In 1804, President Thomas Jefferson ordered Captain Meriwether Lewis and Second Lieutenant William Clark to march west and chart the vast, unexplored interior of America. With a colorful cast of characters, Lewis and Clark spent two years hiking clear to the Pacific Ocean and back. In so doing, they united the States from sea to sea, and, it might be said, truly founded the United States as we know it today. Their expedition is enshrined in the lore of the nation, but how much do we really know about it? Here are 42 adventurous facts about the voyage of Lewis and Clark.

Lewis And Clark Expedition Facts

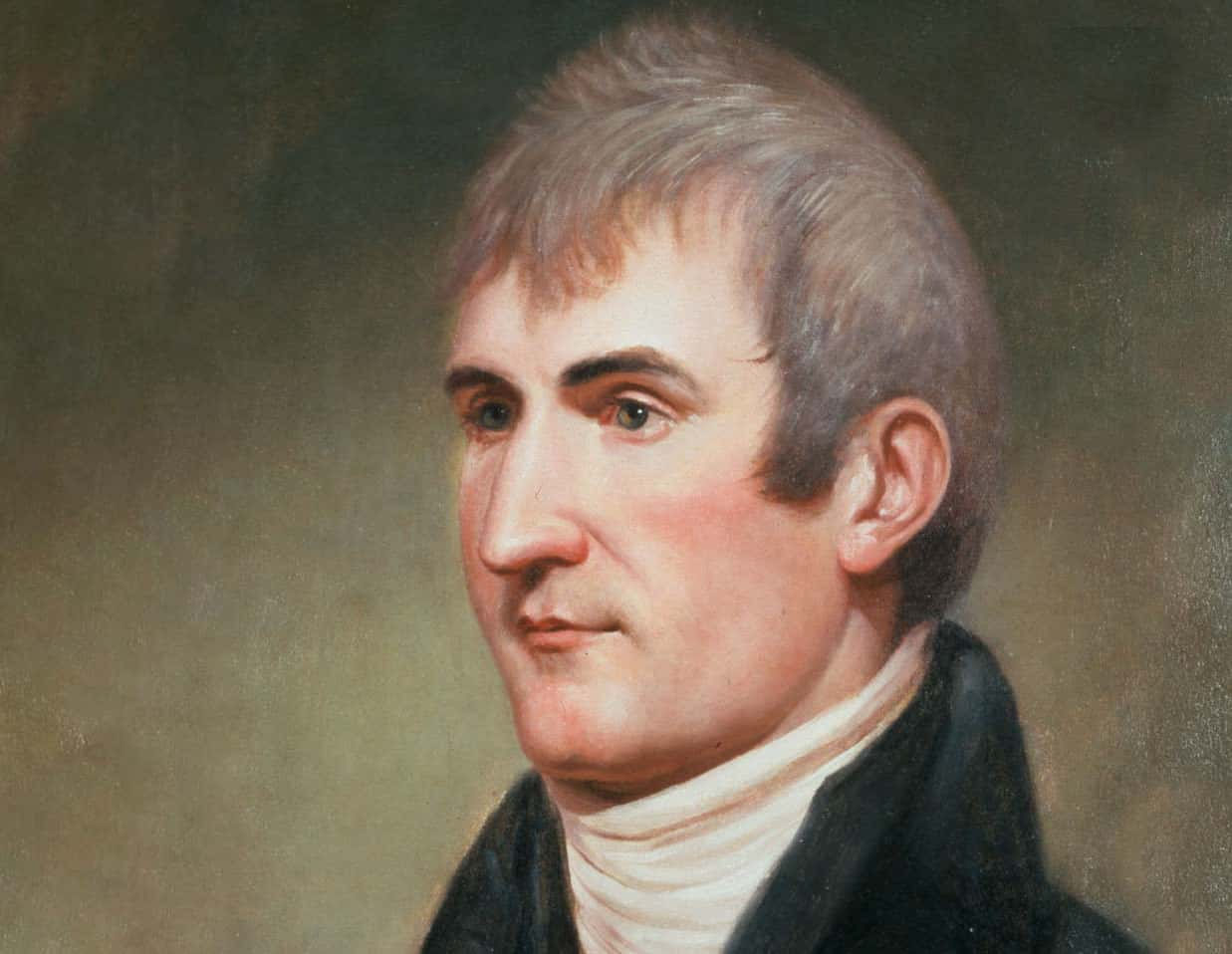

42. Humble Origins

Lewis and Clark, American history’s dynamic duo, first met in 1795. A hot-headed young soldier, Meriwether Lewis was court-martialed for drunkenly challenging his superior officer to a duel. While he wasn’t booted from the army, he was placed with a new company, under the command of one William Clark. It wouldn't be American history without a duel!

