"I was the conductor of the Underground Railroad for eight years, and I can say what most conductors can't say; I never ran my train off the track and I never lost a passenger." —Harriet Tubman

When we learn about the Underground Railroad in school, we get a vague idea of the brave actions of the people who worked to lead slaves to freedom after years of horrifying treatment by their masters. Maybe we learn a few names or stories, but it’s nearly impossible to capture the breadth of the effort that was put into the operation of the Underground Railroad by those who helped to make it happen. There’s no more noble cause than trying to help get slaves away from those who wanted to oppress them and send them onto a better life where they had their freedom. There was so much that went into ensuring the system was successful, along with many players who made it possible. Here are 42 extraordinary facts about the Underground Railroad.

Underground Railroad Facts

42. The Root of the Name

First and foremost, where did the name come from? Underground was just the term used to mean that it was a secret movement. At the time, the rails were a new and evolving way of transportation. Railroad terms were also commonly used when talking about the people involved in the Underground Railroad. What started as a simple and functional term came to define the incredible movement.

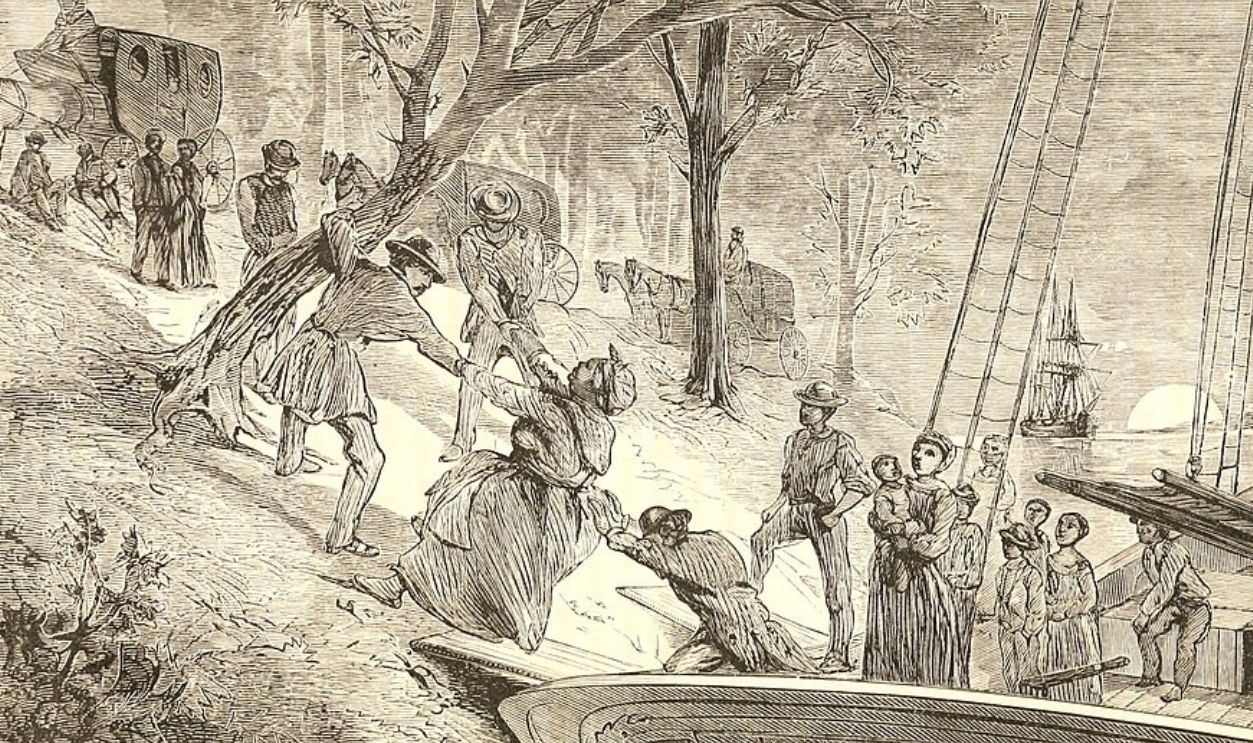

Charles T. Webber, Wikimedia Commons

Charles T. Webber, Wikimedia Commons

41. Early On

There were a couple of instances in the 1800s where the secret Underground Railroad was first referenced in the media. One Kentucky slave owner blamed what he referred to as an “underground railroad” for the loss of his slave, Tice Davids, in 1831. Davids had fled to Ohio. Eight years later, a newspaper in Washington told of a slave who, under duress, admitted that he was going to use an “underground railroad” to flee to Boston.

