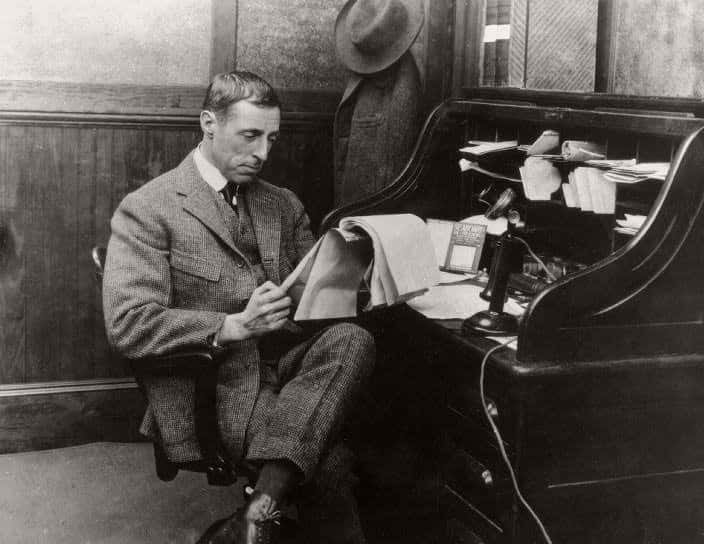

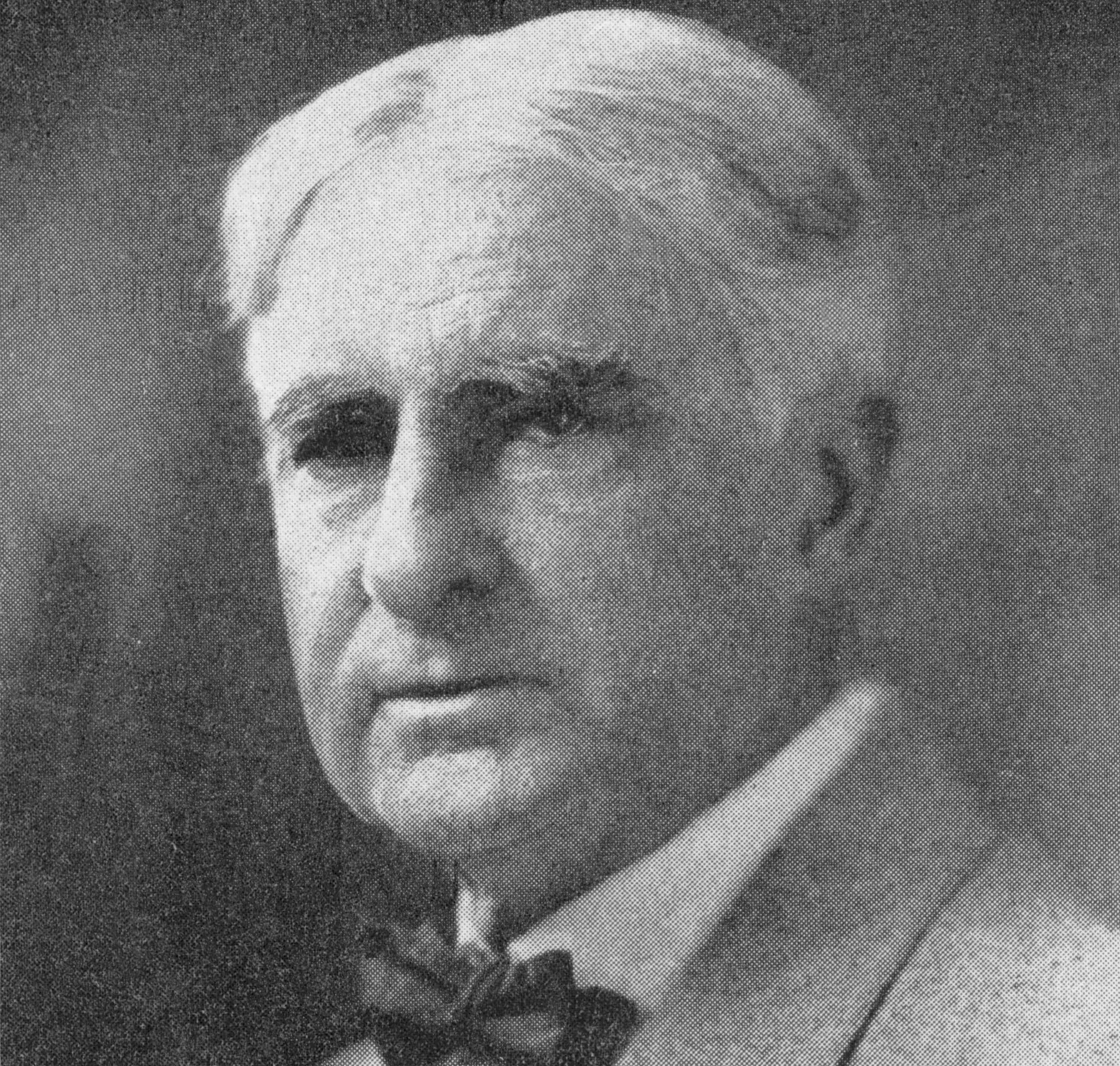

There is hardly a film director in Hollywood history more important—or controversial—than D.W. Griffith. During the early years of Hollywood, Griffith’s filmmaking skills were nothing short of groundbreaking. His techniques influenced filmmaking to this day, and his style was copied to the point that they became normal for Hollywood films, and other films worldwide. However, such a shining legacy will forever be tainted by the subject matter which Griffith chose for his most famous film. Continue reading to find out more about D.W. Griffith.

1. Birth of a Filmmaker

David Wark Griffith was born on a farm on January 22, 1875, in Oldham County, Kentucky.

2. Too Poor for School

