They called her one of the most beautiful women of the silent screen era, but Corinne Griffith's stint as an actor was only the beginning of a life full of glamor, husbands, and wealth. As it turned out, it was also a life full of lies: some for profit, some for fun, and some were just plain weird. Let’s sift through the stories about Corinne Griffith and figure out what’s fact and what’s fiction.

1. Even Her Birth Was A Lie

At her birth, in Texarkana, Texas in 1894, Corinne Griffith was actually Corinne Griffin. Her father was two things: a church minister and a train conductor. Other reports have him as the mayor of Texarkana. He was also a full two decades older than Griffith’s mother, who was just 20 years old. Even though Griffith was born in Texarkana, she later insisted her birthplace was in nearby Waco.

A harmless lie? Well, Griffith was just getting started.

2. She Got A Phone Call

Griffith had a younger sister, and mom and dad soon shipped the two girls off to boarding school. It wasn’t, however, one of those fancy schools you hear about in Switzerland. Griffith and her sister Augusta attended Sacred Heart Convent in New Orleans. Life went on without disturbance until 1912, when a tragic phone call came to the girls at school. Their father had suddenly died.

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

3. She Was A Winner

Griffith soon got over losing her dad and entered and won a Mardi Gras beauty pageant in New Orleans. Little did Griffith know, there was someone in the audience that had the ability to make a great change in Griffith’s life. The man was Rollin S Sturgeon, and he approached Griffith right after the pageant ended. Sturgeon stunned Griffith by telling her that she had a future in show business.

Griffith was more than a little interested and followed Sturgeon back to Hollywood. It sounds like every young woman’s dream. Well, it may be just that: or maybe even a total lie.

4. Or Maybe It Was Santa Monica

There are other accounts about how Griffith found her way to Hollywood pictures. One story goes that after her father’s passing, Griffith, her mother and sister moved to Southern California. In this tale, the beauty pageant was in Santa Monica, and Sturgeon wasn’t just in the audience, he was the pageant’s judge. Again, Sturgeon offered her a contract after Griffith won the contest. This also, however, may not be the truth.

5. Story Number Three

In this final story there was no beauty pageant at all. Once again, Griffith had moved to Southern California with her mother and sister and she just met Sturgeon at a high society party in Crescent City. Sturgeon offered her a contract with Vitagraph right then and there. So why are there three different stories about how Griffith found her way to Hollywood? It’s because, as we’ll soon see, few things are as they seem when it comes to Corinne Griffith.

6. She Signed On

What film historians do agree on is that it was in 1916 that Griffith signed a contract with Vitagraph films. The studio paid her $15 per week, and here was when she changed her name from Griffin to Griffith—no one seems to know why. Her first roles for Vitagraph were in short films, and she appeared opposite silent film star Earle Williams. For Griffith, there was still the burning question: would these small roles lead to anything?

7. She Got Two

In 1920, Griffith got her big break. She didn’t just get a role in Vitagraph’s next feature film, she got two roles. Her part in The Broadway Bubble was playing a character named Adrienne Landreth and her twin sister as well. It was the role of a lifetime, and Griffith didn’t hold back at all. Later critics called it the crowning achievement of her career. As we’ll soon see, playing her own sister would be a warm up for Griffith's wacky and mysterious life off-screen as well.

8. She Tied A Knot

Around the same time as The Broadway Bubble came out, Griffith had a romance going on. She met and married Webster Campbell who was also in show business. Campbell was a screenwriter, actor and producer, so the match had the potential to be heavenly for Griffith’s career as well as her personal life. Instead of being heavenly, it was something quite the opposite.

9. She Cut Ties

Three years into her marriage, Griffith made a disturbing realization. Her marriage had been a huge mistake and her career was going nowhere. Her husband had a problem with booze and, even more tragically, he was abusive. Griffith didn’t waste any time and gave him the heave-ho. While she was at it, Griffith looked at her lousy contract with Vitagraph and decided to cut that one up as well.