40. All Aboard!

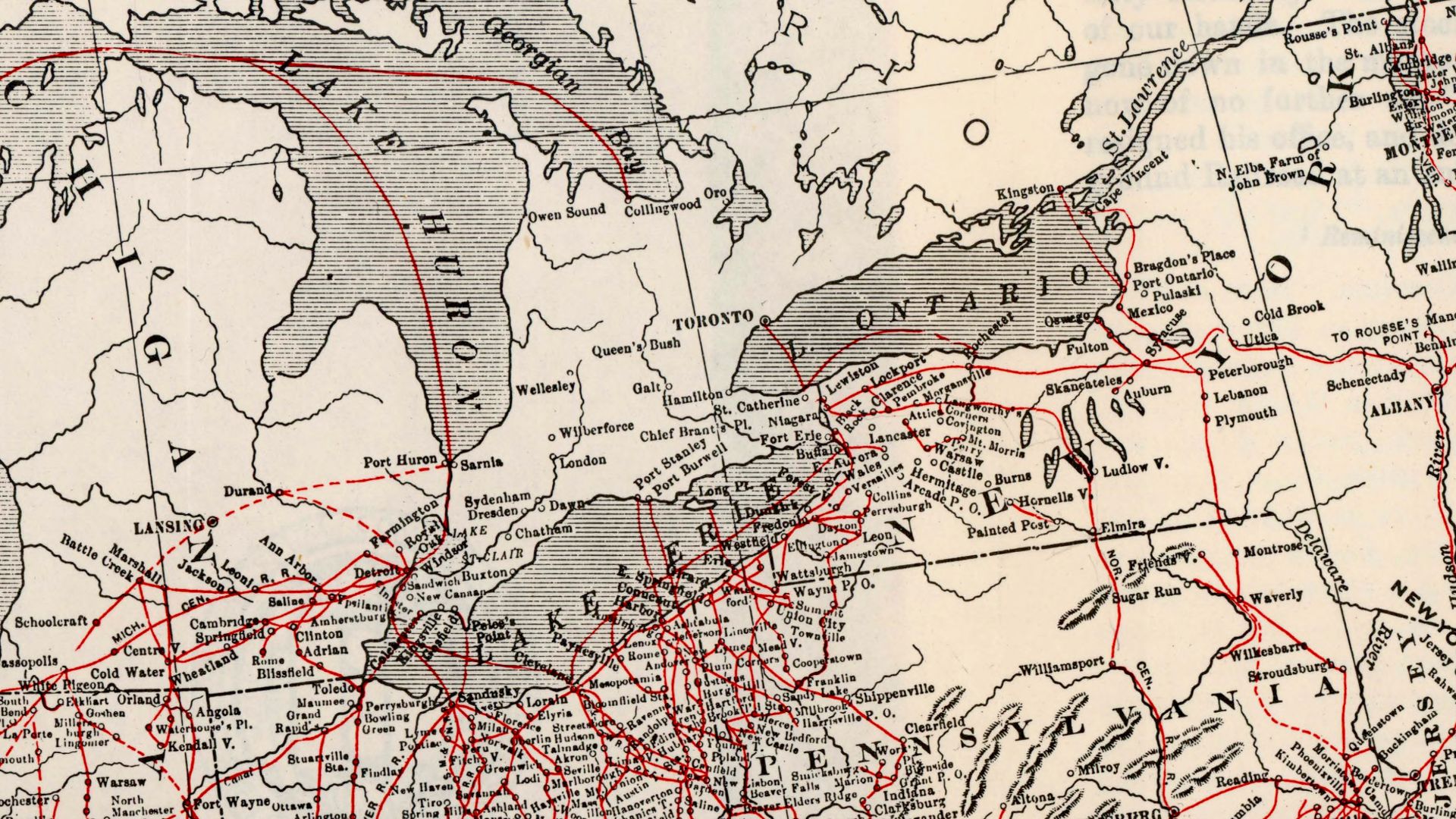

The routes used by the slaves weren’t how we expect a train to run today—on time schedules, on certain paths, etc. A number of different routes took shape throughout the Underground Railroad’s time, with destinations like northern US states, Mexico and the Caribbean. While we generally think of Canada as the ultimate destination on the Underground Railroad, routes to Canada only really came about after 1850.

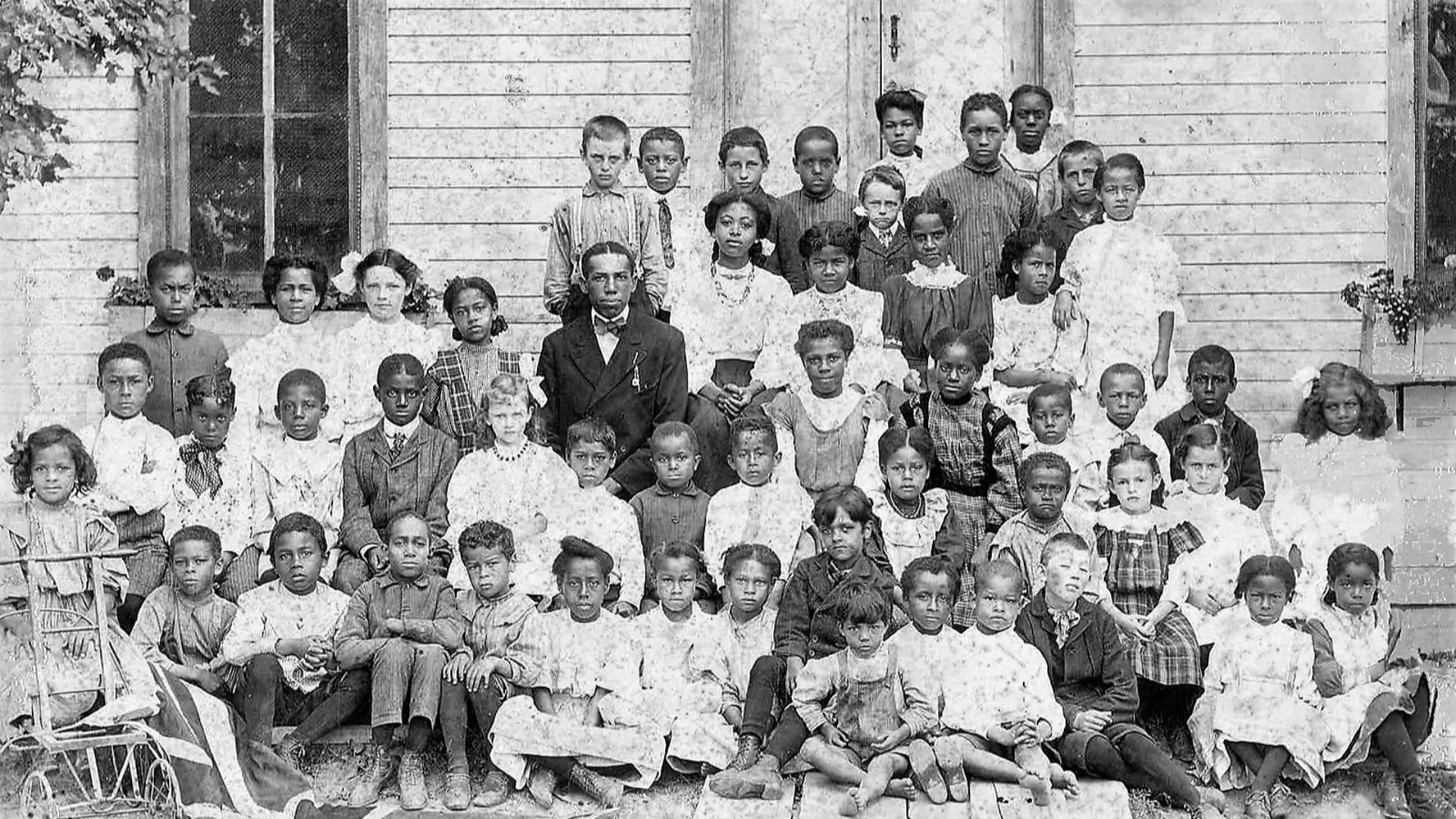

39. True North, Strong and Free

In Canada, escaped slaves were automatically free. They were free to live where they pleased, be a member of a jury during a trial, and to run for public office, among other freedoms. Some of the operators of the Underground Railroad who established themselves in Canada spent their time helping the newly-free slaves.