For a man whose life and legacy would inspire so many mentions in college film history courses, D.W. Griffith’s personal education was very sparse. His primary school consisted of a one-room building, and the person who was most often his teacher was his older sister, Mattie. His secondary school education was later cut short due to his family’s poverty. Griffith was needed to help support the family financially.

3. Does That Count as Promotion?

As a youth, D.W. Griffith supported his family by working in a dry goods store. He later switched to working in a bookstore.

4. Starting Short

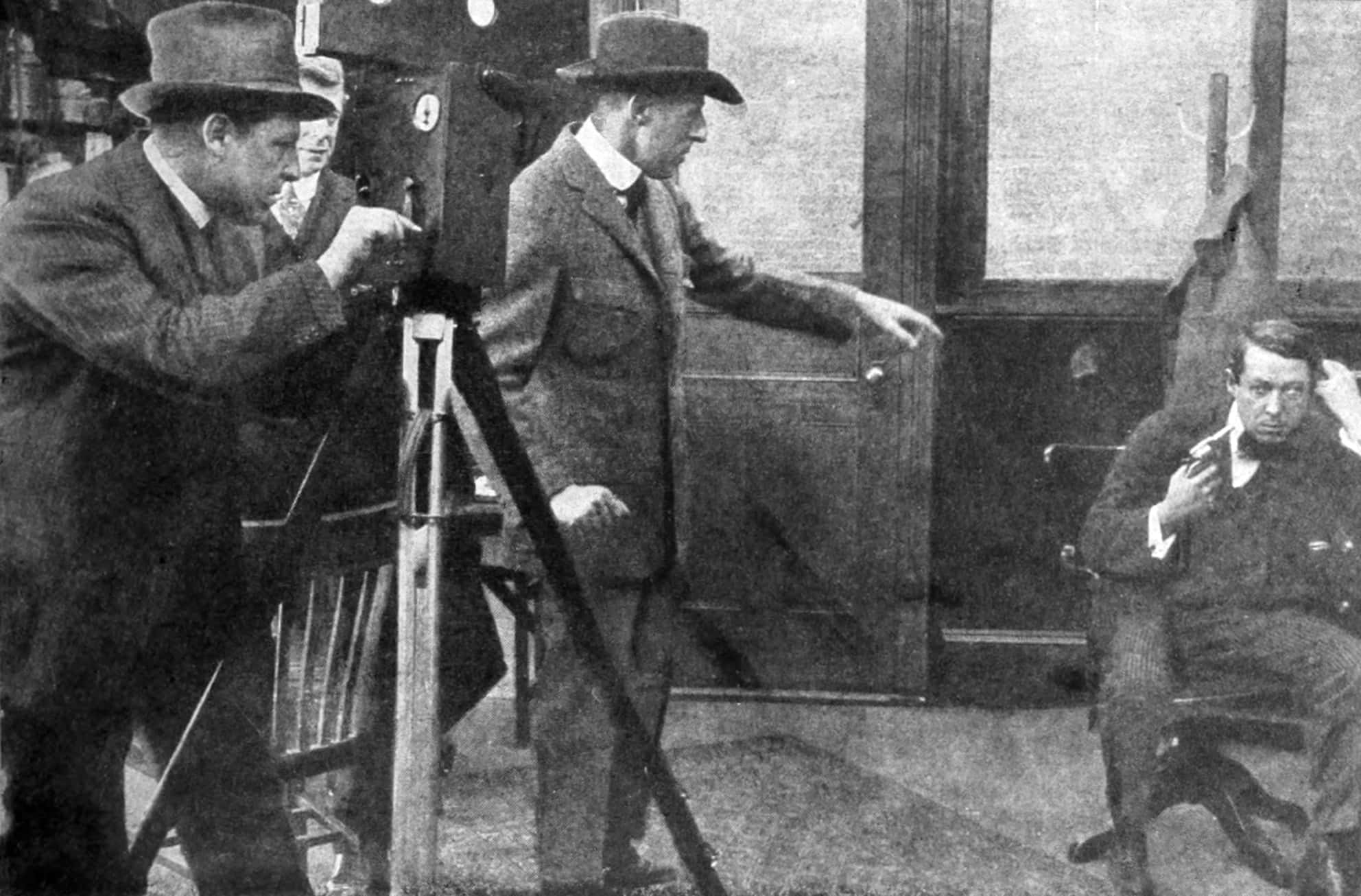

The first film that Griffith ever directed was a 12-minute silent film titled The Adventures of Dollie. Released in 1908, it was produced by Biograph Company, which Griffith worked with for much of his film career.