41. The Louisiana Purchase

In 1803, President Thomas Jefferson pulled off the Louisiana Purchase, the biggest one-time purchase of land in human history. For the equivalent of $300 million, the United States acquired virtually all of what is now considered the American Midwest (and just a little bit of Canada to boot) from France, as well as a sufficiently vague western border which would allow Americans to explore and claim lands clear to the Pacific Ocean.

40. The Dynamic Duo

To reach—and therefore claim for the US—the Pacific Coast, Jefferson quickly enlisted to his secretary, one Meriwether Lewis, to lead an expeditionary crew across the interior to find a passage to the sea. Lewis chose his old army buddy William Clark as co-leader.

39. Co-Captains

There was a small problem: Secretary of War Henry Dearborn, who was officially responsible for the expedition, denied Lewis the right to share command. Clark would remain, officially, Lewis’ second-in-command, but the two men referred to each other as “captain” throughout the voyage, both as a sign of respect and to hide Clark’s subordination from the rest of the Corps of Discovery.

38. The Corps of Discovery

With a budget of just $2,500 and orders to “the most direct and practicable water communication across this continent, for the purposes of commerce,” Lewis and Clark began assembling their expeditionary team. The so-called “Corps of Discovery” was made up of 33 young, unmarried men, all expert woodsmen who were given five dollars a month in exchange for their service, and a promise of 320 acres of land upon their return.

37. Louisville and Clark

Nearly a third of the Corps of Discovery came from Louisville, Kentucky. In an example of less-than-creative nicknaming, this crew became known as the Nine Young Men From Kentucky.

36. Under Pressure

In addition to the rest of their arsenal, Lewis and Clark brought along a single air rifle for protection. The Girandoni air rifle was state-of-the-art for its time, a repeating rifle capable of firing two dozen shots in seconds. The Girandoni was in general use in the Austrian army, and useful in a hunt, but Lewis and Clark mostly used it to impress or threaten the various Native American tribes they met on the journey.

35. Big Game Hunters

Believe it or not, one of Lewis and Clark's main directives was to search for animals like the woolly mammoth in the untamed reaches of Western America. Jefferson had a particularly imaginative idea of the kind of animals Lewis and Clark would find in the interior. In most cases, Jefferson made the mistake of assuming fossils which had been found in America represented still-living animals and not the prehistoric behemoths who once ruled the continent. The Corps of Discovery had special instructions to send back whatever ten-foot lions, giant sloths, and woolly mammoths they could find.

34. “That’ll Show ’em!”

Why was Jefferson so keen to find these massive prehistoric monsters thriving in the American wilderness? Well, mostly because he was insecure. A French naturalist named Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon had written a hugely popular and influential book which claimed that all the flora and fauna of the New World was inherently inferior to that of the Old World, and this argument must, therefore, be extended to human beings born and raised in America. Jefferson hoped to provide examples of gigantic beasts who, if they would not disprove Buffon’s theory, might at least eat him.

33. A Big Rock Salty Mountain

Jefferson also expected Lewis and Clark to find an entire mountain made of salt (the guy had some serious hopes out of the expedition). Salt was a hot commodity in the early 19th century and would have been a valuable export for the US. Jefferson’s expectation of a literal mountain of salt seems to be based on a poorly understood translation and probably referred to a brine-crusted rock formation near what's now Salina, Oklahoma where locals would boil water to produce salt—not quite a mountain.

32. Everything But the Kitchen Sink

Believe it or not, Lewis and Clark never did find their mammoth, but they were able to send back soil samples, seeds, various animal horns, bones and pelts, four magpies, a sharp-tailed grouse, and a prairie dog. Sadly, the four calling birds, three French hens, and two turtle doves did not survive the trip.

31. Man’s Best Friend

Lewis’ beloved Newfoundland, Seaman, accompanied them on the voyage, which he bought with $20 of the $2,500 budget. At one point, Seaman was kidnapped by a group of Native American teenagers. Lewis tracked down the kidnappers and threatened to burn down their village if his dog was not returned. He even ended up naming a creek (Seaman's Creek) after the beloved pooch.