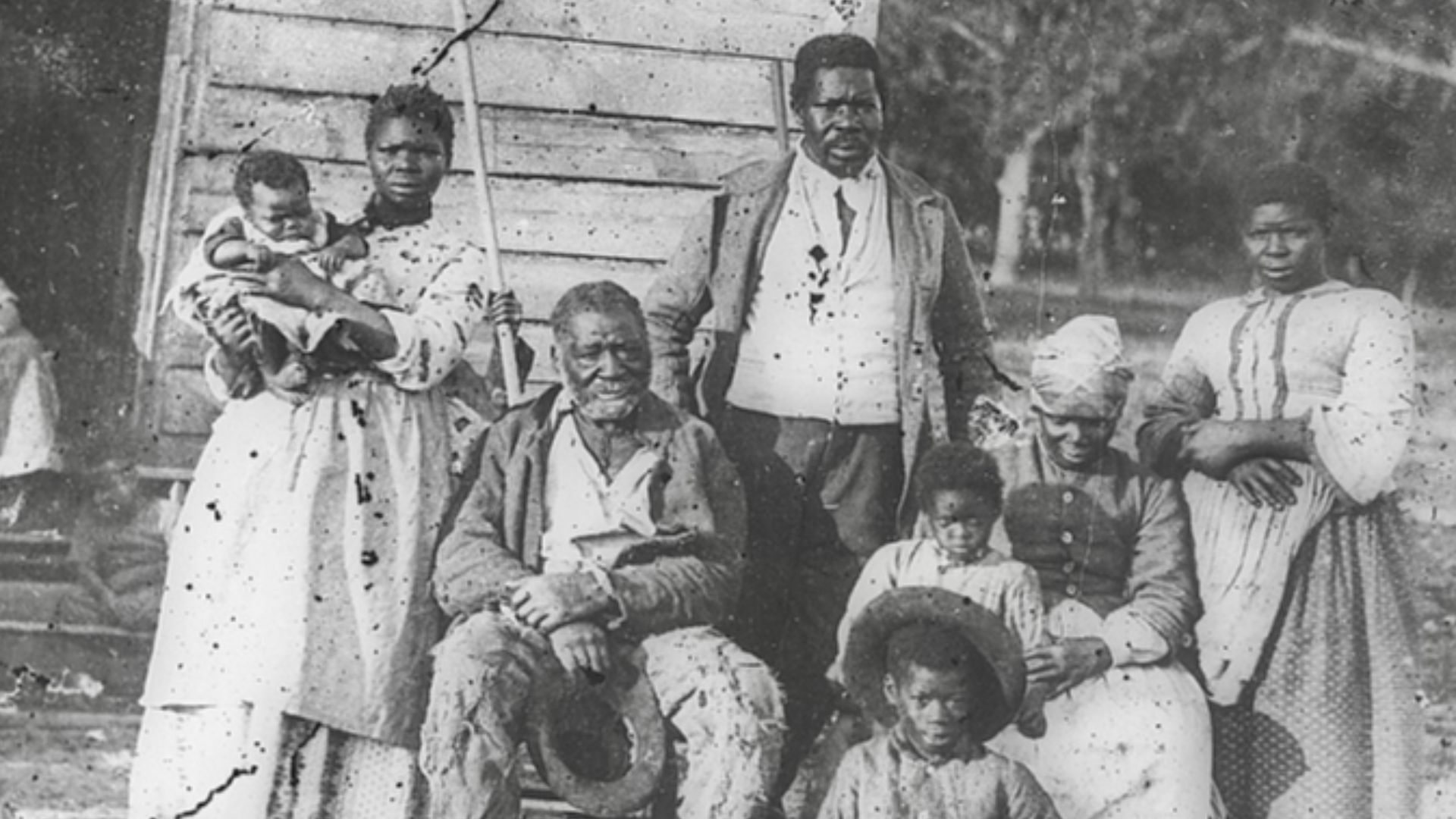

Buxton National Historic Site, Wikimedia Commons

Buxton National Historic Site, Wikimedia Commons

38. No Easy Road

It wasn’t always great in Canada, though, as many Europeans were also heading to Canada around the same time and also seeking work. Discrimination was still rampant, despite slavery being abolished. In 1785, Saint John, New Brunswick actually amended its charter to state that black people weren’t allowed to practice trades, sell goods or fish in the harbor. It wasn’t until 1870 that those terms were reversed. On the opposite side of the country, Vancouver Island in British Columbia welcomed those in the black community, hoping to unite the population and outnumber the political forces who wanted to unify Canada with the US.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

37. Almost a Century Running

The Underground Railroad unofficially began back in the 1780s and didn’t stop running for roughly 80 years—when the Emancipation Proclamation was brought into law in 1863 by President Abraham Lincoln. The term itself started becoming common in the 1830s, roughly halfway through movement.

Francis Bicknell Carpenter, Wikimedia Commons

Francis Bicknell Carpenter, Wikimedia Commons

36. Facing the Backlash

During the 1850s, the Underground Railroad hit its peak. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 made it almost impossible for slaves to get away from their masters. Under this act, any slave who escaped could still be brought back to his or her master, despite being in a free state—which is why many started going even further north, to Canada. Anyone who was caught helping a slave or just offering shelter to an escaped slave could face the judicial system and wind up with a jail term of up to six months, or a $1,000 fine.

Eastman Johnson, Wikimedia Commons

Eastman Johnson, Wikimedia Commons

35. Guilty of Nothing

The Fugitive Slave Act was pretty controversial—all a slave hunter had to do was go before a judge and declare a person of color, regardless of whether or not they were actually free, an escapee. There was an assumption at that time that all persons of color were escapees or runaways. They didn’t even have a chance to defend themselves in a court of law, either. A year after the Emancipation Proclamation came into legislation, the Fugitive Slave Act was repealed.

David Hunter Strother, Wikimedia Commons

David Hunter Strother, Wikimedia Commons

34. End of the Line

The last person believed to be caught under the Fugitive Slave Act was Lucy Bagbe. She had escaped what is now West Virginia and made it to Cleveland, Ohio. However, her former master managed to track her down, bring her back, and punish her for escaping. Tragically, abolitionists tried to fight for her freedom to no avail. She was freed once more when Union soldiers occupied the estate where her owner lived. In 1863, Cleveland held a Grand Jubilee in her honor.

History's most fascinating stories and darkest secrets, delivered to your inbox daily.

33. Taking Advantage of the System

Slave hunters were even known to capture people of color who had never been a slave and who had been born free. They especially targetted children, selling them into slavery. Politicians in the south exaggerated the number of slaves they had, and judges were often bribed with a higher payout if they ruled in favor of a colored person being declared as a slave.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

32. Frederick Douglass: Fugitive Slave

One of the more recognizable names that came out of the Fugitive Slave Act era was Frederick Douglass, who was a fugitive slave himself. He was one of the more prominent leaders of the anti-slavery cause and went on to be a civil rights leader as well. He recruited black soldiers during the Civil War, was an advocate of women’s rights, and even met with President Lincoln.

George Kendall Warren, Wikimedia Commons

George Kendall Warren, Wikimedia Commons

31. Leading a Better Life

Douglass taught himself how to read and write, later publishing three autobiographies, including The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass in 1845, as well as having his own newspaper. His Rochester, NY home was the last stop for slaves escaping to Canada for a better life and he frequently had upwards of 11 escapees in his home at one time.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

