“Even in prosperous times, the living robbed the dead.” ―Jocelyn Murray, Khu: A Tale of Ancient Egypt

Sometimes that final resting place doesn’t turn out to be all that restful. Throughout history, graves have been robbed for numerous unseemly reasons ranging from cannibalism to black market dealings to mere grotesque boredom―and if you happened to die in North America, Ireland or the UK during the 18th and 19th centuries, there’s a good chance your corpse could rake in some serious dough being sold to surgeons and medical students for dissection. As the Halloween season slowly creeps upon us, here are some ghoulish facts about the gruesome world of grave robbing to ease you into the festive spirit.

Grave Robbing Facts

26. Real Gentlemanly...

At the height of the Enlightenment, only the bodies of executed criminals were permitted to be used for medical science. But with the number of executions in London averaging around 50 a year and a lack of refrigeration making preservation of specimens rather difficult, the demand far exceeded supply. As a result, medical students and anatomists took matters into their own hands, stealing corpses for their own use. This meant that some of the earliest 18th century grave robbers (or more specifically, body snatchers) in London actually belonged to the Gentleman class.

25. Nefariously Profitable

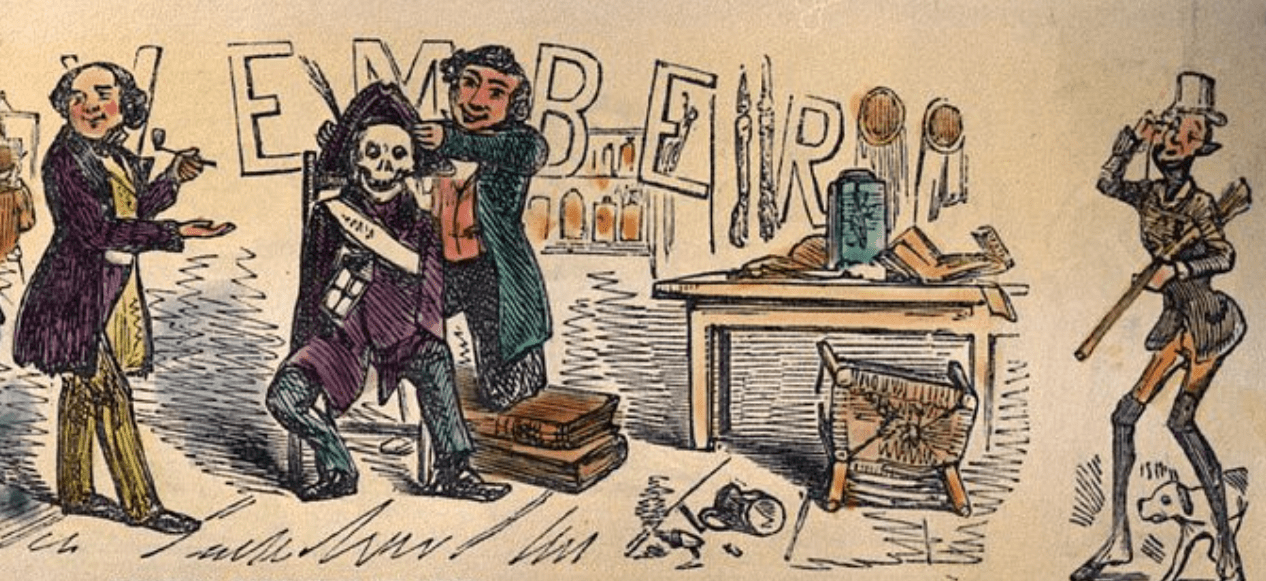

As the medical demand for cadavers grew in the early 19th century and anatomists grew more and more desperate, many of them turned to so-called “ressurectionists” or “ressurection-men”: thieves who made their living pilfering the grave sites of the deceased and selling their corpses to anatomy schools, no questions asked. Many of these deviants made a pretty decent living, and were so efficient and effective that they became indispensable to their benefactors.