She knew she was worth more than what they were paying, and she set out to find a studio that would pay her a wage that matched her star power.

History's most fascinating stories and darkest secrets, delivered to your inbox daily.

10. She Found A Better Deal

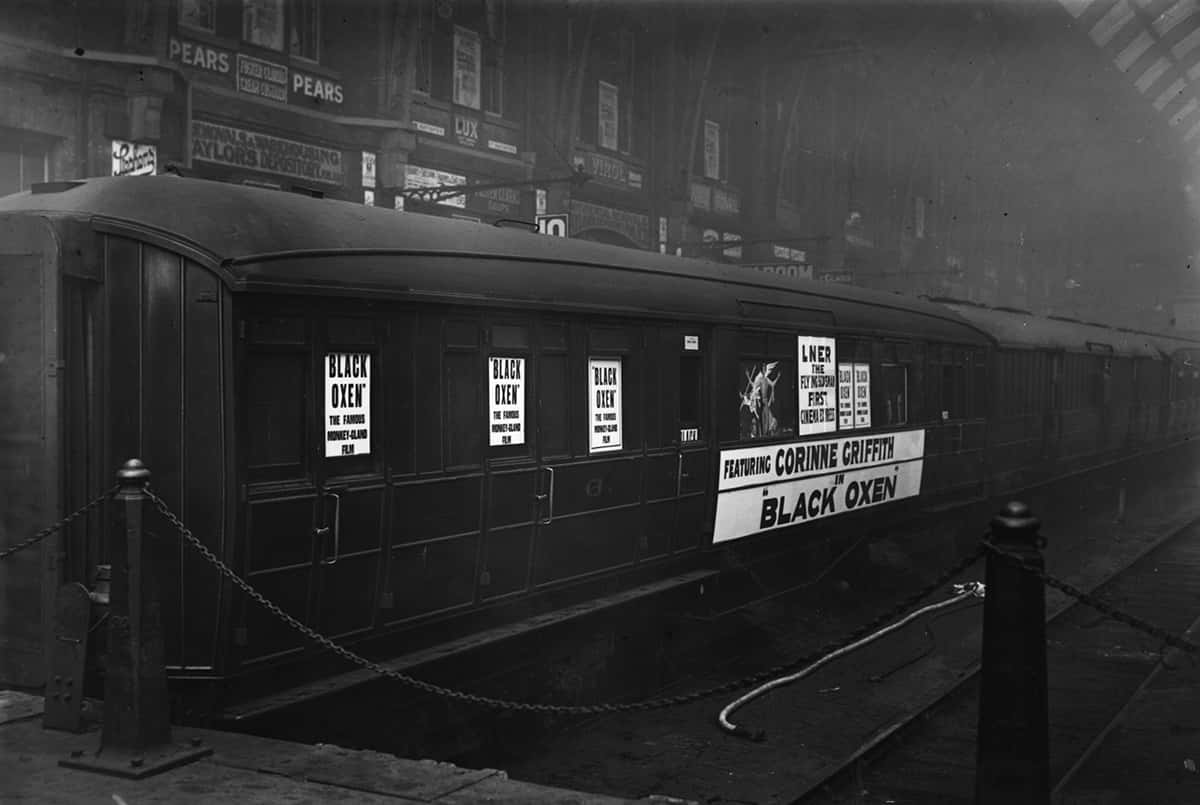

Griffith said good-bye to her husband and Vitagraph, and hello to a much better situation at First National Pictures. This was quite a huge step up as this studio agreed to pay her $2,500 a week. Now, however, she had to prove to the studio that she was worth such an enormous fee. Her first film with First National Pictures was Black Oxen and the stakes to prove herself could not have been higher.

11. She Discovered The Fountain Of Youth

In Black Oxen, Griffith again played a dual role—well, sort of. She plays an aging European socialite who discovers a miraculous fountain of youth. Well, it's actually a series of glandular treatments and surgery using X-rays that make her look years younger. Griffith's character uses her new found youth to rope in a younger lover—with the expected confusion following. The film was a hit, which solidified Griffith’s popularity in Hollywood.