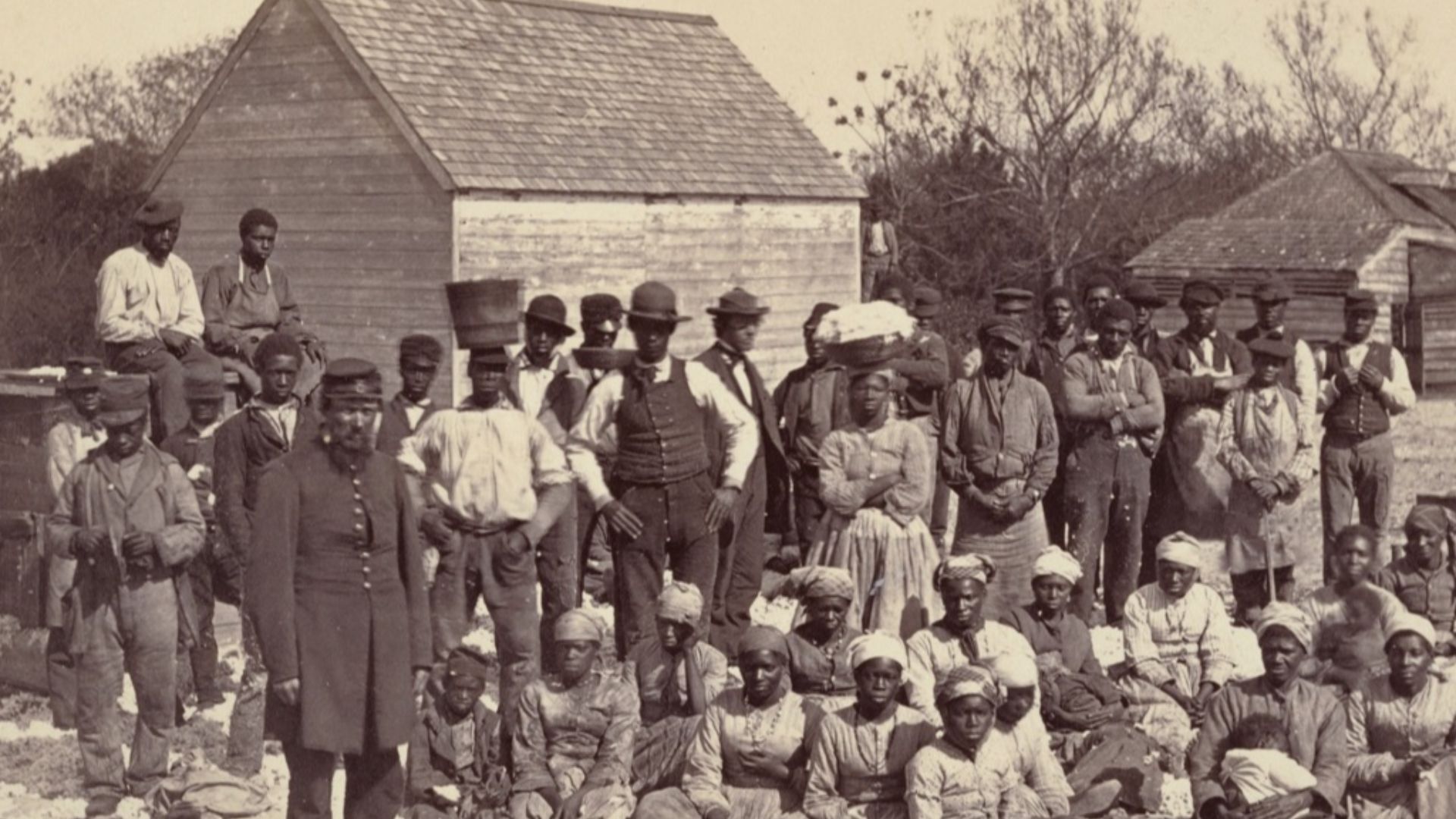

30. Fighting for More Than Just Country

During the Civil War, both enslaved and free black men fought for the Union Army. After the Union claimed victory in December 1865, slavery was abolished under the Thirteenth Amendment. Many slaves who had escaped to Canada and elsewhere before this time actually returned back to the US in what was essentially a reverse Underground Railroad situation.

Photographer, Henry P. Moore (1833-1911), Wikimedia Commons

Photographer, Henry P. Moore (1833-1911), Wikimedia Commons

29. Fighting Fire With Fire

States in the northern US tried to fight the Fugitive Slave Act with something of their own, called Personal Liberty Laws. Unfortunately, this would be to no avail. The Supreme Court knocked them down in 1842.

Photo by Mr. Kjetil Ree., Wikimedia Commons

Photo by Mr. Kjetil Ree., Wikimedia Commons

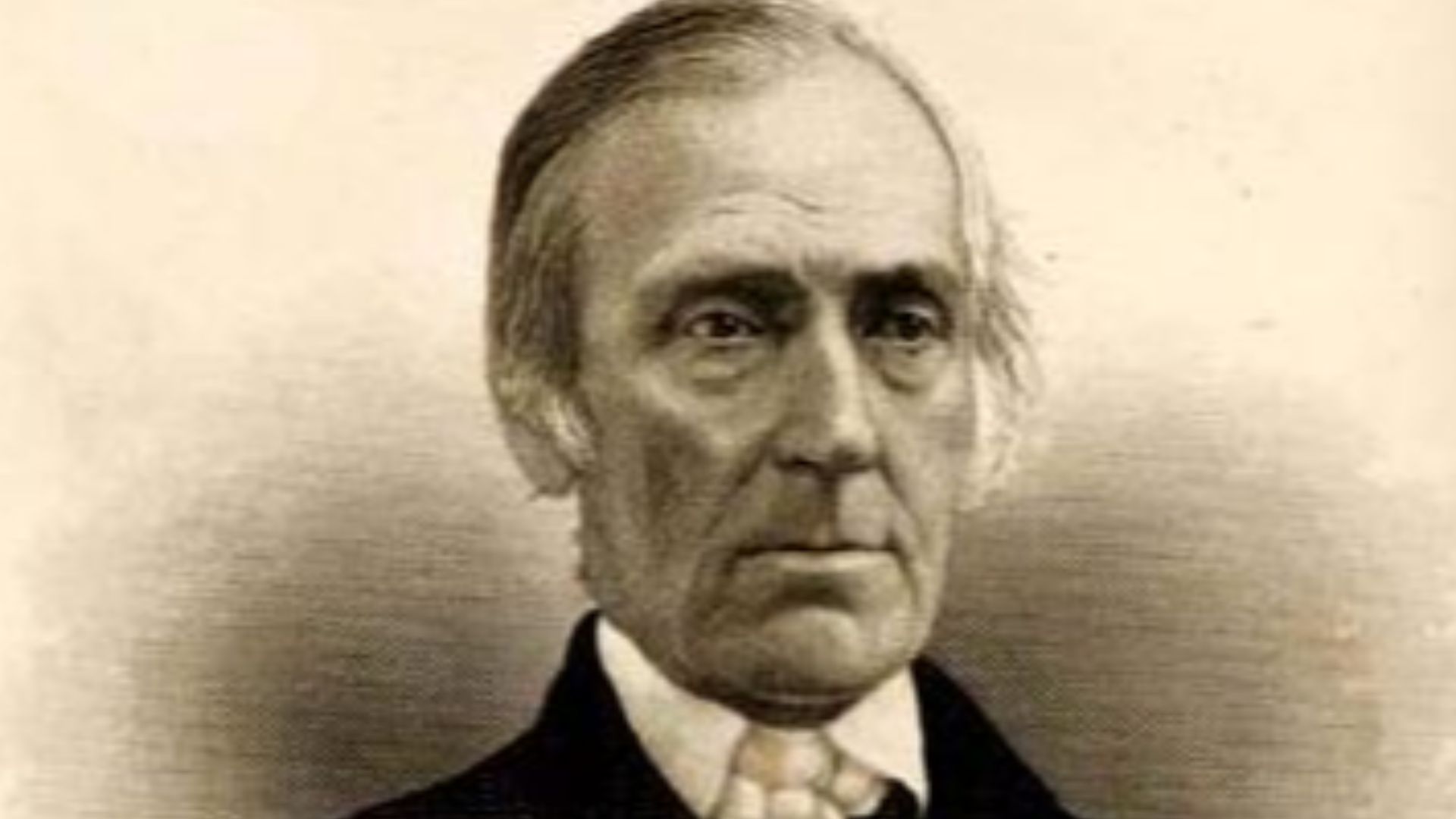

28. Levi Coffin: Mr. President

Another important name to note is Levi Coffin. He was known as the Underground Railroad’s unofficial president, with his own home being considered as the Grand Station. So many slaves passed through his home, which helped give him this reputation. His wealth as a businessman helped him aid the slaves seeking freedom.

