Refusing To Surrender

An unexpected result of the Japanese loss in WWII was the men of the Imperial Japanese Army and Imperial Japanese Navy who continued to fight after Japan’s surrender. These Japanese holdouts refused to surrender for a variety of reasons, but mainly they didn’t believe Japan had surrendered or they felt duty-bound to keep fighting as surrendering was considered dishonorable. This is the story of the last Japanese holdout.

The End Of WWII

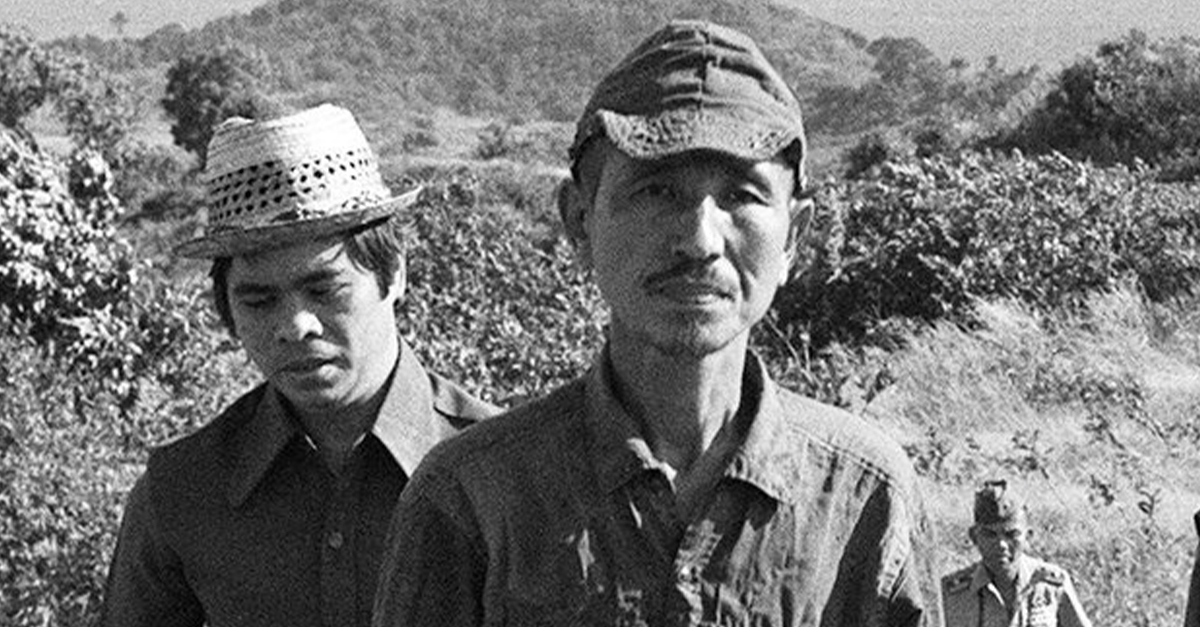

Hiroo Onoda was a second lieutenant in the Imperial Japanese Army. Believing WWII was still being fought, he carried out guerrilla warfare on the Philippines island of Lubang, on a few occasions engaging in shootouts with the locals and with Philippine authorities.

Segunda Guerra Mundial, Flickr

Segunda Guerra Mundial, Flickr

The End Of WWII

Initially, there were four Japanese holdouts on the island, having been stationed there in 1944. With the Japanese surrender, most Japanese troops were taken prisoner and sent back to Japan.

NARA, College Park, MD., Wikimedia Commons

NARA, College Park, MD., Wikimedia Commons

The End Of WWII

The relative isolation of Lubang ensured that Onoda and his three comrades were not immediately aware of Japan’s surrender in August 1945. Over the years, the other three were slain and Onoda was alone.

The Early Life Of Hiroo Onoda

Hiroo Onoda was born on March 19, 1922, in Kamekawa, Wakayama Prefecture, in the Empire of Japan. He worked for the Tajima Yoko trading company and was sent to a company branch in Wuhan, China.

The Early Life Of Hiroo Onoda

Onoda was living in China, which was under Japanese occupation, when, in 1942, he was conscripted into the Imperial Japanese Army. He trained as an intelligence officer and received further training in guerrilla tactics.