Griffith’s tangled personal life would eventually resemble the plot of this movie—but it was even more twisted.

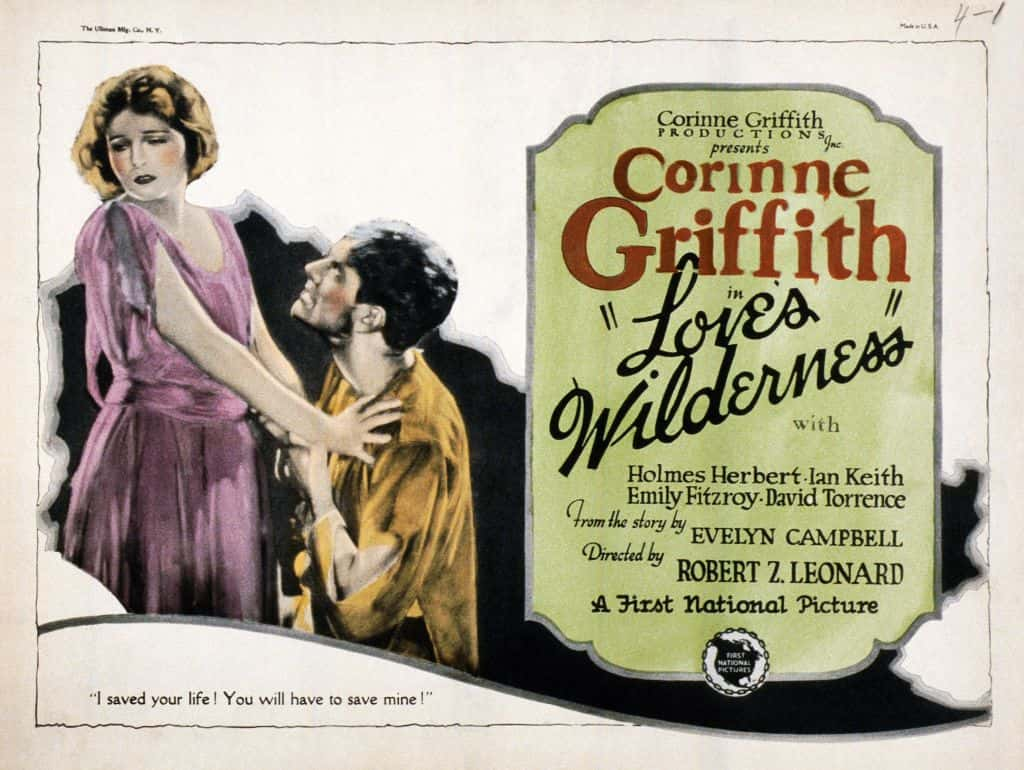

12. She Took Notes

Griffith followed Black Oxen with a string of hit films including 1924 Love’s Wilderness. In this film Griffith’s on screen husband does something strange: he pretends to have died in order to be free to live the life he wants. As we’ll soon see, it seems that Griffith was taking notes from her films to prepare for some of the more bizarre aspects of her later life.

13. She Had A Deja Vu

While making hit films and solidifying her career in Hollywood, Griffith also had time for romance. She followed her divorce with a new husband who sounds a lot like the old one. In 1924, she married Walter Morosco: a producer, writer, director and actor. We can only hope he didn’t have the same destructive traits that Webster Campbell had.

Wikimedia Commons Corinne Griffith and Walter Morosco

Wikimedia Commons Corinne Griffith and Walter Morosco

14. She Played It Smart

Griffith was fiercely independent and wanted to make sure she could take care of herself. When the money started rolling in from her films, she did something smart: invested it. Griffith chose real estate as her way to increase her fortune—and it was a very smart move. By 1927, she’d amassed a whopping $500,000 in various properties. I believe the expression is: you go girl!

Real estate was, however, just the tip of the iceberg for enterprising Griffth.

