We use it as a derogatory phrase now, but once upon a time, snake oil did actually work as a topical medicine! But it was rare and expensive, and some greedy folks saw an opportunity. These charlatans peddled so-called cures with ingredients that ranged from useless to addictive to downright dangerous. Here are devious facts about medical history's most dangerous crooks.

Medical Crooks Facts

1. Paging Dr. Black

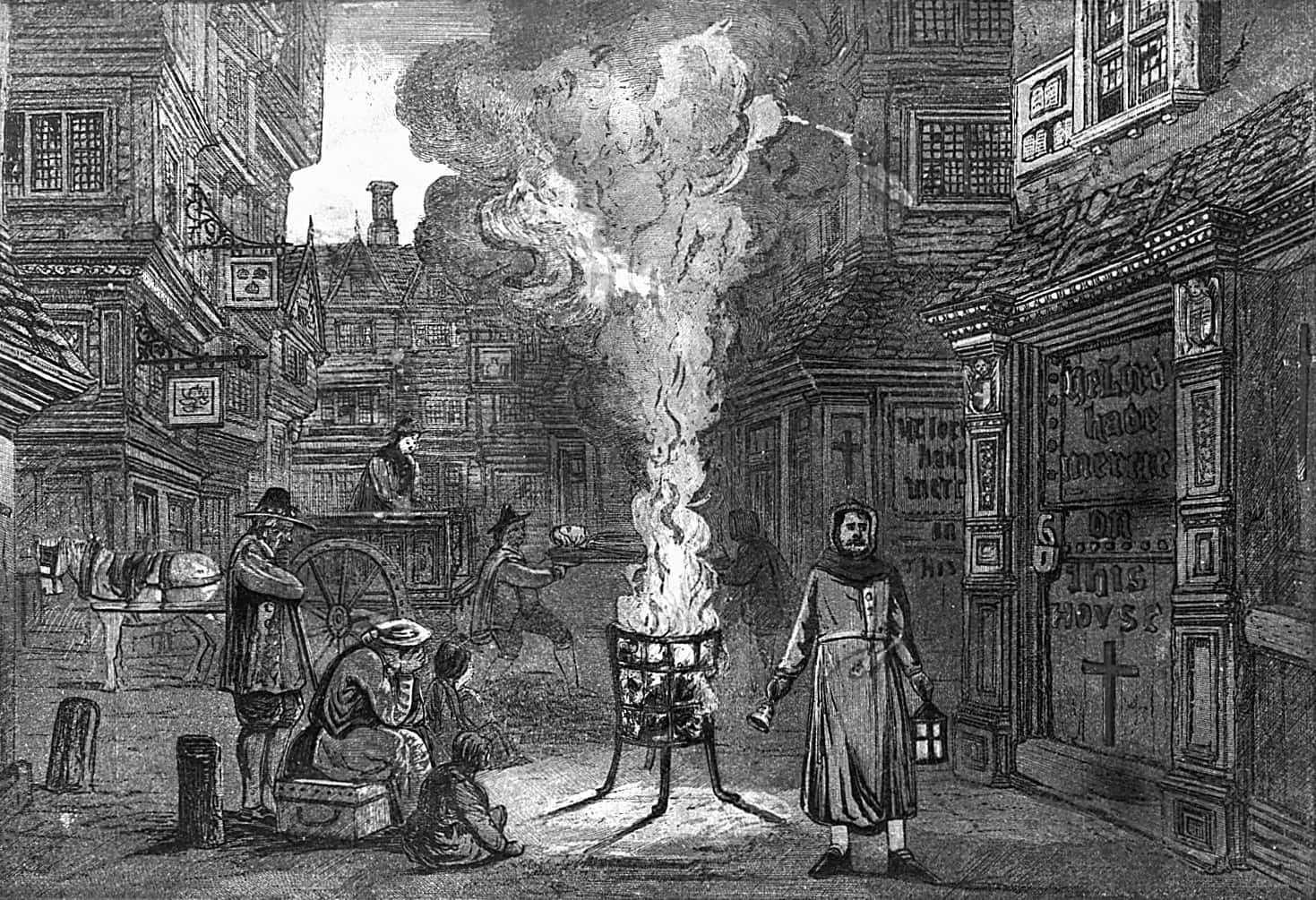

From its first recorded outbreak in 1348, The Black Plague claimed an estimated 150 million lives. Doctors called upon to treat symptoms knew as little about the rapidly spreading disease as its victims, and so-called treatments were absurd. Think an onion butter poultice or a sprinkling of dried frog powder was going to do the trick?