5. I Should have Trademarked it!

It’s safe to say that if there’s one phrase associated with a film director to this day, it would be the three-word phrase “Lights, Camera, Action!” Given whose name is at the top of this article, you’ve probably figured out by now that the phrase originated with Griffith. He first said it in 1910 while he was filming In Old California. The rest is history.

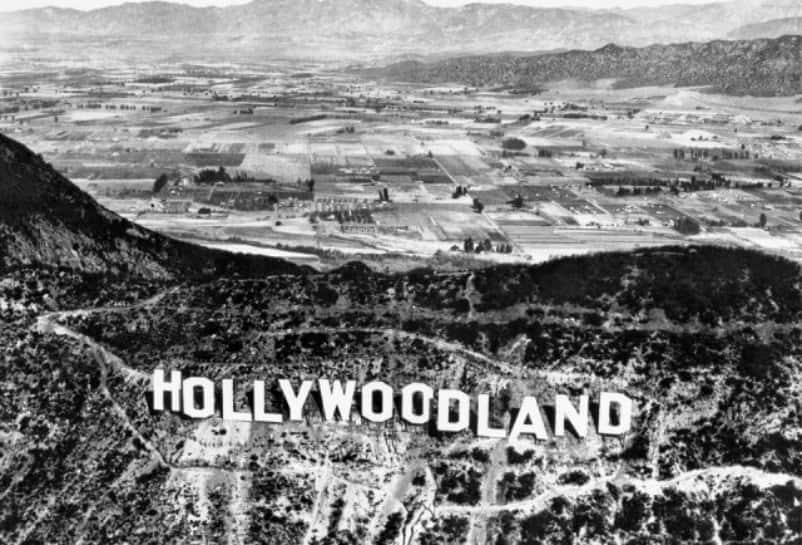

6. Setting a Lucrative Precedent

Speaking of Griffith’s In Old California, this short film actually holds the distinction of being the very first film that shot in Hollywood, California. It certainly wasn’t the last either!

7. Infamous Father

Griffith’s father was Jacob Wark Griffith. Nicknamed “Roaring Jake,” Jacob fought for the Confederacy during the American Civil War and held the rank of colonel. After the war ended, Jacob became a state legislator in Kentucky. He died when Griffith was just 10 years old.

8. Nice Consolation?

Before D.W. Griffith ever got close to a film camera, he worked as an actor with a touring company. It wasn’t his original intention, we should note. The young Griffith initially approached the Edison Company in an attempt to sell a story he’d written. They turned him down but hired him on as an actor instead. Maybe he just gave a really convincing pitch?

9. Where’s D.W.?

If you’re interested in finding Griffith’s star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, go to 6535 Hollywood Boulevard.

History's most fascinating stories and darkest secrets, delivered to your inbox daily.

10. A Reason to Visit Kentucky?

In 1913, Griffith purchased a house in La Grange, Kentucky, for his mother to live in. Various members of Griffith’s family lived in the house, including Griffith himself and his second wife, until 1950, when Griffith’s niece sold it. The house has since become preserved as a historic building and is known as the D.W. Griffith House.

There is even a signature by Griffith left in the concrete of the sidewalk near the house.

11. Recycle and Reuse

Griffith was known for having a few tricks up his sleeve to save costs on his films. For example, if someone made an error during a take, Griffith wouldn’t yell “cut” like any other director would. Rather, he would take another scene which took place during the same set-up and have his actors perform that instead, so the take wouldn’t be wasted.

12. Not a People Person

According to those who knew him, D.W. Griffith didn’t have a single funny bone in his body. Moreover, he was reputed to have had a highly authoritative disposition.