27. Making a Name for Himself

Coffin had begun helping slaves when he was only 15 years old. He learned where slaves were hiding and helped them along their way, no matter where he lived. He was originally a North Carolina Quaker, but eventually moved to Indiana and Ohio. At some point, he didn’t even need to seek out slaves anymore, as they would manage to find him on their own.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

26. Random Acts of Kindness

Unlikely places became hiding spots for slaves. Compartments hidden inside cupboards, cellars, basements and passages were all spaces used to hide slaves trying to get away safely. The people who helped the slaves usually did so spontaneously, and race, age, or gender had no bearing. Men, women, children, people of color, Quakers and Methodists alike all helped to ensure safety and shelter for those who sought it.

25. No, They Aren’t a Brand of Cereal

What is a Quaker, you may find yourself asking? Simply put, it was a religion. Also known as the Religious Society of Friends, they were widely known as being pacifists and believed in equal rights amongst men, women and persons of any color. George Fox founded the Quaker movement in England in the 17th century, with it coming across to America somewhere in the mid-1650s.

attributed to Peter Lely, Wikimedia Commons

attributed to Peter Lely, Wikimedia Commons

24. Fighting for Everyone’s Rights

Originally, the Quakers fought for rights for Native Americans, but then found themselves helping slaves. Quakers in Philadelphia were banned from owning slaves as of 1758, and all Quakers were banned from owning slaves roughly 20 years after that. Famous Quakers include former US Presidents Herbert Hoover and Richard Nixon, as well as John Cadbury (founder of the chocolate company) and Johns Hopkins.

Bain via Clinedinst, Wikimedia Commons

Bain via Clinedinst, Wikimedia Commons

23. The Less Information, the Better

The people who helped support the escaping slaves wouldn’t know the entire routes, either—they would only know small portions of it. This would help keep anyone from trying to infiltrate the Underground Railroad and finding out too much valuable information which could put slaves and those helping them in danger.

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

22. Two Sides to the Cause

The practice of bounty hunting actually came about to track down escaped slaves, but the anti-slavery movement had their own response: vigilance committees. The people in these committees helped protect slaves in New York in 1835 and Philadelphia in 1838. They went beyond just protection as well—they also starting guiding slaves on their route to freedom.

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

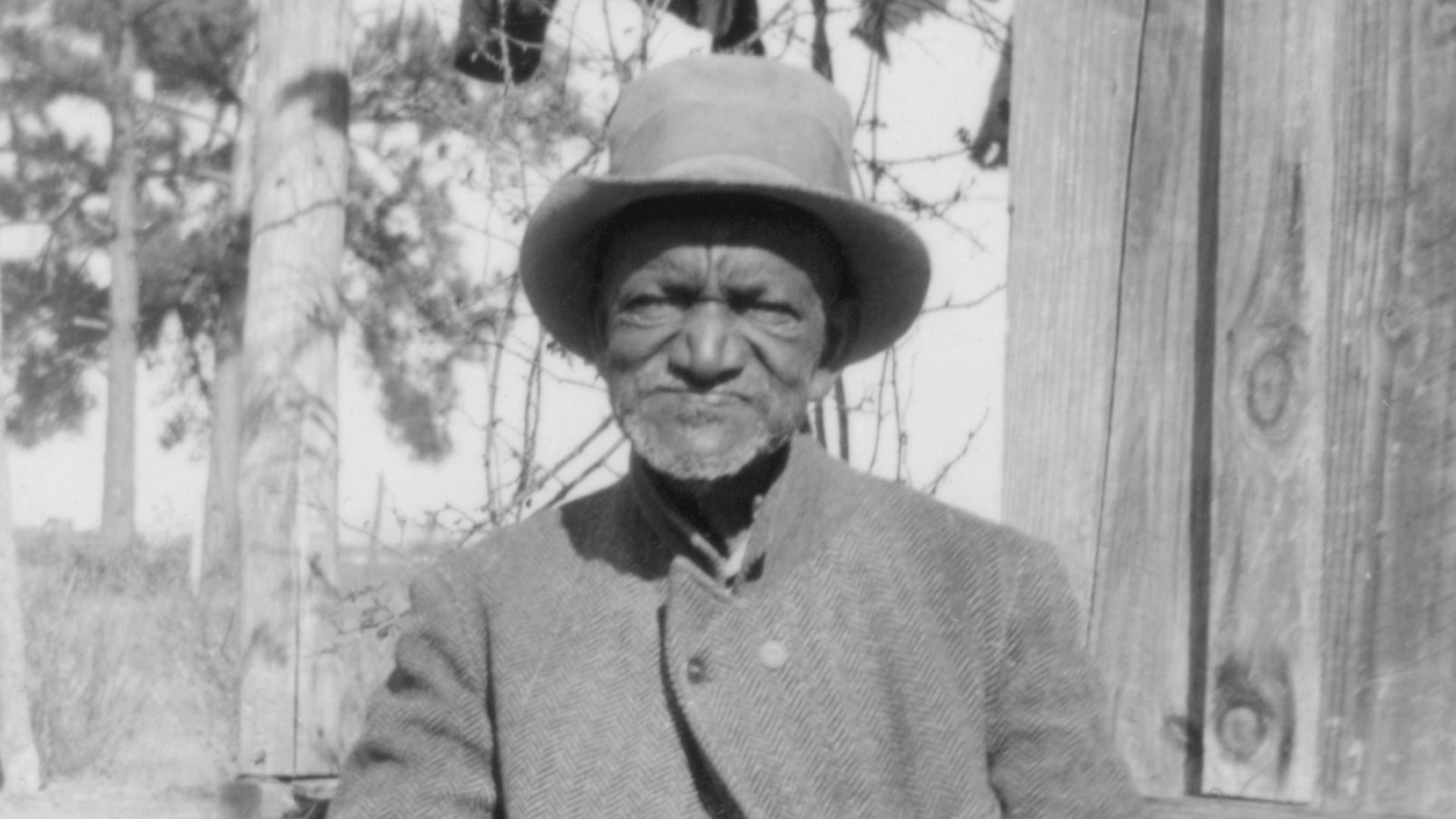

21. Elijah Anderson: Man of Disguise

Elijah Anderson, though a black man, easily passed as white because his skin tone was so light. He often posed as a slave owner in efforts to get slaves to freedom. Rumor has it that he was able to get between 20 and 30 slaves together at one time to free them, with some trips even taking him as far as Coffin’s home in Newport from Indiana. Before being sent to jail in Kentucky for “enticing slaves to run away,” he was able to free some 800 more slaves. He was found dead in his jail cell on what some reports say was the day he was to be released.

20. See Them for Yourself

The US Department of the Interior National Park Service actually lists all the places that were used as stations during the time the Underground Railroad was in full swing. 23 states in total, including Florida, Iowa, New York, Wisconsin, Indiana, Colorado and Kentucky, to name a few, are home to either one, a few or even upwards of 13 stations (namely, Ohio), where escaping slaves could stay on their journeys.

Jeffrey Beall, Wikimedia Commons

Jeffrey Beall, Wikimedia Commons

19. The Path Was Hard

More often than not, slaves escaped at night to the next station on foot, through rivers, swamps and mountains. Larger cities like Philadelphia, New York and Boston had committees who raised funds for shelter and even temporary jobs for the escapees.