Bloodletting, arsenic, and floral compounds were equally useless.

2. Easy Bake Oven

Being a doctor during the Middle Ages in Europe was both thankless and dangerous, especially when the plague broke out. Most “physicians” had little to no training—but that didn’t stop them from charging extra fees to desperate families and getting terribly creative with their so-called cures. There are actual accounts of plague sufferers close to death being coated in mercury and baked in an oven to try and force out the illness.

3. Turning the Tables

Although some plague doctors were charlatans taking bribes from desperate families, others served as record-keepers of the dead and dying. Whether scheming or well-intentioned, plague doctors were often respected for their bravery. They were also seen as worthy enough to be kidnapped for ransom by scheming members of the public.

4. Doctor Feelgood

In the early nineteenth century—when society mistakenly assumed that females had no libido—women paid doctors for genital massages to relieve “hysteria.” A diagnosis of hysteria was often given to otherwise healthy women who complained of anxiousness, irritability, or insomnia. The genital massage—which generally resulted in orgasm, but which they called “paroxysm” back then—was a much-hyped “miracle cure,” and many doctors profited handsomely off it.

5. Say Hello to My Little Friend

Dr. Joseph Mortimer Granville is the 19th-century physician who invented the “electromechanical medical instrument,” AKA the first vibrator. Granville’s contraption was an instant hit with mothers seeking a little “hysteria” helper. Mail-order versions of the instrument were called “manipulators,” or “personal massagers.”

6. Ah, the Joys of Repression

For every 19th-century damsel in distress over hysteria, there seemed to be equal numbers of desperate men who were suffering from low libido and impotence, with no clue about how to “turn it on.” The act of self-pleasure had been demonized in society, which opened the bedroom door to unscrupulous businessmen and frauds.

7. Our Love’s Electric

Claiming to cure “nervous exhaustion” (impotence) and tossing in backache or kidney problem cures to appear discreet, newspaper ads gloried the use of mail-order electric belts that were supposed to shock the monkey back into fighting form. Many a quick buck was made off the zapped members of gullible gentlemen.

8. When Pigs Fly

In 1899, a medicine-show con artist named W.I. Swain was arrested. Twice. Traveling through Indiana, he kept on swindling the public without a license, and authorities were not having it. What was he selling? Capsules that contained fake tapeworms, so people could eat “endlessly” and not gain weight.

He claimed that the fake tapeworms would “navigate the digestive system,” and when they “emerged” from the body, it would prove that his medicines were real. Swain somehow managed to acquit himself of all charges, but he’s still a swine to us.

9. Travelin’ Man

Patent medicine peddling throughout America became an entertainment spectacle. Dudes in gaudily-decorated wagons traveled through 19th-century towns, putting on “medicine shows” and selling cure-alls—mostly spirits, AKA an alcohol-based solution—masked in thick, dark-colored bottles.

But just who bought these spirits? The answer is absolutely hilarious...

10. Temperance Ladies Feeling Fine

A humorous fact from the patent medicine hype of the 19th century was that many women of the temperance movement enthusiastically endorsed these “cures” for their “unmentionable female disorders.” The tonics mostly contained sweet cherry juice for flavor—and alcohol or opiates for effect. Nothing was cured, but the potent tonics sure made those teetotaling temperance ladies feel 100 proof better!

11. Monkey See, Monkey Do

During the roaring 20s and the dirty 30s, a Russian surgeon named Serge Abrahamovitch Voronoff was the talk of Paris for his technique of grafting monkey testicle tissue onto men’s testicles for “therapeutic” purposes. Voronoff had already gotten rich from his other medical schemes, including the implanting of monkey glands into people, but this monkey-junk quackery was next level.

His firmly held beliefs were eventually discredited by other scientists, and Voronoff became vilified in France.