Mainichi Shimbun, Wikimedia Commons

Mainichi Shimbun, Wikimedia Commons

Deployment On Lubang Island

In December 1944, Onoda was assigned to lead guerrilla operations on Lubang Island in the Japanese-occupied Philippines. He was tasked with destroying the island’s airstrip and pier and destroying any enemy planes or boats attempting to land or dock.

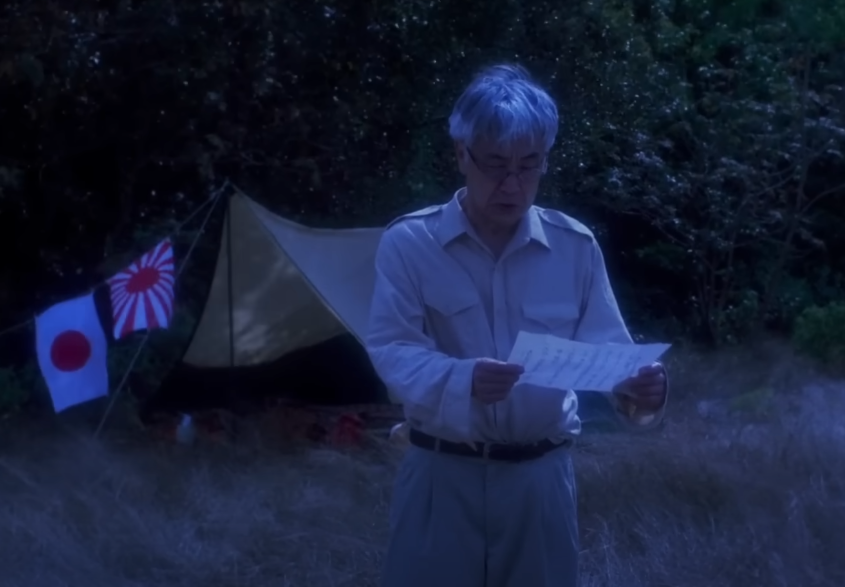

Bathysphere, Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle (2021)

Bathysphere, Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle (2021)

Deployment On Lubang Island

After arriving at Lubang, Onoda rendezvoused with the Japanese forces already on the island. Onoda had been given very specific and very clear orders that under no circumstances was he to surrender or take his own life.

Bathysphere, Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle (2021)

Bathysphere, Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle (2021)

Deployment On Lubang Island

Onoda was outranked by a number of officers on the island, and they prevented him from carrying out his orders. This left the island vulnerable to invading United States and Philippine Commonwealth forces.

Bathysphere, Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle (2021)

Bathysphere, Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle (2021)

History's most fascinating stories and darkest secrets, delivered to your inbox daily.

Japanese Surrender

When the US and Philippines did arrive, most of the Japanese left on the island surrendered to the American and the Philippine forces. This left Second Lieutenant Onoda and three others—Private Yuichi Akatsu, Corporal Shōichi Shimada, and Private First Class Kinshichi Kozuka—alone on the island.

Bathysphere, Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle (2021)

Bathysphere, Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle (2021)

Japanese Surrender

Onoda led the men into the mountains. The four men continued with their mission, carrying out guerrilla operations, while they survived on bananas, coconuts, and whatever rice and meat they could scrounge or steal from the local farmers.

Bathysphere, Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle (2021)

Bathysphere, Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle (2021)

Holding Out On Lubang Island

On a few occasions, they fought with local authorities as well as the local population, thinking they were themselves guerrillas working with the Allies. Since they were known to be there, search parties from American and Filipino authorities were frequently sent out, which Onoda and his men successfully evaded.

Bathysphere, Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle (2021)

Bathysphere, Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle (2021)

Holding Out On Lubang Island

During their time on the island, up to 30 island inhabitants were lost to Onoda and his men and their guerrilla tactics. In October 1945, leaflets were dropped on the island announcing that Japan had surrendered on August 15 and that they should “Come down from the mountains”.