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

18. Sojourner Truth: a Free Woman

One remarkable woman who dedicated her life to helping slaves was Sojourner Truth. Born Isabella Baumfree, she escaped with her baby in 1826 and became an advocate for the end of slavery, especially in Ohio, where she was based out of. Not only fighting for the rights of slaves, she also petitioned for women’s rights, even speaking at Ohio’s Women’s Rights Convention in 1851 and delivering her speech, “I ain’t a woman.”

Randall Studio, Wikimedia Commons

Randall Studio, Wikimedia Commons

17. The Who’s Who

The people who helped—station masters, operators, conductors, agents and stockholders, to name a few—had secret codes to communicate with each other, and the slaves had their own songs.

various gov't employees, Wikimedia Commons

various gov't employees, Wikimedia Commons

16. Learn the Lingo

The code words used are pretty interesting, too. Here’s some for you: agents helped to plot courses, baggage were the fugitive slaves, flying bondsmen indicated how many slaves were escaping while parcels indicated how many slaves were expected, stockholders donated money, clothing and food, and a station master was the keeper or owner of a house. There were a few terms used for Canada itself: Canaan, heaven and promised land. Preachers were leaders and speakers of the Underground Railroad, while one famous name, Harriet Tubman, had the codename of Moses. On the darker side, a patter roller was someone who had been hired to recapture the slaves.

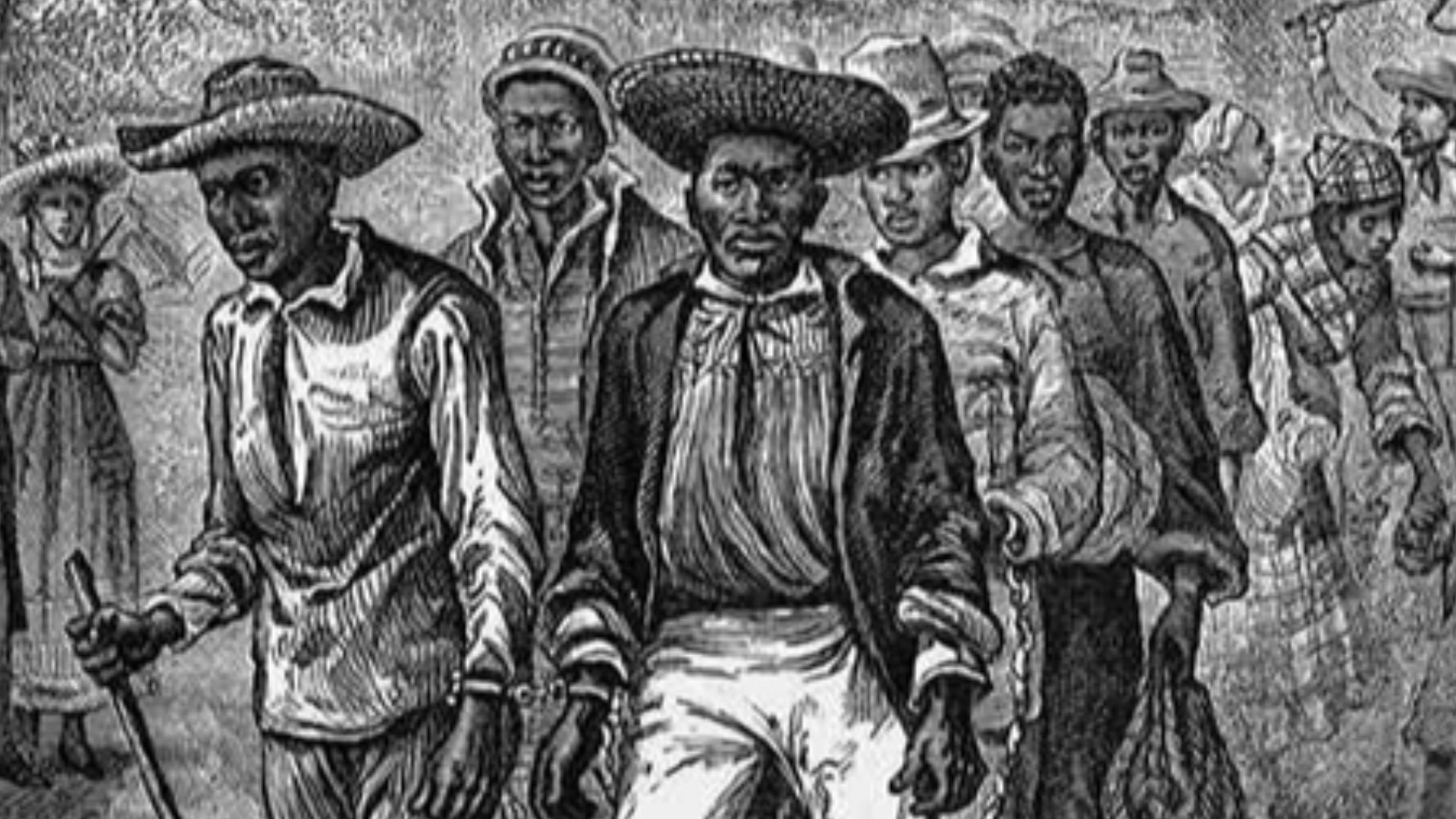

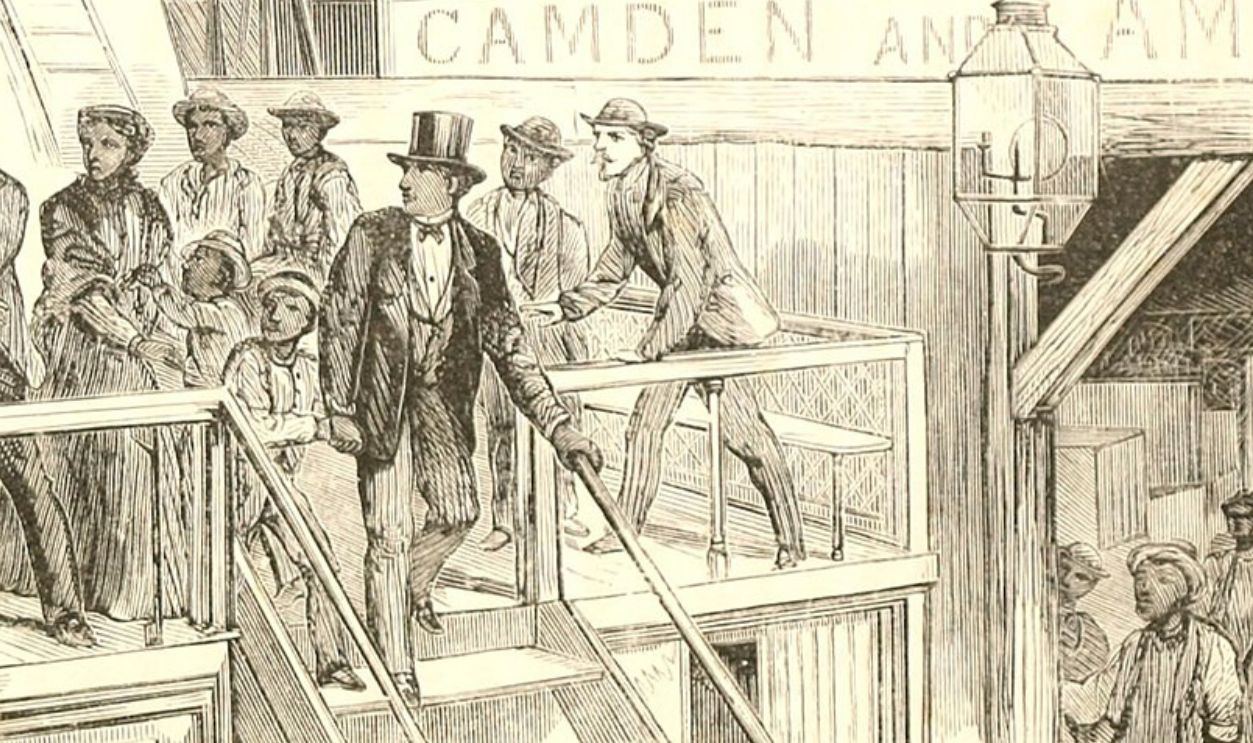

Gibson, James F., 1828-, photographer; Barnard & Gibson, copyright claimant, Wikimedia Commons