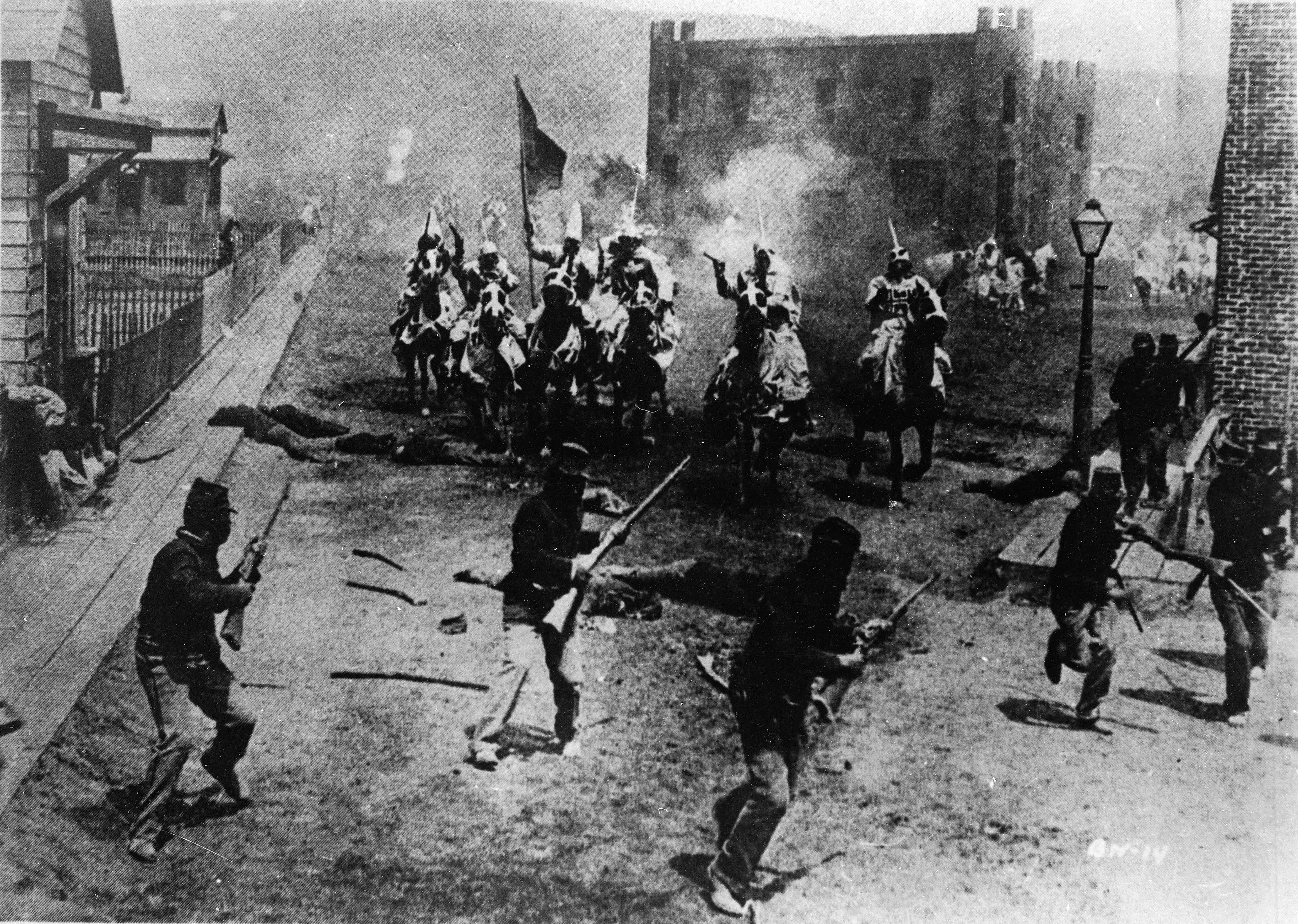

13. Acknowledging Innovation (and Nothing Else!)

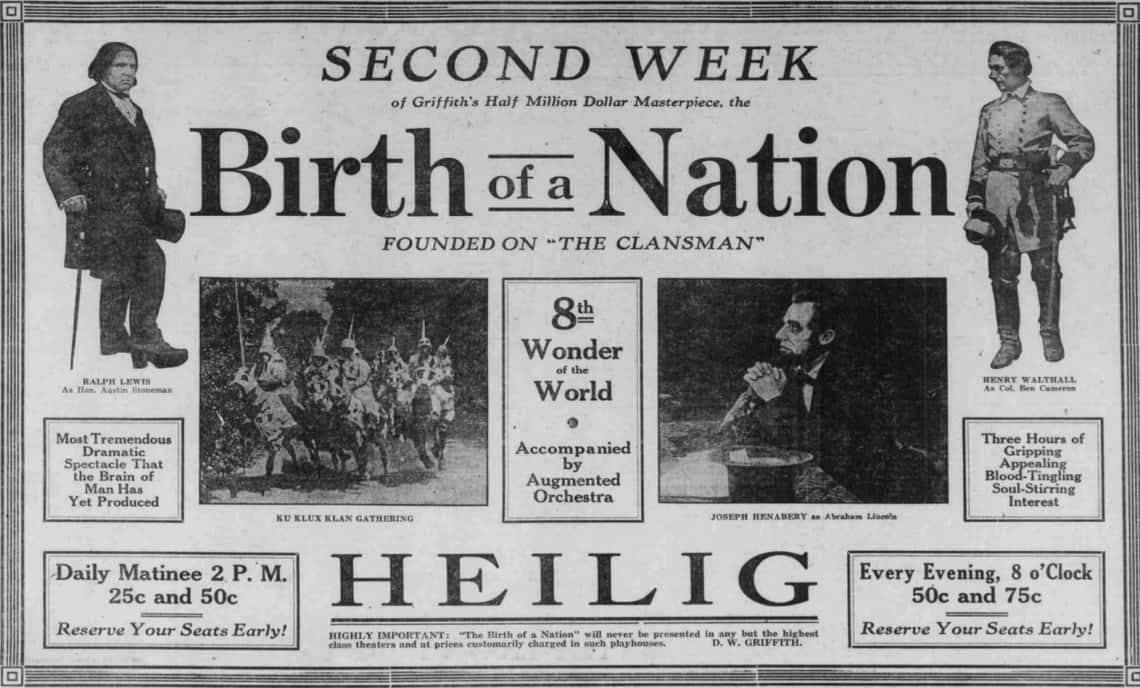

Although The Birth of a Nation has become reviled for its use of blackface and its glorification of the Ku Klux Klan, Griffith’s film nevertheless was responsible pioneering film techniques which are still used to this day. These techniques include night photography, still shots, panning shots, panoramic long shots, color tinting to indicate drama, and carefully staging a scene to make hundreds of extras look like thousands.

This has caused some scholars to declare that Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation marked the beginning of modern American cinema.

14. As Played By…

Moments from Griffith’s film career were re-enacted for a 1951 episode of Philco Television Playhouse titled “The Birth of the Movies.” Griffith himself was portrayed onscreen by John Newland. Sadly, this episode aired after Griffith died, so we won’t know what he would have thought of Newland’s performance.

15. Classic Company

In 1920, Griffith helped establish the film production company known as United Artists, along with stars Mary Pickford, Charlie Chaplin, and Douglas Fairbanks. The idea was to allow actors to have more control over their own projects as opposed to the iron grip that most Hollywood film companies had over their employees.

As of 2019, the studio is still going, albeit renamed “United Artists Digital Studios.” Among the many films released by United Artists include Rocky, several films in the James Bond series, and High Noon.

16. Sayonara, UA!

Despite the long lifespan of United Artists, D.W. Griffith was only involved with it for a very short percentage of that time. Founding it in 1919, Griffith jumped ship just five years later amid the company’s floundering profitability and diminishing returns. It didn’t help that Griffith’s 1924 film Isn’t Life Wonderful was a box office failure.

17. Love and Marriage

Griffith was married to two different women throughout his career, both of them actresses. He married Linda Arvidson in 1906 and Evelyn Baldwin in 1936. Both the marriages ended in divorce and no children.

18. Boy, was I Busy!

With more than 450 short films and 80 feature films under his belt, D.W. Griffith is one of the most prolific film directors in the history of Hollywood. In fact, if we leave out television directors, he ranks fourth in film history! The only people who made more films than him was Louis Feuillade, Georges Melies, and Dave Fleischer.