12. Coke Was the Real Thing

In the late 1800s, scientists discovered a new, relatively cheap stimulant called Erthroxlyn coca, which was derived from the coca leaf—yup, the invention of coke. While it was reasonably effective as a topical anesthetic during minor medical procedures, drug manufacturers took its stimulating qualities right to the bank.

Tonics, powders, lozenges, and cigarettes got loaded up with the stuff. It was even featured in the Sears catalog!

13. Cause and Effect

Coke products in the 1800s supposedly cured depression, lethargy, impotence, toothaches, and most misleading of all—alcoholism. Boxes of tablets were 50 cents and were said to relieve hay fever, nervousness, insomnia, and headaches. Of course, it was later proven to cause insomnia, depression, digestive issues, and delusions.

14. Kids, Don’t Eat Your Veggies

Perry Davis was a shoemaker in the 1800s, and he should have stuck to cobbling. He took up patent medicine quackery as a side hustle, including a supposed cure for cholera. He advertised his formula as being “purely vegetable,” and a tonic that “no family should be without…” but he never revealed that the tonic was purely opium.

15. Like a Yorkshire Cowboy

From 1887 to 1890, one Yorkshire dude brought the Wild West-style circus to Britain. William Henry Hartley styled himself as Britain’s Buffalo Bill, and he called his traveling medical circus the Sequah Medicine Company. Hartley always started his shows after dark, and he told his brass band to drown out the shrieks of “clients” getting their teeth pulled.

16. The Devil Made Me Do It

To add an extra layer of unorthodox weirdness to it all, Hartley also sometimes held séances. All of this spectacle was done to peddle his Prairie Flower and “Indian oil,” a mixture that Hartley swore would cure stomach issues and liver disorders. His cure was later found to be low quality fish oil cut with turpentine.

17. The Wright Stuff

In the 1870s, a chemical researcher named C.R. Alder Wright created a new drug called diamorphine as an alternative to morphine. In 1895, some super-sleuth working at Bayer pharmaceuticals uncovered Wright’s research. In a short time, dope products started popping up everywhere.

18. Big Bad Bayer

By 1898, Bayer was pumping out aspirin laced with dope. They marketed the aspirin to parents as being kid-friendly, with ads featuring kids begging for the medicine, and moms spoon-feeding it to them.

19. Party’s Over, Pushers

As the 20th century dawned, negative publicity and scientific warnings about addiction couldn’t be ignored. But Bayer pharmaceuticals kept on pushing dope-laced aspirin until 1913. The FDA finally banned it entirely in 1924.

20. Knocked Up?

In the late 19th century, over 12,000 pregnant British women are thought to have been duped by the horrifically unscrupulous Chrimes brothers. The Chrimes had started placing anonymous ads in UK newspapers heralding “Lady Montrose’s Miraculous Female Medicinal Tabules,” with promises to cure women of their “Obstinate Obstructions.”

It was basically advertising an abortion pill, although abortions were officially outlawed back then.

21. Failure Was the Only Option

Thousands of women mailed their shillings into the Chrimes brothers for a box of Lady Montrose’s Miraculous Female Medicinal Tabules, confident in a written guarantee that “failure is absolutely impossible.” Of course, the three Chrimes brothers were operating under aliases, and the pills were utterly useless.

22. The Shamelessness Continues

The Chrimes brothers were utterly shameless. They grew Lady Montrose’s Miraculous Female Medicinal Tabules into a multi-layered scam, utilizing different London addresses to send an additional letter to the gullible women who’d purchased the tablets.

23. The Other Blue Pill

Women who’d purchased the Lady Montrose tablets were shocked to receive a mysterious letter from a second London address, with a strongly worded suggestion to purchase “Panolia Electric Blue Pills,” for considerably more money. The “extra strength” blue pill cost five times as much as the Lady Montrose tablets.

24. Anonymously Yours

The offer to purchase the Panolia Electric Blue Pills was the next level in the Chrimes brothers’ scam. The mysterious letter claimed to be from an anonymous female, warning fellow females that the Lady Montrose tablets were not effective. But the letter proclaimed that the blue pills were so powerful, they couldn’t be advertised for fear of prosecution.