Gibson, James F., 1828-, photographer; Barnard & Gibson, copyright claimant, Wikimedia Commons

15. Singing for Freedom

African slaves originally used their songs to help make their days go by using a rhythm for their work, but turned them into coded songs while attempting to escape slavery. They would often give directions for escaping or where to meet. Those were known as signal songs and map songs, respectively. Keep in mind that slaves weren’t often taught how to read or write, so all that many of them had were words and song.

14. You Know How They Go

Some of the famous songs that came out of this time were “Wade in the Water,” “Steal Away,” “Sweet Chariot” and “Follow the Drinking Gourd.” There were also a couple of unnamed songs that Tubman sang to either let the slaves know whether or not it was safe to come out.

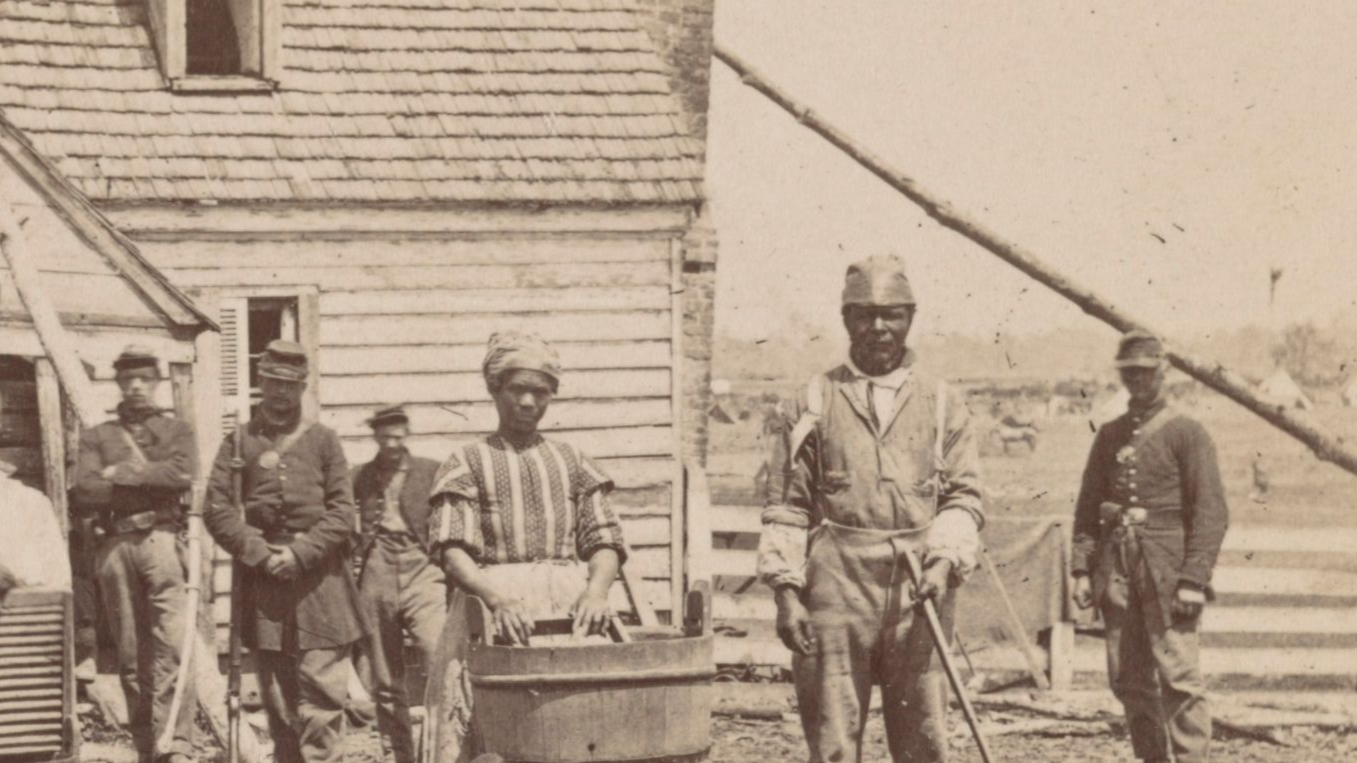

Timothy H. O'Sullivan, Wikimedia Commons

Timothy H. O'Sullivan, Wikimedia Commons

13. Freedom for Thousands

During its lifetime, an estimated 100,000 slaves were freed by using the Underground Railroad. A lot of those slaves came from Southern states that had borders with Kentucky, Virginia and Maryland, all of which were free states. Not very many were able to escape from the Deep South states.

James Michael Newell, Wikimedia Commons

James Michael Newell, Wikimedia Commons

12. Can’t Please Everyone

Someone who wasn’t a fan of abolishing slavery? George Washington. In 1786, he said that a “society of Quakers, formed for such purposes” helped one of his slaves get away. At that time, there was an early version of the Underground Railroad system working to help slaves get away from their masters.