24. Lying in Wait

Typically, a member of one of these gangs of grave robbers would loiter in a likely graveyard, waiting for a funeral. They might even join the mourners just to get a closer look at the newly dug grave and more effectively plot that night’s misdeeds.

23. Devious But Discreet

Body snatchers usually worked at night and as part of a gang. They preferred graves that were covered roughly to ensure their work went undetected.

22. Using Their Heads

Body snatchers rarely dug up the entire coffin; instead they would simply uncover the head end of the grave. The body would then be hoisted to the surface with ropes or a metal hook, head first. The clothes were thrown back into the coffin, the tunnel filled in, and the ground smoothed over so no one was the wiser.

21. Dear Diary...

It was rare that a grave robber would keep a diary of his work, but one who did was Joseph Naples, active in London from 1811 to 1832. Naples detailed a couple of foiled attempts in August 1812: “Separated to look out, the party met at night…Willson, M. & F. Bartholm, me, Jack and Hollis went to Isl[ingto]n. Could not succeed, the dogs flew at us, afterwards went to [St] Pancr[a]s, found a watch planted, came home.”

20. An Important Distinction

Though almost universally considered to be an abhorrent practice, actual laws forbidding body snatching were not quite as clear-cut at this time. Stealing from graves was very much illegal though, and so the common practice of returning the deceased's possessions to the coffin after removing the corpse created an important distinction between actual grave robbing and just plain old innocent body snatching.

19. I Predict a Riot

Even though there weren’t always legal repercussions for their actions, snatchers were still in danger of being attacked by citizens who disapproved of both body snatching and medical dissection during so-called “resurrection riots.”

18. No, Seriously

Notable among these ressurection riots was the New York Doctor’s Riot in 1788. Anatomists and students in New York Hospital had been digging up graves for study and dissection, which people generally turned a blind eye too as long as the grave robbing was restricted to the African American or poor graveyards. But when news broke of a white woman’s body having been stolen from Trinity Churchyard, a group of men stormed the hospital’s anatomy room and a bloody riot ensued. Doctors and students were taken to jail for their own protection and only the intervention of the state militia ended the carnage, which left between six and 20 people dead.

17. One of Many

The New York Doctors Riot was just one of many riots that plagued the United States in the 18th and 19th centuries. At least 17 such incidents were recorded between 1765 and 1854 in New Haven, Baltimore, Cleveland and Philadelphia.

16. A Plague on Both Your Houses

It seems William Shakespeare was all too aware of the potential dangers awaiting his (surprisingly shallow) grave. His grave carries this warning: “Good friend, for Jesus’ sake forbear, / To dig the dust enclosed here. / Blessed be the man that spares these stones, / And cursed be he that moves my bones.”

15. Bard’s Bones Befouled!

And as it turned out, Shakespeare had reason to be wary. A story often brushed off as pure fiction—that 18th-century grave robbers stole Shakespeare’s skull—was concluded by a group of archaeologists in 2016 to in fact be more than likely true. They found that the Bard’s head appeared to be missing, and that the skull was likely stolen by trophy hunters.

14. Money Still Talks

Grave robbing is still happening today on some level. In May 2015, the Chinese regime’s Public Security Ministry claimed that 175 people had been arrested in six provinces for raiding tombs, making it the single largest operation of its kind for decades. These suspected criminals were accused of stealing and trafficking over 1,000 grave relics worth about $80 million.

13. On The Lighter Side...

Necrolestes patagonensis is a small, extinct, mole-like mammal that lived through the mass extinction of the dinosaurs. Pretty impressive. What’s it doing on this list, you ask? Its name translates to “grave robber,” referring to its subterranean lifestyle.

12. The Vulnerable Poor

Body snatchers tended to frequent graveyards for the poor, as they were unlikely to be guarded. In poor districts, coffins were often buried in stacks, and not very deeply. Still, ordinary folks found ways to at least try to protect their dead. They would delay burial, mix straw with the earth to deter the snatchers' shovels, or simply guard the gravesides themselves.