15. She Did Their Job Too

Griffith made three back to back hits for First National Pictures and, in 1928, decided she’d had enough with studios—so she took a giant risk. She formed Corinne Griffith Productions with her husband Morosco. Griffith was ready to show the studios that she could do both her job and theirs. Her first film was The Garden of Eden, which United Artists would release.

I think it’s safe to assume Griffith was beside herself with worry. She’d burnt her bridges with the studios—but would the film be a hit?

Wikimedia Commons Corinne Griffith and Walter Morosco

Wikimedia Commons Corinne Griffith and Walter Morosco

16. They Stayed Away

While critics gave The Garden of Eden an enthusiastic thumbs up, audiences didn’t quite agree and generally stayed away. Griffith hated appearing in a box office flop—and this was worse because she was now also the producer. She floundered for a bit, looking for the next direction for her career. This was when she made a surprising choice: she went back with First National Pictures.

It seemed like a huge step backwards for Griffith—it was, however, anything but.

17. She Got The Nod

In 1929, Griffith appeared in The Divine Lady—based on a true story of a love affair between Admiral Nelson and Emma Hamilton. The film, produced by her husband, was a huge hit, as was Griffith’s performance. The newly formed Academy Awards nominated Griffith for Best Actress. Sadly for Griffith, she lost to another silent screen biggie: Mary Pickford.

Besides Griffith’s nomination, The Divine Lady stood out for another reason—and it was for something that would change films forever.

18. There Was A Change Coming

Griffith’s The Divine Lady was one of the first films to have more than just a soundtrack. The film came to life with both singing and sound effects—this was something completely new for audiences. It seemed, at this point, inevitable that films with spoken dialogue were just around the corner. Griffith had a legitimate concern: how would her voice sound on film?

19. She Feared The Worst

Before Griffith allowed her voice to be in a film, she took some pretty serious precautions. She convinced the studio to make her transition to the talkies relatively risk free. In 1929, Griffith got an insurance policy not on her life, but on her voice. The studio took out the policy for one million dollars. There wasn’t, however, enough insurance in the world that would protect Griffith from what would happen next.

20. She Dove In

Talkies were making a big splash with the movie-going public, and Griffith had no choice but to dive in. Her first talkie was 1930’s Lilies of the Field, which was a remake of one of her previous silent films. Of course, audiences were dying to hear what Griffith sounded like—and then they were dying for her to be silent. The truth was devastating: the most beautiful actress in the world didn’t have the most beautiful voice.

21. It All Came Crumbling Down

When audiences first heard Griffith’s voice, they were in for a shock. She didn’t sound good at all. One critic said that Griffith “talked through her nose”. This fact did not do any favors for the film, which ended up being a box office flop. Griffith had been in flops before, but this was different. She got it that audiences didn’t want to hear her voice, but the talkies were here to stay.

Her entire career was about to come crumbling down and there wasn’t much she could do about it.

22. She Faced It Alone

Griffith still had a couple of films left in her, but the writing was on the wall: She didn’t have a voice for the talkies. There are horror stories out there about silent stars who descended into a life of poverty after the advent of the talkies—and it looked like Griffith was going to be heading down that road as well. In 1934, Griffith officially retired from show business and at the same time, divorced her husband.

She was going to face the end of her career very much alone. But what was her plan?

23. She Joined The Team

The first part of Griffith’s plan was to marry someone rich. Enter George Preston Marshall—you know someone’s got money when they use three names. Well, Marshall owned the Washington Redskins—now called the Washington Commanders—an NFL team. Marshall became famous for a seriously disturbing reason. He refused to have black players on his team.

It's not clear what Griffith thought of Marshall’s prejudice, but she did find time to write their fight song: Hail to the Redskins. Griffith, however, had more plans in store for her husband’s football team.

24. She Changed Football

Griffith saw an opportunity in her husband’s business: why not bring a little show business to the football field. In addition to writing the team’s song, she also designed the team’s uniforms. Next, she got her husband to hire a band consisting of 55 musicians to play before the games, and a swing band to provide music during the games. Adding music to the game, however, wasn't quite enough for Griffith: she needed drama.