Gilbert Stuart, Wikimedia Commons

Gilbert Stuart, Wikimedia Commons

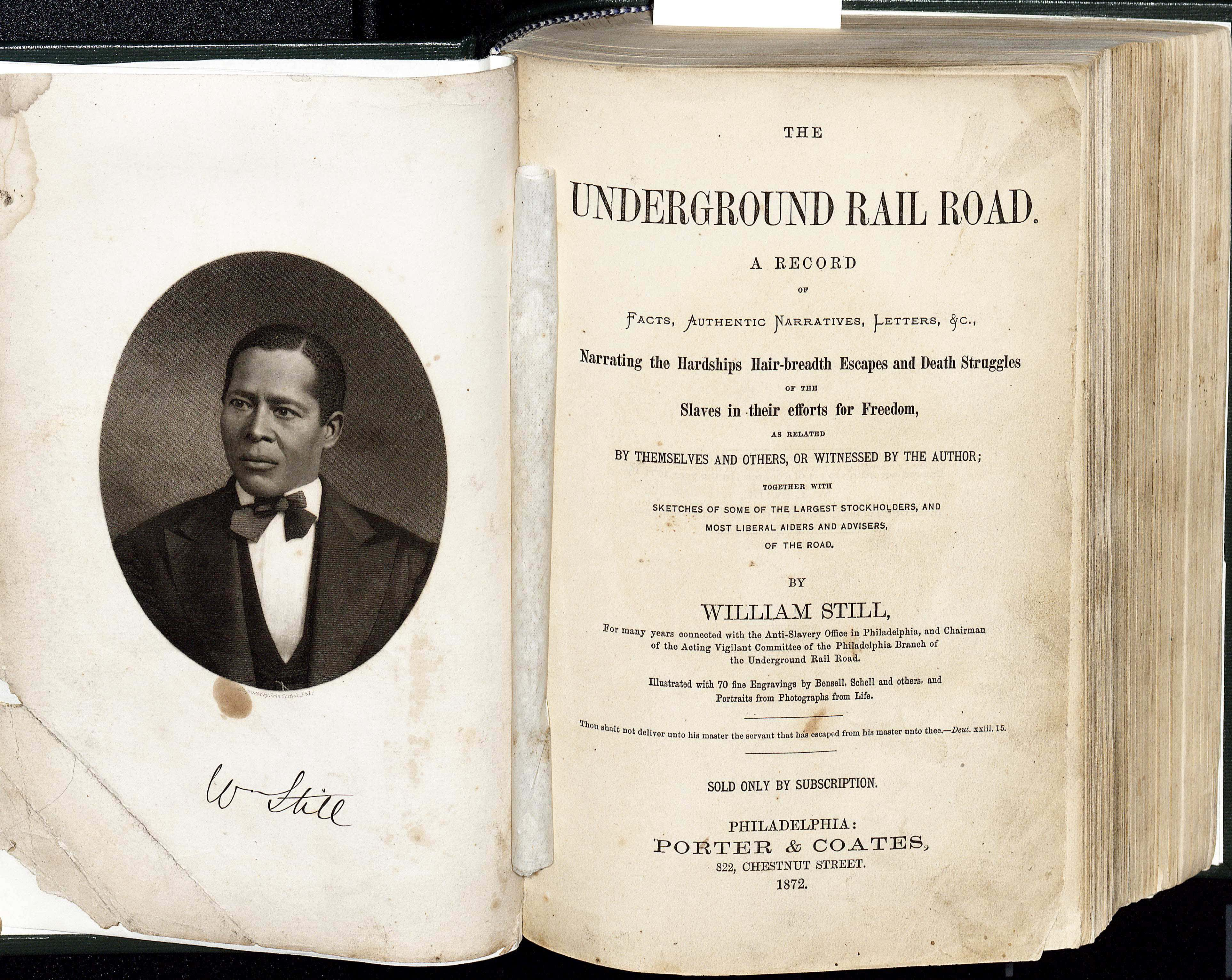

11. William Still: the Father

William Still was an incredibly important figure in the Underground Railroad. He was also known as the “Father of the Underground Railroad,” and helped hundreds of slaves gain freedom. At times he hid slaves in his own home, even helping upwards of 60 slaves escape in one month.

UnknownUnknown , Wikimedia Commons

UnknownUnknown , Wikimedia Commons

10. Keeping Them Safe...

William Still kept documentation about each person he had helped, which included small biographies. He made sure to use the metaphors as previously mentioned, such as “I have sent via at two o'clock four large hams and two small hams.” This would have indicated four adults and two children were sent to Philadelphia from Harrisburg, and the word “via” indicating through Reading, Pennsylvania. If any authorities intercepted the message, they would have gone to the wrong station.

Strand Studio, Wikimedia Commons

Strand Studio, Wikimedia Commons

9. And Keeping Their Stories Alive

What’s more is that Still often kept in touch with those slaves he helped escape to freedom. He acted as the go-between between the escapees and the people they left behind. He published a book in 1872, The Underground Railroad: Narratives and First-Hand Accounts, which details everything he experienced, which helps us now understand all the things that made the Underground Railroad function, and gives us much of the information we now have on the Railroad.

8. Tell Them Lies, Tell Them Sweet Little Lies

Slave owners in the South attempted to prevent their slaves from escaping by feeding them lies. They claimed the Detroit River was over 3,000 miles across and that those who opposed slavery were actually cannibals.

Michael Barera, Wikimedia Commons

Michael Barera, Wikimedia Commons

7. The Groups Who Aided

Way back in Pennsylvania in 1688, German Quakers rejected slavery as a matter of religion. Quakers were joined by other groups like the Mennonites, Dunkers and Shakers in aiding those seeking to escape slavery.

After: Egbert van Heemskerck I Print made by: Carel Allard (also publisher), Wikimedia Commons

After: Egbert van Heemskerck I Print made by: Carel Allard (also publisher), Wikimedia Commons

6. An Alliance With the Native Americans

Towards the beginning of the 18th century, it was actually Native Americans who helped slaves escape. One example being the Tuscaroras, who formed a community with the black Americans as part of their war against the colony of North Carolina. The Tuscaroras joined with the Five Nations, under Iroquois Confederacy, which was based in New York. When the Americans gained independence, the escapees were able to essentially create new identities through the Iroquois system.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

5. Radical Faction

John Brown was an abolitionist and conductor on the Underground Railroad who preferred using more guerilla-style methods to do his part. In fact, he's most famous for his own demise: he led a raid on Harper's Ferry as part of a plan to lead an army into the south and free slaves by gunpoint. However, his men failed, and Brown was tragically executed for treason in 1859 by way of the gallows.

Augustus Washington, Wikimedia Commons

Augustus Washington, Wikimedia Commons

4. Quilting for Escapees

There’s an idea that came about in recent times that quilts were used as a means of signaling routes and assistance to slaves, however, there has been a dispute over it. Those who believe in the quilt theory say that there were 10 different patterns used depending on the meaning, as well as for either signaling an escape or to specify directions. There have been a few quilt historians and Underground Railroad historians who say they have never seen evidence of this theory, so it’s hard to say if it truly was part of the codes used.

Downtowngal, Wikimedia Commons

Downtowngal, Wikimedia Commons

3. You Can’t Live Here

Despite the fact that there were states that didn’t approve of slavery, there were those who still didn’t want free black people to make their borders their home. Indiana, for example, actually passed a constitutional amendment stating that free black people weren’t allowed to settle there.

Momoneymoproblemz, Wikimedia Commons

Momoneymoproblemz, Wikimedia Commons

2. Harriet Tubman: the Moses of her People

One of the biggest names associated with the Underground Railroad is Harriet Tubman. Born a slave with the name Araminta Ross, Tubman became her married name and Harriet became her chosen name when she escaped slavery in 1849. She and two brothers escaped a Maryland plantation, though they went back after just two weeks. She then left on her own, but would keep going back to help her family members and others enslaved at the plantation. She said, “there are two things I had a right to—liberty or death. If I could not have one, I would have the other for no man should take me alive.”

Photographer: Horatio Seymour Squyer, 1848 - 18 Dec 1905, Wikimedia Commons

Photographer: Horatio Seymour Squyer, 1848 - 18 Dec 1905, Wikimedia Commons

1. An Incredible Woman

On the third attempt to free more slaves, she tried convincing her husband to leave. Unfortunately, he had remarried and refused to go with her. At this point, she said she received a vision from God and then joined the Underground Railroad movement. She helped other escapees flee to Maryland and then to Canada when she began to distrust the American government’s ability to treat the former slaves well. There was a $40,000 bounty placed on her head, which, if you think about it, was quite the amount of money back in the 1800s.

Ennsberger? Auburn, NY, Wikimedia Commons

Ennsberger? Auburn, NY, Wikimedia Commons

Sources: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18