11. Just a Little Longer...

Relatives would often mount a night watch over a fresh grave for 2 or 3 weeks, after which the body would have decomposed sufficiently to be useless for dissection.

10. Corpses Upon Corpses

If you were wealthy and you wanted to be absolutely certain your corpse would remain in its original packaging, undisturbed and unsold, you could always ask your heirs to arm your coffin with a torpedo. While most body snatching deterrents simply involved shielding the dead body from the outside world with a barrier of some kind, the 19th century saw a more explosive solution hit the markets. Coffin guns and “grave torpedos” might sit on the lid of a buried coffin and fire lead balls at intruders, or they might take the form of an explosive shell packed with gunpowder. These devices did kill some hopeful resurrectionists, warning others to think twice about where they stick their shovels.

9. I’m Still Here!

As more and more of these deterrents came about and graves became more secure, the fear of being buried alive grew among the more morbidly anxious sorts. If someone had been buried prematurely (which really did happen), these grave-protection devices only made it more difficult to rescue them. This led to the invention of a number of features and coffin alarm systems that could be used if one were to find themselves entombed with a nasty case of the not-quite-dead-yets. One of these features was a vault that could be opened from the inside by turning a wheel.

8. Fun’s Over, Guys

Willy-nilly grave robbing couldn’t go on forever. The combination of body snatchings, murder, and the resurrection riots led to the enactment of the Anatomy Act in Britain in 1832 and similar acts in US in subsequent years. These acts aimed to deter snatching by making more bodies available for medical purposes, which was initially achieved by sanctioning the delivery of unclaimed bodies (mainly of the poor and the ill) to anatomy schools.

7. Tut Tut

Ancient Egyptian tombs are no strangers to grave robbery. Most of the tombs in Egypt's Valley of the Kings were robbed within 100 years of their sealing, including the tomb of the famous King Tutankhamen, which had been raided twice prior to its discovery in 1922.

6. Charlie’s Last Laugh

Instigating one of the most spectacularly unsuccessful body snatchings in history, screen legend Charlie Chaplin's body was dug up from its resting place in Switzerland in March 1978, two months after his death. Charlie's widow Oona received a ransom note asking for $600,000 for the safe return of the body, which she outright refused to pay, saying "Charlie would have thought it rather ridiculous." Two mechanics from Eastern Europe, Roman Wardas and Gantscho Ganev, eventually led police to the cornfield where they had temporarily buried him, and were arrested in May of that year for grave robbing and attempted extortion. Chaplin's body was reburied in a concrete grave as a deterrent against future meddling.

5. Honest Abe’s Grave Prevails

In November 1876, four counterfeiters led by small-time crime boss Big Jim Kennally broke into Oak Ridge Cemetery in Springfield, Illinois to steal Abraham Lincoln’s body from his sarcophagus, which was secured with only a single padlock. Their demands: $200,000 in ransom and a full pardon for Benjamin Boyd, who was doing 10 years in prison at the time. Simple enough, right? Well, the "experienced grave robber" they hired for help with the heist turned out to be a paid informant of the secret service. They didn’t get very far.

4. Hare and Burke

Notorious among the ressurectionists in the UK were William Hare and William Burke, who saw a suspiciously large upswing in business over a ten month period in 1828. As it happens, they had taken to murdering people themselves and selling the fresh corpses. They committed a total of 16 murders during this time, though only Burke was charged and eventually hanged for the crimes.

3. Anyone Up For Some Burking?

The public was incensed upon learning that Burke and Hare killed their subjects, and from then on the act of killing people to obtain biological specimens for anatomists was known as Burking.

2. Irony

Funnily enough, Burke’s body was turned over to an anatomist in Edinburgh for public dissection, and his death mask, skeleton, and other items such as a leather wallet made from his tanned skin are now displayed at the Royal College of Surgeon’s museum.

1. Over My Dead Body

Around Burke and Hare's time, many precautions were taken by people to protect their dead, such as hiring watchmen with guns and guard dogs or building a mortsafe, an iron cage built over the grave.

Sources: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17