30. York

In addition to the 33 men of the Corps of Discovery were a host of ferrymen, French Canadian fur trappers, and the occasional Native American guide. One of these “non-Corpsmen” was York, William Clark’s personal slave. While York did not want to go on the voyage in the first place (he had a wife and children), he was given no say in the matter, but soon proved himself one of the most capable and respected members of the team. York’s Islands on the Missouri River and York’s Dry Creek in Montana are named in his honor.

29. Mr. Popular

York was especially popular with the Native American tribes that the Corps of Discovery encountered, most of whom had never seen a black man before. Some even believed him to have magic powers. One probably apocryphal story from after the expedition suggests York eventually escaped slavery and joined the Crow Indians.

28. Rising in the Ranks

In 2001, in recognition of his contribution to American history, York was named an honorary sergeant of the US Army by President Bill Clinton.

27. Storms A-Brewin’

In a single day, each member of the Corps of Discovery ate a groaning nine pounds of meat. To help them digest it all, Lewis and Clark brought along bilious pills—powerful, mercury-laced laxatives—which the crew began calling "thunderclappers" or “Rush’s Thunderbolts,” after their purveyor, Dr. Benjamin Rush. No part of that sounds at all healthy.

26. Following in Their Footsteps

The concentration of mercury in Rush’s Thunderbolts was so high—60%—that researchers have been able to trace the Corps of Discovery’ footsteps by collecting mercury deposits in the soil.

25. Broken Telephone

Lewis and Clark enlisted a Shoshone woman (you might have heard of her) named Sacagawea to act as a translator. There was just one problem: she didn’t speak English. She would translate conversations into Hidatsa for her husband, Toussaint Charbonneau, who would relay then the message, in French, to Corps of Discovery member Francois Labiche, who would finally translate the message for Lewis and Clark. What do you think the odds are that every message survived that journey intact?

24. Baby on Board

Sacagawea and Charbonneau brought their infant son, Jean-Baptiste, along for the journey. The baby was beloved by everyone, including Seaman, who would sometimes carry Jean-Baptiste on his furry back.

23. Pompey’s Pillar

Lewis and Clark gave little Jean-Baptiste the nickname “Pompey,” after the Roman general. Pompey’s Pillar, a massive rock formation in Montana, is named for Jean-Baptiste, and still bears the carved signature of William Clark.

22. A Life of Adventure

After Sacagawea’s death, Clark adopted little Pompey. His life continued in an extraordinary fashion: he spent six years living with Duke Paul Wilhelm of Württemberg, the Prince of Germany, before returning to the United States to become a magistrate, gold prospector, and hunting guide.

21. Land of Liberty

Once the Corps of Discovery moved out of official US territory and into the Pacific Northwest, the group suddenly became egalitarian. Lewis and Clark extended the right to vote on such important decisions as which path to take or where to set up camp, not just to the white male team members, but to York and Sacagawea as well.

20. Suffragette Symbol

Sacagawea was adopted as symbol by the National American Woman Suffragette Association in the early 20th century. They argued Sacagawea’s participation in decision-making for the Corps of Discovery was an example of women exercising their innate right to vote.

19. Reunited

Sacagawea had had a difficult life. She was kidnapped from her family at twelve, and she didn’t marry Charbonneau so much as she had “been won by him in a card game.” The expedition offered Sacagawea one glimmer of happiness, however. When the Corps of Discovery arrived at Lemhi Pass, near present-day Idaho, to trade with the Shoshone Indians, Sacagawea was surprised to see her brother, Cameahwait, whom she had not seen in five years and who was now chief of the tribe.

18. Sickly Souvenir

The Corps of Discovery brought home all manner of mineral and fossil and pelt. Many of them also brought home something much less useful: syphilis. According to Lewis’ journals, many of the Native Americans that the Corps encountered along the way were happy to barter sex for goods. Corps members suddenly became so keen to trade that Lewis had to beg them to stop—they were running out of provisions.

17. Ripped Off

Sacagawea was never paid for her contribution to the Corps of Discovery. Since she was a woman, all of the land and money that she was entitled to went to Charbonneau.

16. No Hero’s Welcome

In another sad example of predictability, York was not paid for his service either. Upon the Discovery Corp’s return to the eastern United States, York was expected to reassume his previous role as William Clark’s slave. As you might expect, York, who had been a vital member of the team and had enjoyed full democratic privileges, was not altogether happy with this arrangement. According to some accounts, York begged Clark for his freedom until Clark got fed up and sold him to a plantation owner in Kentucky. I, for one, prefer the story of him running off to join up with a Crow tribe.