Bathysphere, Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle (2021)

Bathysphere, Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle (2021)

Holding Out On Lubang Island

Thinking the leaflets were Allied propaganda, Onoda chose to ignore them. At the end of 1945, General Tomoyuki Yamashita of the Japanese Fourteenth Area Army had more leaflets dropped, explicitly ordering the men to surrender.

Unknown Japanese Army Photographer, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Japanese Army Photographer, Wikimedia Commons

Holding Out On Lubang Island

The holdouts studied the leaflets closely and determined that they were not genuine. Any attempts to find the four men would be met with weapon fire and if the search parties returned fire, Onoda and his men took that as proof there had been no surrender.

Bathysphere Productions, Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle (2021)

Bathysphere Productions, Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle (2021)

Holding Out On Lubang Island

Private Akatsu separated from the group in September 1949 and survived on his own for six months until he surrendered to Philippine forces in March 1950. The others considered this to be desertion which caused them to be even more cautious about coming into contact with anyone from the outside.

Bathysphere, Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle (2021)

Bathysphere, Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle (2021)

Holding Out On Lubang Island

Letters and photographs from the families of the three holdouts were dropped in February 1952 urging them to surrender. The group decided that this was just another Allied trick.

Bathysphere, Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle (2021)

Bathysphere, Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle (2021)

Holding Out On Lubang Island

In a shootout with local fishermen in June 1953, Corporal Shimada was wounded in the leg. The Philippine Army mountain unit accidentally encountered the holdouts while training and in the ensuing exchange of weapon fire, Shimada lost his life.

Bathysphere, Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle (2021)

Bathysphere, Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle (2021)

Holding Out On Lubang Island

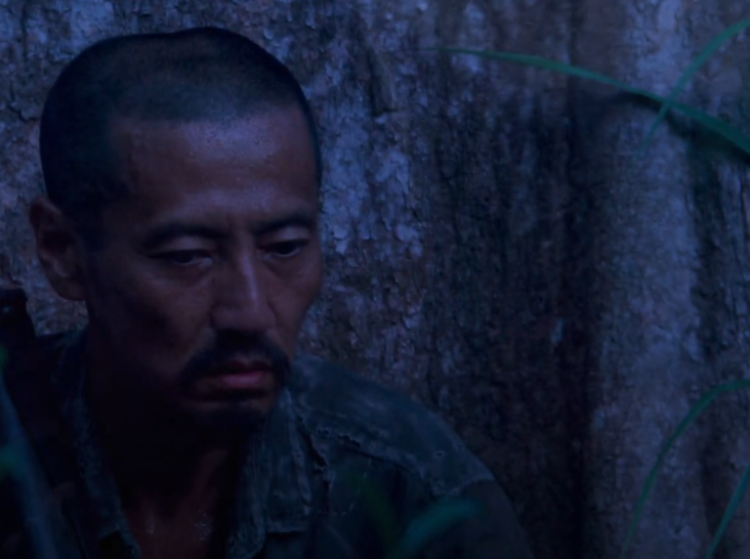

Onoda and Kozuka carried on in this way for almost 20 years when on October 19, 1972, the local authorities conducted a raid. Onoda and Kozuka had burned piles of rice stolen from local villagers in hopes of alerting Japanese forces that they were still alive and carrying out their duties.

Holding Out On Lubang Island

During the raid, Kozuka was shot and lost his life. At this point, Onoda was alone.

Norio Suzuki was a Japanese adventurer who was traveling around the world. He told his friends that he was going to find Lieutenant Onoda, a panda, and the abominable snowman, in that order.

Bathysphere, Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle (2021)

Bathysphere, Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle (2021)

