out a whole year before Adeyemi’s.

To add insult to injury, she included the fact that she’d never even heard of Adeyemi. Adeyemi, faced with the evidence, apologized to Roberts.

38. Who Watches the Watchman?

Harper Lee’s novel To Kill a Mockingbird is one of the most beloved books in American literature. The sequel, Go Set a Watchman, is considerably more controversial. Written in the 1950s but published shortly before Lee’s 2016 death, many have speculated that Lee's publisher released Go Set a Watchman against her wishes.

39. Clean Bill of Health

That Lee would publish a sequel to her famous novel did seem suspicious: For decades, she maintained she would never publish another book. Eventually, the situation caused enough noise that the State of Alabama investigated the issue. While Lee’s health was failing, investigators found that she was of sound mind and happy with the publication.

40. You’ve Changed

Fans of Lee’s original novel were not as happy. Set 20 years after the events of To Kill a Mockingbird, Go Set a Watchman depicts a world—and a world view—drastically different from that of Lee’s earlier novel. One of the most jarring changes: Atticus Finch, the soft-spoken father and moral compass of To Kill a Mockingbird, was now a segregationist.

41. Ancient History

Authorship hoaxes are not just a phenomenon of the modern world. Perhaps the earliest literary scandal dates back to the 5th century CE. Around that time, a Christian theologian produced a work called the Corpus Areopagiticum. Identifying himself as “Dionysios,” the author claimed St. Paul himself converted him—in fact, he said he was literally the Dionysios mentioned in the bible.

42. Homework

While the theology contained in the Corpus Areopagiticum was influential, authorship of the text led to a debate that lasted more than 1,000 years. Thomas Aquinas himself weighed in on the subject. So did Martin Luther. By the 19th century, most scholars and theologians accepted that the author was not the convert of St. Paul. Scholars believe the author, “Pseudo-Dionysios,” was probably a Syrian pupil of the Neoplatonist Proclus.

Sources: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21