25. She Wasn’t Woke

If you came to a Washington Redskins game during this time, you were in for more than just a game. At half time, a 93 piece band came out dressed head to toe in Indian dress. This was long before the time of political correctness, and the audiences lapped it up. Also on the field was a huge teepee that periodically erupted in smoke. In the distance audiences could hear the pounding of tom-tom.

Once Griffith had transformed her husband’s football team, she decided it was time to transform lives.

26. They Disappeared

In 1941, Griffith decided that she wanted to be a mother. She and her husband adopted two girls, Cynthia and Pamela. Griffith talked about the girls in a Los Angeles Times feature about her life. But afterward, a strange mystery popped up. Eerily, after that article there was no other mention of Cynthia and Pamela in any other press. In fact, reporters didn’t even write about them in Griffith’s obituaries.

It was like the girls vanished into thin air. Did these two young girls even exist? Or was it another mystery attached to the name of Corinne Griffith?

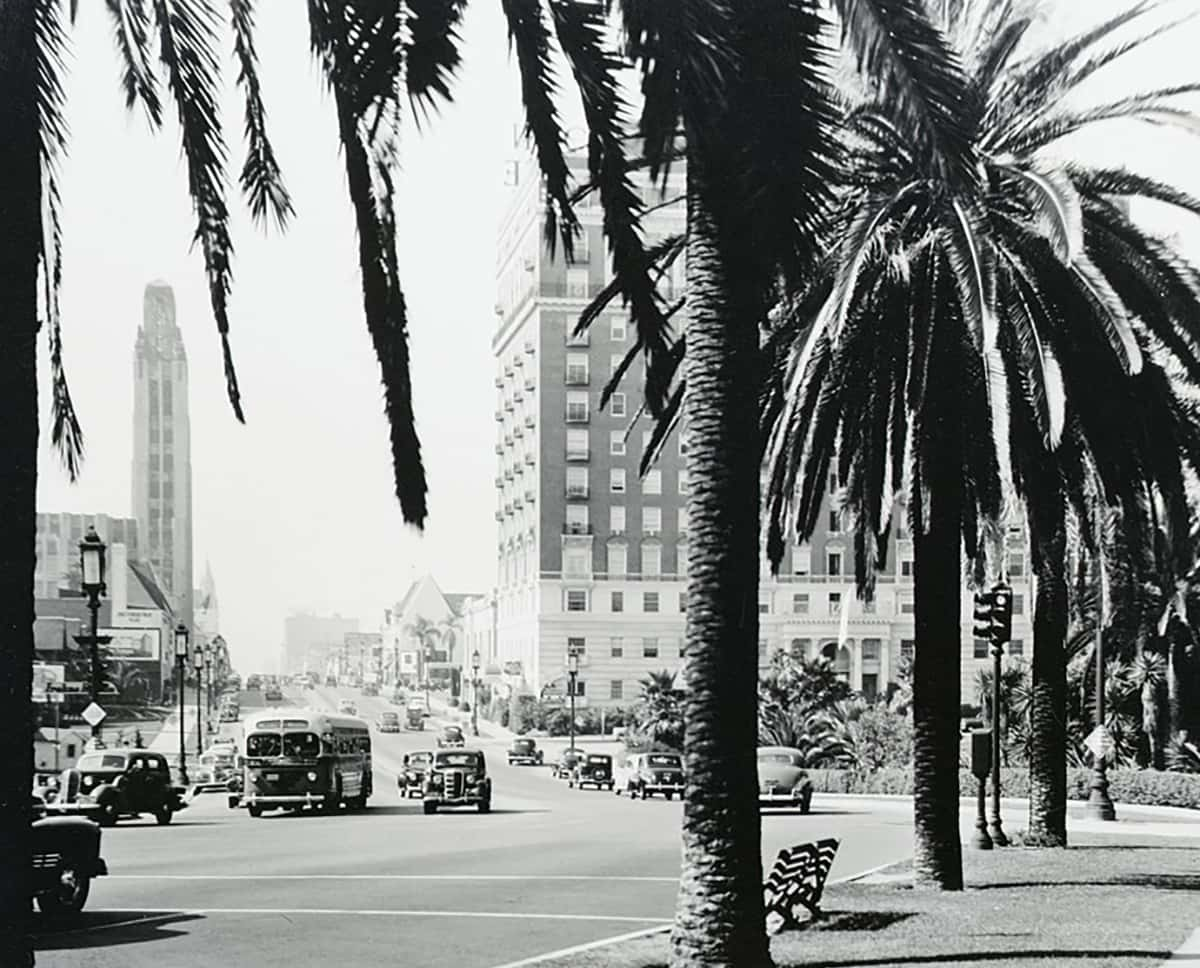

27. She Took A Corner

Griffith was not one to just live off the wealth of her husband. So, even though her plan had been to marry someone rich, she still wanted to be independently wealthy. With the cash she made making films, Griffith continued investing in real estate. She had her eye on Los Angeles, and on one corner in particular: Wilshire Boulevard and South Beverly Drive.

Griffith wasn’t one to go small. She wanted four buildings: one on each corner of the intersection. Oh, and she wanted each one named after her.

28. She Saw Red

Griffith was quickly amassing quite a fortune—and it was very much independent of her husband’s money. As she started counting her bundles of cash, she noticed something: the government had taken a rather large chunk of change—calling it tax. Griffith saw red at the amount that the government had taken. This caused Griffith to sit down and do the only thing she could to vent her anger: write speeches.

29. She Had A Bee In Her Bonnet

Griffith used the speeches she’d written against income tax—and the 16th amendment that allowed it—and started trying to convert Americans to say no to income tax. She was absolutely certain that most of the taxes Americans paid went to corruption within the government. In the end, she gave close to 500 speeches against income tax.