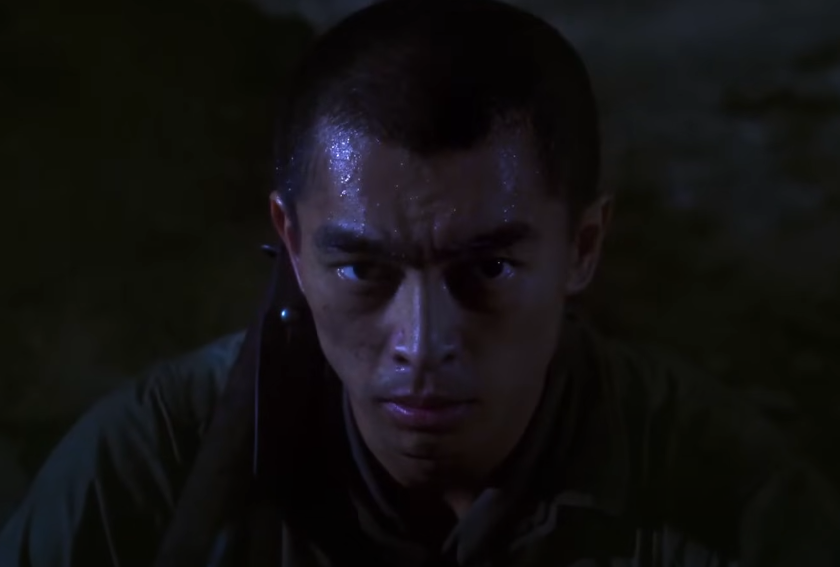

Contacting Hiroo Onoda

On February 20, 1974, after four days of searching, Suzuki encountered Onoda. In an interview later in his life, Onoda said that a “hippie boy, Suzuki, came to the island to listen to the feelings of a Japanese soldier”.

Bathysphere, Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle (2021)

Bathysphere, Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle (2021)

Contacting Hiroo Onoda

The two men became friends, but Onoda told Suzuki that he would not surrender. Onoda was going to wait for orders from his commanding officer.

Bathysphere, Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle (2021)

Bathysphere, Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle (2021)

Contacting Hiroo Onoda

Onoda’s final orders before he came to Lubang Island in 1944 came from Major Yoshimi Taniguchi, who had been commander of the Special Intelligence Squadron of the Fourteenth Area Army. However, his immediate superior was Lieutenant General Shizuo Yokoyama, commander of the Eighth Division.

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Contacting Hiroo Onoda

Suzuki took photographs of Onoda and returned to Japan to tell the world of their meeting. Yoshimi Taniguchi, now a bookseller, was tracked down by the Japanese government.

Bathysphere, Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle (2021)

Bathysphere, Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle (2021)

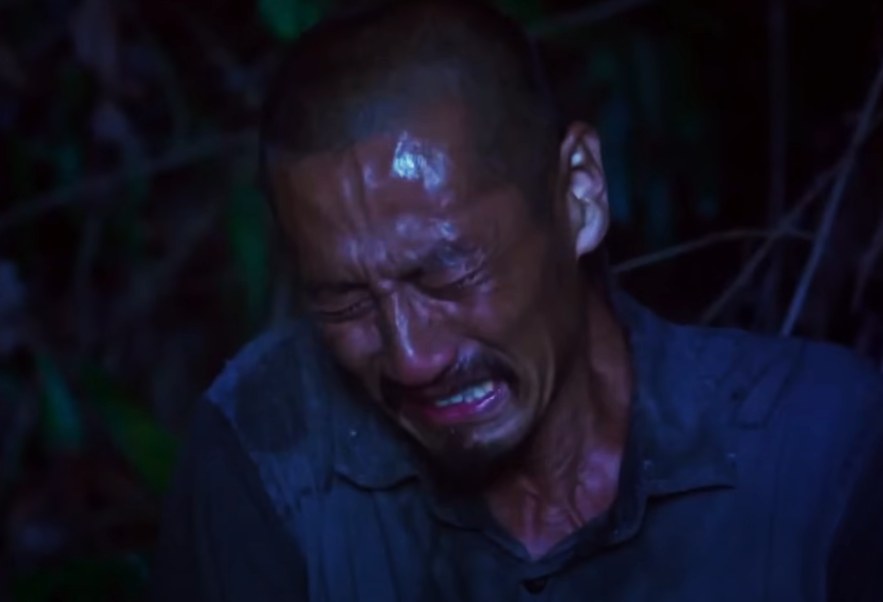

Hiroo Onoda Finally Surrenders

Taniguchi flew to Lubang with Suzuki on March 9, 1974, to meet with Onoda. Taniguchi issued the following orders to Onoda: “In accordance with the Imperial Command, the Fourteenth Area Army has ceased all combat activity”.