19. That’s a Lot of Films!

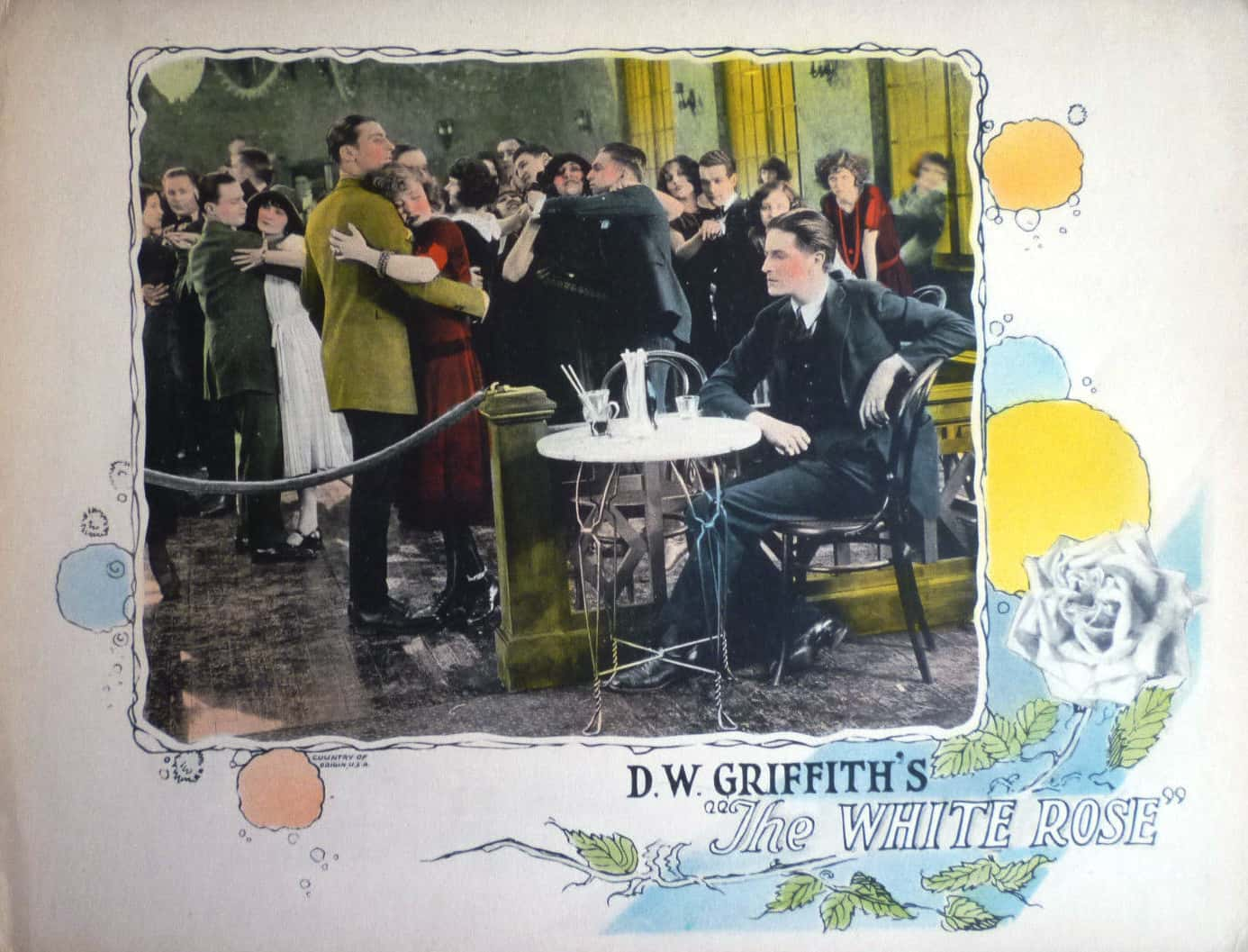

One actress who worked extensively with Griffith was Mae Marsh. In 13 years, beginning in 1910 and ending in 1923, the two of them worked on more than 50 films together. Their first collaboration was Ramona, and their final one was The White Rose.

20. Positive Working Relationship

Another one of Griffith’s most frequent collaborators was actress Lillian Gish. Working on 46 different films together, they both got their start working with The Biograph Company. Griffith was the first filmmaker to give Gish any work when she began her career. Even outside of their frequent collaborations, it was clear that Gish and Griffith had the utmost respect for each other.

Gish referred to Griffith as “the father of film,” while Griffith once remarked that his time working with Gish had represented the high watermark of his own film career.

21. Couldn’t Make it an Even 50?

In 1908 alone, Griffith made 48 short films while working for The Biograph Company! We can assume that he didn’t take any sick days that year.

22. Makes Sense?

Despite being an American, D.W. Griffith has been portrayed by British actor Charles Dance in Good Morning Babylon and Canadian actor Colm Feore in And Starring Pancho Villa as Himself.

Colm Feore

23. Boycotting Racism

Despite the fact that Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation was a massive box office hit, not everybody responded positively to the film, even at the time. The film was banned from theatres in several American cities, and protests met the film where it was screened. Not surprisingly, one of the groups in strongest opposition to the film was the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

24. Back-Handed Compliment

If you want to find a silver lining Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation, consider the fact that the film inspired many black artists to change their portrayals in pop culture by making their own films to tell their own stories. If there was ever something positive that someone could say about such a film as The Birth of a Nation, that would arguably be it.

25. You’ll Go Far

During D.W. Griffith’s time with The Biograph Company, many other famed actors and directors got their first gigs in the film industry working with Griffith. These include Lionel Barrymore (It’s a Wonderful Life), Mary Pickford (Coquette), Erich von Stroheim (Sunset Boulevard), and Dorothy Gish (Nell Gwyn).

26. Who’s Going to Model for the Statue?

In 1929, Griffith got together with several other figures in the film industry (including Darryl F. Zanuck, Ernst Lubitsch, and William C. DeMille). This group of Hollywood elites were responsible for the foundation of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. You might know this organization as the one behind the Academy Awards, those prestigious film awards which still last to this day.

27. Intentions Vs. Results

Given how Griffith’s reputation has suffered from the label of racism, it might be considered ironic that he himself dedicated many of his early films criticizing how the United States government traditionally treated Native Americans over the years. The most notable films that he made to depict the oppression of Native Americans were arguably Ramona and The Red Man’s View, which is a title that hasn’t quite aged well, regardless of Griffith’s original intent.