Griffith had another pet peeve she liked to talk about—and it was one even closer to her heart.

30. She Was Ahead Of Her Time

Griffith firmly believed that women should not be dependent on men for money. She was very proud of the fortune that she had amassed without the help of a man. She said that women would get more respect from their husbands if they had their own money. Griffith really hated the tricks wives had to play in order to get the cash they needed and wanted. She certainly was a woman ahead of her time.

Griffith had a lot to say, she just needed a way to get her message out to Americans.

31. She Found A New Career

Once Griffith had found success in Hollywood as both an actor and a real estate mogul, she turned her attention to something else: writing. Griffith wrote 11 books, two of which became bestsellers. Griffith’s memoir about growing up in Texarkana became a feature film in 1962 called Papa’s Delicate Condition. The film starred Jackie Gleason as Griffith’s very eccentric father.

Griffith's career was again flourishing. Her marriage? Not so much.

32. He Didn’t Have A Plan

By 1958, Griffith was having trouble with husband number three. Remember, he was the football team owner named Marshall. Griffith had concocted a nickname for him: “The Marshall without a plan.” This was a reference to the US plan—thought up by George C Marshall—to help Europe financially after WWII. She was openly ridiculing her husband and soon sent him packing.

Griffith suddenly had oodles of time on her hands, and it sent her to a very familiar place.

33. She Made A Comeback

For some reason, Griffith came out of retirement and made a film in 1962. It was Paradise Alley and it was not at all related to Sylvester Stallone’s movie of the same name. It did, however, feature more than a few stars from the silent film era, which may have been why Griffith left retirement to appear in it. The film had a very small release and barely made a ripple in Hollywood.

While this film didn’t make much noise in Hollywood, Griffith's next marriage certainly would.

34. She Went For Younger

Being one of the richest women in America, Griffith took a page from the rich men’s playbook and took a younger lover. Danny Scholl, an actor in musicals, was just 44 years old—which was 25 years younger than Griffith. She was certainly living the life. She had a fortune in real estate and a young man at her side. One thing that Griffith hadn’t learned from her male counterparts was that she didn’t have to actually marry her young fling.