25. Layering the Blackmail on Thick

Talk about putting the “crime” in Chrimes. In 1898, the Chrimes brothers topped off their scheme by launching their blackmailing careers. They hired a clerk, rented offices under an assumed name, bought a whack of stamps, and meticulously mailed an official-looking letter en masse to thousands of women who’d purchased the Lady Montrose tablets, or the Panolia blue pills.

The letter threatened to expose any woman who’d attempted abortion, instructing them to pay up or face immediate imprisonment.

26. Boo-Yah, Jerks

The scale of planning in the Chrimes blackmail scheme was mind-boggling, but the husband of a targeted woman suspected it immediately. Finding the Chrimes brothers was more difficult. It took considerable manpower and sleuthing skills by Scotland Yard to finally nab them. The trial of the Chrimes brothers was sensational, although many details of the proceedings were deemed unfit to print due to their “feminine nature.”

In the end, Edward and Richard Chrimes were sentenced to 12 years imprisonment in HM Parkhurst Prison, a wretched correctional center on the Isle of Wight. Younger brother Leonard received just seven years because of his age.

27. Risky Business

The Chrimes brothers even risked some sleazy side hustles. Assuming the alias of the “Bradbury Brothers,” they sold “Hare’s Soap,” or hair soap. Their con was a newspaper ad with a fake contest, and bogus cash prize. Anyone who’d purchased the soap was eligible to enter, but the con failed when a British newspaper wrote that it was a swindle.

28. Here a Quack, There a Quack

Thankfully, as the 20th century dawned, authorities began coming down hard on quacks. In 1906, the Bureau of Chemistry (now the FDA) published the Pure Food and Drug Act, focusing on the prosecution of fake patent medicines and false claims. At the same time, the American Medical Association (AMA) conducted thorough, anti-quack investigations, distributing anti-quackery reading material to the public through books and pamphlets.

29. Wash That Mouth Out With Soap

Anti-quackery enforcers in the early 20th century shut down plenty of bogus medicinal products like “Fatoff.” Advertised as a “weight-loss cure,” Fatoff was nothing more than 10% soap and 90% water. Another fake obesity cure called “Human-Ease” contained 95% fatty lard!

30. The Real Deal

Unlike all these fake cures, Chinese water-snake oil really is an anti-inflammatory. In the 1800s, when the Transcontinental Railroad was being built, indentured Chinese laborers were hired as a cheap alternative to white American workers. The Chinese used their centuries-old remedies, notably Chinese water snake oil, to relieve joint pain, arthritis, and bursitis—and the Americans who tried it were amazed.

31. Snake Oil Goes Gangster

19th-century hype spread through the US about the miraculous powers of Chinese water snake oil. Some entrepreneurial—and unscrupulous—Americans figured it’d be a cinch to use rattlesnake fat instead of Chinese water snakes. There was just one problem: rattlesnake fat isn't an anti-inflammatory. But Clark Stanley didn't let that stop him!

32. A Rattlesnake King Is Crowned

In 1893, a former cowboy named Clark Stanley became the bombastic face of snake oil salesmen when he jumped onstage at the World’s Exposition in Chicago. He freaked out the crowd by slicing open a live snake and claiming that Hopi medicine men had taught him to heal ailments with rattlesnake oil.

33. A Literal Cure-All

Clark Stanley claimed his “Snake Oil Liniment was “good for man or beast,” and a cure-all for everything from rheumatism, “lame back,” sciatica, “contracted chords,” frostbites, bruises, sore throat, and “bites of animals, insects, and reptiles.” His gaudy newspaper ads claimed that his product was “good for everything that a liniment ought to be good for.”

34. Stanley’s Steamer

Clark Stanley swindled consumers with his Stanley’s Snake Oil for nearly two decades. In 1917, federal investigators seized the product for analysis. It was nothing but beef fat, turpentine, and red pepper, with no snake oil in it. The fallout from Clark Stanley’s snake oil swindle forever tied the saying “snake oil” with fraud.

35. The Snake Didn't Bite Back

Federal investigators fined Clark Stanley $20 for "misbranding" his product by "falsely and fraudulently represent[ing] it as a remedy for all pain." Stanley never defended the charges.