28. What Might Have Been

In 1926, Griffith began work on an autobiography. However, he was never able to finish it before he died. Whatever tell-all secrets he wanted to reveal in this unfinished book, he took to the grave with him.

29. Building Suspense

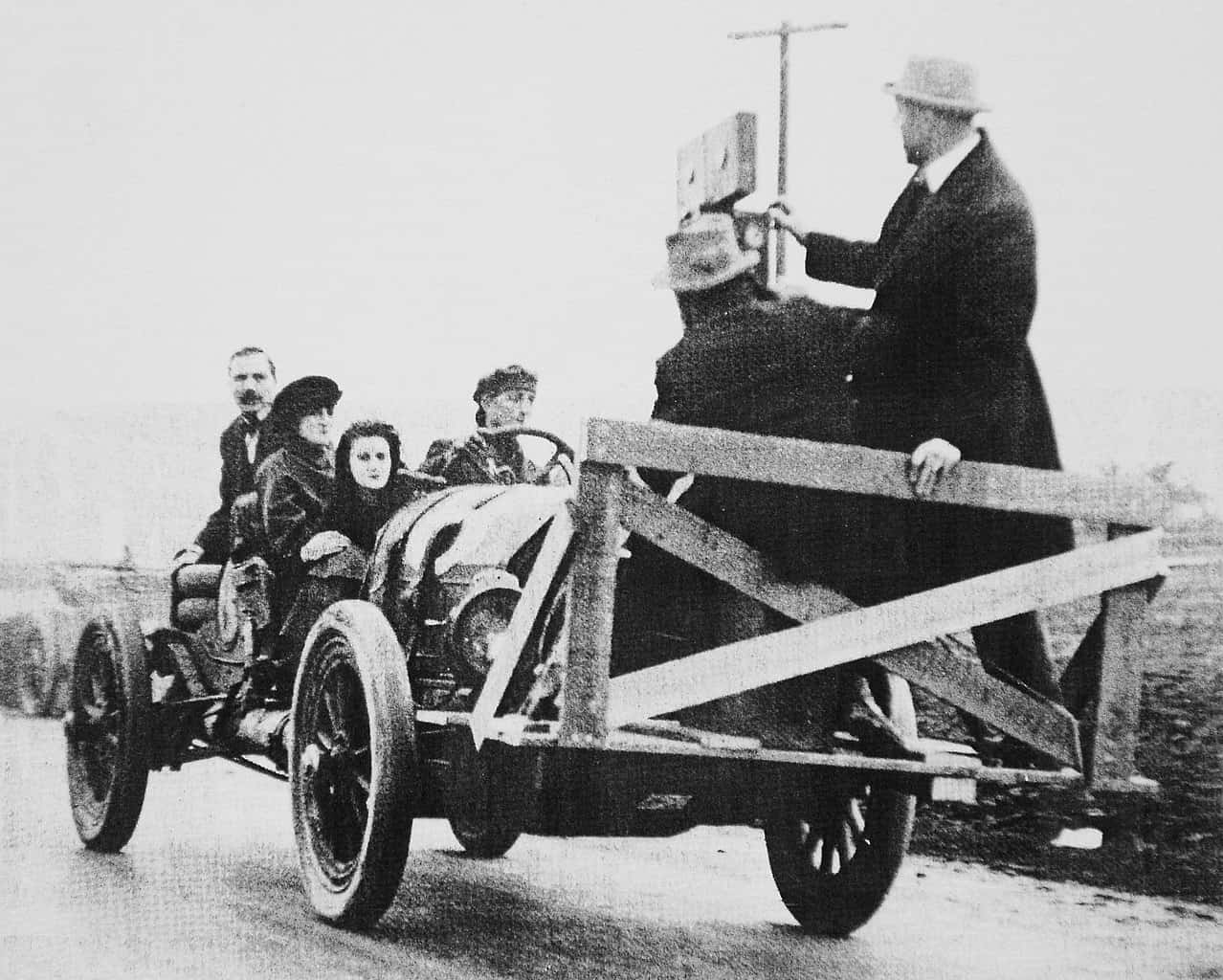

D.W. Griffith was known for pioneering the technique known as parallel editing. Also known as cross-cutting, the technique depicts two or more scenes in different locations playing out simultaneously. This allowed for more drama or suspense to be imparted in a film. One of the first films to utilize parallel editing was Griffith’s A Corner in Wheat.

30. Couldn’t Clean Up After Yourself, Could You?

One of the main sets of Griffith’s Intolerance: Love’s Struggle Throughout the Ages was meant to represent the ancient city of Babylon. After the filming was completed, Griffith was told by the Los Angeles Fire Department that the Babylonian set was a fire hazard and it needed to be demolished. However, Griffith had run out of money and couldn’t afford such an action.

As a result, the set stood for four more years before it was finally taken down in 1919.