Bathysphere, Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle (2021)

Bathysphere, Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle (2021)

Hiroo Onoda Finally Surrenders

The orders continued with instructions that Onoda was relieved of all duties, and he was to cease all “activities and operations immediately and place themselves under the command of the nearest superior officer”.

Bathysphere, Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle (2021)

Bathysphere, Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle (2021)

Hiroo Onoda Finally Surrenders

He was further instructed to communicate with American or Philippine forces and follow their directives. Relieved of his duties, Onoda surrendered to Philippine forces at the radar base on Lubang.

Bathysphere, Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle (2021)

Bathysphere, Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle (2021)

Hiroo Onoda Finally Surrenders

On March 11, 1974, a formal surrender ceremony was held by President of the Philippines Ferdinand Marcos at Malacañang Palace in Manila. This ceremony was covered by the world media. Marcos granted Onoda a full pardon for crimes he had committed while in hiding.

Malacañang Palace, Wikimedia Commons

Malacañang Palace, Wikimedia Commons

Hiroo Onoda Finally Surrenders

Onoda turned over all his weapons, including a dagger his mother had given him in 1944 to end his life had he been captured. Onoda had held out for 28 years, six months, and eight days after Japan's surrender in 1945.

Life After Lubang Island

On returning to Japan, Onoda received a hero’s welcome. He wrote his autobiography that same year. Titled No Surrender: My Thirty-Year War, it was a best-seller.

Life After Lubang Island

Onoda had been declared dead by the Japanese government in 1959 as they believed no one could survive that long in isolation. The government offered him his back pay for all extra years of service, but he refused it.

Life After Lubang Island

Whenever well-wishers gave him money, he donated it to the Yasukuni Shrine. Onoda was unhappy with the attention he was receiving. He believed the media exposure he was receiving was part of a larger withering of traditional Japanese values.

Wiiii, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Wiiii, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Life After Lubang Island

Onoda’s elder brother Tadao lived in Brazil as a cattle farmer. Onoda soon joined him there as part of an established Japanese immigrant community in Mato Grosso do Sul. Onoda established his own cattle ranch and was married in 1976.

Bathysphere, Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle (2021)

Bathysphere, Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle (2021)

Life After Lubang Island

After 1984, Onoda spent three months of the year in Brazil and the rest of his time was spent in Japan. After reading about a Japanese teenager who had murdered his own parents, Onoda established the Onoda Shizen Juku (“Onoda Nature School”) educational camp for young people, held at various locations in Japan.

Bathysphere, Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle (2021)

Bathysphere, Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle (2021)

Life After Lubang Island

The Filipino media, in a series of interviews with villagers from Lubang, reported that the villagers alleged Onoda and his men were responsible for taking the lives of up to 30 civilians. Onoda didn’t mention those losses of life in his autobiography.

Bathysphere, Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle (2021)

Bathysphere, Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle (2021)

Life After Lubang Island

In 1996, Onoda visited Lubang for the first time since he left. He and his wife Machie established a $10,000 (USD) scholarship for the local school. The island’s town council asked him to compensate the families of those lives he had allegedly taken, while villagers protested his visit.

Bathysphere, Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle (2021)

Bathysphere, Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle (2021)

Life After Lubang Island

Onoda was awarded the Santos-Dumont Merit Medal by the Brazilian Air Force on December 6, 2004. In 2006, his wife Machie became the head of the conservative Japan Women's Association, which was established in 2001 by the ultranationalist organization Nippon Kaigi.

Palácio do Planalto, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Palácio do Planalto, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Life After Lubang Island

On February 21, 2019, the Legislative Assembly of Mato Grosso do Sul awarded him the title of Cidadão ("Citizen"). On January 16, 2014, Onoda succumbed to heart failure resulting from pneumonia at St Luke's International Hospital in Tokyo.

Bathysphere, Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle (2021)

Bathysphere, Onoda: 10,000 Nights in the Jungle (2021)

Life After Lubang Island

Onoda’s strange and exceptional life was celebrated as much as some of his choices were questioned. Japanese Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshihide Suga commented on Onoda’s passing: "I vividly remember that I was reassured of the end of the war when Mr Onoda returned to Japan".