In 1965 Griffith did just that, and the results were catastrophic.

35. She Wanted Out

Griffith soon realized she’d made a mistake marrying Scholl. Some reports say it was only days after the wedding when Griffith realized she wanted out. Her first plan was to get the marriage annulled. The judge gave Griffith a hard no, so Griffith made a stunning declaration. The marriage didn’t count because she and Scholl had never been intimate. This didn’t sway the judge one bit. It was going to be a divorce, and it was going to get messy.

36. She Had To Pay

While waiting for the divorce trial to begin, the judge told Griffith that she had to pay Scholl $200 every month in alimony. Griffith was experiencing what so many rich men have to go through: paying for their indiscretions. You can imagine how Griffith, who was so strongly against income tax, felt about alimony. Obviously, she would do anything to make these payments stop.

37. She Made Jaws Drop

It wasn’t until 1966 that the divorce trial began—so Griffith had already paid Scholl a big chunk of change. She was beside herself with anger, but she had a bizarre plan to get rid of Scholl for good. She wasn’t going to hire a hitman, that was far too dangerous. Instead, she approached the judge at the divorce court and said these jaw-dropping words: “I am not Corinne Griffith.”

38. She Didn’t Exist

If this wasn’t Corinne Griffith, who was the woman standing in the courtroom? The mystery woman told the courtroom that Corrine Griffith had passed and that she was actually Augusta Griffin—Griffith’s younger sister. The stunned courtroom wanted to know how this was possible. The woman claiming to be Augusta Griffin told the courtroom that she had replaced her sister when Griffith had died in 1924.

39. She Didn’t Know

Whoever it was in the courtroom—Griffith or Griffin—told the judge something else earth-shattering. She had never married her two previous husbands. When the judge asked Griffith what her age was, she simply said she didn’t know. She claimed that she hadn’t kept track of her age since she was 13 years old. Besides that, she added, her religion—Christian Science—would not let her state her true age.

Griffith was one of three things: crazy, trying to confuse the judge…or she really was her sister.

40. They Disagreed

The courtroom had descended into mass confusion. The judge had no idea who was standing there making these claims. Was it Corinne Griffith or her sister? The courtroom then heard from two of Griffith’s friends: surely they could clear up this confusion. Betty Blythe and Claire Windsor, both actors, got up on the stand. There was a hush as the ladies prepared to speak: they both disagreed with her, and stated that this certainly was Corinne Griffith.

41. She Changed Her Story

In spite of what her friends said, Griffith stood by her story in court. It was only later, when talking to reporters, that she changed it. The weird thing is that the new story was even more unbelievable than the first one. Maybe Griffith realized that she couldn’t pass for her much younger sister, so she created another sister—one exactly her age. Suddenly Griffith was her twin sister Mary, and a new narrative was hatched.

She said it all started in Mexico…and the story was a doozy.

42. He Was Desperate

Griffith told reporters that Corinne Griffith had been working in Mexico on a film. While on location, Griffith fell ill with a local disease and died. The director of the film, Adolph Zukor, was desperate to finish the film and didn’t know what to do. Somehow, Zukor found out that Griffith had a twin sister and contacted her immediately.

43. He Made Her An Offer

“Mary” Griffith had no idea her sister had died when she got the call from Zukor. Of course, when he told her the sad news, Mary was distraught and couldn’t stop crying. Only once she stopped sobbing could she listen to Zukor’s plan. He said that Mary could replace Corinne and no one would know the difference. Mary didn’t know what to say: She couldn’t replace her sister, she didn’t even know how to act.

And then, Zukor made her an offer she found impossible to refuse.

44. She Made A Decision

Zukor offered Mary Griffin one million dollars if she replaced her sister in the movie he was making in Mexico. Mary was still upset from hearing of her twin sister’s demise, but she started to listen to reason. It was a lot of money, and it would be what Corinne Griffith would have wanted. She told the director she’d come to Mexico and finish Griffith’s film.