31. Wait, That’s Why?!

You might be wondering why Griffith, after making a film which was so positive towards the Ku Klux Klan, was so determined to make the gargantuan epic Intolerance: Love’s Struggle Throughout the Ages. It turns out that Griffith was baffled and frustrated by the protests that The Birth of a Nation received from a significant portion of audiences.

Griffith took these protests as personal attacks and was determined to make a film which warned his audiences about the dangers of intolerance. We’ll just step back and let you all shake your head at that kind of twisted logic.

32. Saving These for Later

Six films that Griffith directed are currently being preserved as part of the National Film Registry. Chosen by the Library of Congress for being “culturally, historically, or aesthetically” significant, these films are A Corner in Wheat, The Musketeers of Pig Alley, Lady Helen’s Escapade, The Birth of a Nation, Broken Blossoms, and Intolerance: Love’s Struggle Throughout the Ages.

33. Whoops!

At the time that Griffith began working on the film Intolerance: Love’s Struggle Throughout the Ages, it held the record for the most expensive film ever made. Much of the film’s budget came from Griffith himself, so determined was he to make a truly epic motion picture. Unfortunately for Griffith, Intolerance was a box office flop and caused Griffith financial problems for the rest of his life.

34. Curse You, Russia!

Despite the financial failure of Intolerance: Love’s Struggle Throughout the Ages, it was actually a wild success in the Soviet Union when it was taken abroad. However, the copies of the film were often pirated and screened without D.W. Griffith’s permission. As a result, Griffith didn’t make a penny out of all those Russian screenings.

35. Time to Eat Crow!

Speaking of Griffith’s work with United Artists, one of their first films came about in a rather furious bout over artistic opinion. In 1919, Griffith directed the film Broken Blossoms for the Artcraft Company, which was headed by Adolph Zukor at the time. However, when Griffith delivered the finished film, Zukor was outraged at what he thought was an inferior-quality film.

Zukor proceeded to verbally admonish Griffith to his face. Griffith was so angry that he returned the next day with $250,000 in cash, declaring that he’d buy the film and distribute it himself. Zukor agreed, but he would live to regret it. Broken Blossoms, released through United Artists, was a critical and commercial triumph.

36. Landmark Film

In 1912, Griffith directed the film The Musketeers of Pig Alley. This film is significant for a number of reasons. For one thing, The Musketeers of Pig Alley is widely recognized as making the first modern American gangster film. It is also considered to be the first time that the filming technique known as follow-focus was used (this is when the background fades out in favor of the characters in the foreground as they move along).

37. Defining Irony

Four years before he directed the 1915 film The Birth of a Nation, Griffith directed the film The Rose of Kentucky. Unlike The Birth of a Nation, Griffith’s 1911 film was a sharp criticism of the Ku Klux Klan, depicting them in a villainous light. Of course, it certainly isn’t as well remembered as his film glorifying the KKK.

38. I’m Getting Bored of Wide Shots!

While it would be highly inaccurate to say that Griffith was the first person in Hollywood to use a close-up shot in his films, he was the man who popularized that film technique. Griffith emphasized the power of a close-up shot by having his actors heavily made up for these shots. While the initial purpose was to accentuate his actors’ features and emotions, Griffith’s tactic is seen as very hammy nowadays.

That said, his popularization of this film technique cannot be ignored.

39. Presidential Endorsement

One of the most infamous stories connected to the release of Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation occurred when it was screened at the White House—the first film to have that honor. Upon seeing it, US President Woodrow Wilson was reported to have said “It is like writing history with lightning. And my only regret is that it is all so terribly true."

Of course, following the negative backlash to the film, Wilson claimed that he was ignorant to what the film was going to be about when he approved its screening.

40. Strictly Business

Before he was able to make the film The Birth of a Nation, Griffith needed to acquire the rights to Thomas Dixon Jr.’s The Clansman, the play upon which the film was based. Dixon was adamant in his asking price of $10,000, however, and Griffith couldn’t even come up with half that. As a result, he instead offered Dixon a 25% interest in the film.

Dixon needed a lot of persuading to agree to that proposition, but we can assume that he heartily thanked Griffith when the film became the highest grossing American film ever made until Gone with the Wind, nearly a quarter of a century later.

41. That’s Far Too Long!

Griffith’s time with The Biograph Company came to an end after Griffith completed filming Judith of Bethulia. At 61 minutes, it was the first full-length film produced by Biograph, but the company was concerned about a 61-minute film being too long for audiences to endure. Griffith parted ways with Biograph over this disagreement.

In an act of spite, Biograph purposefully didn’t release Judith of Bethulia until 1914 so that Griffith was stiffed out of the profit-sharing agreement.

42. The Death of the Director

By 1948, Griffith was living alone at the Knickerbocker Hotel in Los Angeles. On July 23, he was found unconscious and rushed to the hospital. However, he died of a cerebral hemorrhage on the way there. He was 73 years old at the time.

Sources: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20