15. The Lone Casualty

At the end of the two-and-a-half-year expedition, the Corps of Discovery arrived back in Washington, D.C. Amazingly, only a single soul was lost on the voyage: Sergeant Charles Floyd died of a burst appendix three months into the trip. He's buried in Missouri, at a place now called Floyd’s Bluff.

14. Back from the Dead

At this point, no one in Washington had heard from Lewis and Clark in more than a year. The Corps of Discovery had long since ceased sending back specimens and findings. Many had assumed the Corps had all been killed by bears.

13. Life’s a Gass

The last surviving member of the Corps of Discovery, Patrick Gass, lived to be 98, and even tried to join the Union Army during the Civil War.

12. The Scenic Route

The journey of Lewis and Clark covered approximately 8,000 miles, from Missouri to the Pacific Ocean and back again.

11. Twin Cities

There are two neighboring towns named for Lewis and Clark. Lewiston, Idaho, and Clarkston, Washington sit on opposite sides of the Idaho-Washington border.

10. Flip You for It?

To commemorate the expedition, the United States Mint struck a limited edition “Lewis and Clark” gold coin. It's the only US coin to feature two “heads” sides. So remember, if anyone ever challenges you to a coin flip with a Lewis and Clark coin, do not call tails.

9. Good as Gold

Perhaps more famously, Sacagawea was also honored with a gold coin. The “Sacagawea dollar,” first struck in 2000, depicts Sacagawea and Jean-Baptiste on the “heads” side. Since 2009, the “tails” side has been changed every year, always depicting a prominent part of Native American heritage.

8. Sorry!

At one point on the return trip, the Corps split into two groups, one led by Clark, the other by Lewis, to better explore some tributaries of the Marias River. They were reunited more than a month later, where the Yellowstone and Missouri Rivers meet, when one of Clark’s men mistook Lewis for an elk and shot him in the leg.

7. Hard Liquor

Lewis and Clark also brought along 120 gallons of bourbon, the first time that a North American expedition brought a liquor other than rum. While a lot of the whiskey was traded for goods along the way, of course not all of it was reserved for such productive enterprises. The Corps of Discovery liked to mix the bourbon with molasses to make a drink they called “skull varnish.” Sounds tasty.

6. Spanish Spies

Unbeknownst to the Corps of Discovery, they were begin hunted by the Spanish Army. The Spanish, worried that Lewis and Clark might indeed gain access to the Pacific, thereby disrupting Spanish trade and settlement, set out to apprehend the entire Corps of Discovery. They had been tipped off about the expedition by US Army General James Wilkinson, who was himself a Spanish spy.

5. Close Call

Though they never succeeded in catching the expedition, the Spanish Army did once manage to get within 100 miles of the Corps—not bad considering they had the entire vast, empty, American wilderness to hide in.

4. A Wales of a Tale

Big weird animals weren’t the only thing Lewis and Clark were asked to watch for. Jefferson was also keen on finding out the truth behind a medieval legend which told of a Welsh prince who sailed across the Atlantic and settled, presumably, somewhere in the New World. Lewis and Clark did actually note some small similarities between Welsh culture and that of the Mandan tribes they encountered, which was enough to flare the imaginations of the American public for the time. However, the legend of Prince Madoc seems to be just that—a legend.

3. Dog Food

There was no shortage of edible animals and plants thriving in the American interior. Lewis and Clark had access to elk, deer, bison and turkey, as well as all sorts of berries, roots and wild vegetables. Nonetheless, the Corps of Discovery ate more than 200 dogs over the course of their trip. Most of the explorers preferred the taste of dog meat to that of venison.

2. A Bright Idea

Despite the plenitude of food the American environment provided, by the second winter the Corps of Discovery’s provisions had run low. Crossing the Rocky Mountains, with little opportunity to hunt or forage and almost out of bullets, the team resorted to eating their candles, which were made of beef tallow. Desperate measures indeed, but at least the Corps made it across the range without anyone starving to death.

1. Mysterious Death

After the expedition, William Clark returned to his military career, lived a relatively uneventful life, retired, and died. Meriwether Lewis, however, was immediately appointed governor of Upper Louisiana. Lewis’ record as governor is spotty at best—he nearly bankrupted the territory, and some claim he had become addicted to opium (but who wasn't addicted to opium at that time?). One night, while traveling to Washington to resolve some financial issues, Lewis began pacing and muttering to himself. He was found dead of gunshot wounds later that night. To this day, no one can agree if Lewis committed suicide or he was murdered.

Sources: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19