The only problem was: once she’d starred in a film she got the taste of being famous. This led to Mary Griffin making a scandalous decision.

45. She Took Over

Mary Griffin decided, after replacing her sister in one film, to take over her sister’s life. This is what led to her jaw-dropping admission at the divorce proceedings of Corinne Griffith and Danny Scholl. It was a bizarre confession and it was, very likely, all a bunch of lies. Griffith was doing whatever she could to avoid paying alimony to her economically disabled ex-husband.

The judge, in the end, didn’t make Griffith pay alimony, but she was left with Scholl’s lawyer’s fees to pay. You could say they robbed her blind, but that was actually coming up next.

Getty Images Electric Club luncheon, 29 September 1952. Corinne Griffith. (Photo by Los Angeles Examiner/USC Libraries/Corbis via Getty Images)

Getty Images Electric Club luncheon, 29 September 1952. Corinne Griffith. (Photo by Los Angeles Examiner/USC Libraries/Corbis via Getty Images)

46. They Wanted Her Jewels

Griffith’s divorce and strange testimony was actually just the start of the nightmare. In 1966, Griffith suffered a home invasion. Thieves entered her house and demanded her valuables. Griffith, never one to let a man intimidate her, refused to open the case where she kept her jewelry. The thieves had to think fast to find a way to get her to unlock the case. Well, what they came up with was brutal.

47. They Threatened Them

Two thieves had entered Griffth’s home and were itching to get their hands on her valuable jewelry collection. When they saw that Griffith was not about to budge and open her jewelry box, they took her servants and threatened their lives. Griffith had no choice but to comply. Her $100,000 trove of gems and jewels were certainly not worth a human life.

The thieves had certainly underestimated Griffith’s character, but it turned out that most everyone had.

48. She Wasn’t What She Seemed

Throughout her life, Griffith was quite outspoken on many topics. Her private life, however, was something quite different. You’d think that someone who made protest speeches, wrote angry letters and worked in show business would have a few vices. But no, Griffith’s friends reported that she was quite demure and prim. She did not approve of people who smoked or swore—as she did neither of these. Her prim character even got her a nickname: the Orchid Lady.

49. No One Noticed

In July 1979, Griffith suffered a stroke. They took her to Saint John’s Hospital where she quietly died on July 13, 1979. It seemed her passing was a little too quiet—no one seemed to notice. She was a major Hollywood star, an author, and was, at one time, one of the richest women in the world. Given her celebrity, the two weeks it took for the Daily Variety to print the news of her passing seemed excessive.

Getty Images Federal tax talk, 16 July 1956. T Coleman Andrews;Corinne Griffith;Jack Matthess.;Caption slip reads: 'Photographer: Mack. Date: 1956-07-16. Reporter: Adler. Assignment: Federal tax talk. 27: L to R T Coleman Andrews, Corinne Griffith & Jack Matthess, pres. of Bev Hills Rotary Club. 25/26: T Coleman Andrews, former commissioner of internal revenue'.. (Photo by Los Angeles Examiner/USC Libraries/Corbis via Getty Images)

Getty Images Federal tax talk, 16 July 1956. T Coleman Andrews;Corinne Griffith;Jack Matthess.;Caption slip reads: 'Photographer: Mack. Date: 1956-07-16. Reporter: Adler. Assignment: Federal tax talk. 27: L to R T Coleman Andrews, Corinne Griffith & Jack Matthess, pres. of Bev Hills Rotary Club. 25/26: T Coleman Andrews, former commissioner of internal revenue'.. (Photo by Los Angeles Examiner/USC Libraries/Corbis via Getty Images)

50. Her Story Got Told

In 1978, Sunset Boulevard director Billy Wilder made a film called Fedora. This was a fictional tale of an aging silent screen star who gets her daughter to impersonate her so she can watch her life continue on with youthful beauty. The movie got its plot from a book by Tom Tryon who did not hesitate to state the source material for his story: He got the idea after reading about Corinne Griffith and her attempt to impersonate her sister.

Sources: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20