36. Crocodile Hunters

In 1600 BC, ancient Egyptians were convinced that evil spells caused impotence in men. Ancient Egyptian witchdoctors peddled many cures to men inflicted with the “spell,” including rubbing ground-up baby crocodile hearts all over their manhood. Crikey, mate!

37. Stay Thirsty My Friends

Curing erectile dysfunction with ground-up baby crocodile hearts is laughable, but it just might beat the alternative—some Egyptian witchdoctors told men to drink their urine as an impotence cure.

38. Wait! It’s a Pink Pill

In the 19th century, “Dr. Williams' Pink Pills for Pale People” was supposedly just the ticket for anemia. The pink pills were largely iron oxide and magnesium sulfate—thankfully, among the least dangerous, non-addictive patent meds ever peddled. But George Fulford, the guy peddling those pills, still met a terrible fate.

Fulford’s automobile collided with a streetcar in 1905. His death marked the first automobile casualty in Canada’s history.

39. Fake Magic

The patent medicine peddlers labeled their bottles with pictures of Native Americans and mystical-sounding names, implying a magical cure.

40. Bringing Sexy Back

Patent medicine hustlers sold “Egyptian Regulator Tea” to girls who “lacked appeal.” I’m sure Cleopatra swore by the stuff.

41. Burn Baby Burn

“Rengo Medicine” was a type of formula sold by patent medicine hustlers to men who wanted to “turn fat into muscle.” I doubt they burned calories, only holes in their wallets.

42. Feed Those Girls

Patent medicine hustlers touted a “full, rounded bosom” to any woman who bought “LaDores Bust Food.” I thought that was my stomach rumbling.

43. A Radiating Lunatic

One nutjob wasn’t just the president of a company peddling quack—he was a client too. William John Aloysius Bailey claimed to be a certified medical doctor, but he was just a Harvard dropout. Bailey swore that radioactive radium was a cure-all for common ailments, and he peddled numerous patent medicine inventions loaded up with lethal amounts of radiation.

44. A Word for the Dying

One of Bailey’s most lethal inventions was Radithor, otherwise known as the “best example of radioactive quackery.” Bailey swore on it as “A Cure for the Living Dead,” as well as “Perpetual Sunshine.” Death is a perpetual cure to being part of the “living dead,” I’ll give him that.

45. The All-American Victim

Sadly, many clients bought into Bailey’s radioactive quackery and suffered the worst fate as a result. Eben Byers was an American golden boy—a celebrated socialite, industrialist, and athlete who won the US Amateur golf tournament in 1906. But in 1927, tragedy struck. He injured his arm in a train accident and needed medication for the chronic pain. Byers didn't know it at the time, but his "cure" was actually a curse.

46. Eben’s End

Byers began to drink Bailey's Radithor obsessively, saying it made him feel better. The poor man drank almost 1,400 bottles of the poinson in his lifetime. He was eventually forced to have his jaw removed after he became infested with bone cancer. The one-time American boy died in 1932, a mere five years after his first dose of Radithor.

47. Cause of Death

On May 17, 1949, Bailey's years of medical quackery finally caught up with him when the man died of bladder cancer. 20 years later, authorities exhumed his body. Unsurprisingly, they found it to be "ravaged by radiation."

48. Don’t Bess on It

Queen Elizabeth I was a historical force to be reckoned with, but her vanity and insecurity also got her into deadly trouble. She used a product called Venetian ceruse to whiten her face dramatically, and mercuric sulfide to fake a blush on her cheeks. The Venetian ceruse was a combination of vinegar and lead—and the ingredients in the blush are lethally obvious.

Although Bess was fooled into thinking that makeup caked all over her face would hide her smallpox scars and make her look more attractive, it poisoned her over time and ruined her skin more.

49. That Water Was Un-Everything

There’s undrinkable water, and then there was Solomon’s Water. After Elizabeth I died, discreet reports trickled out to the masses about her ravaged skin, with her makeup being blamed. But fashionable women of the period continued to be duped by cosmetic-peddling quacks for centuries, and Solomon’s Water was one of the worst.

50. Don't Drink the Water

Women were made to believe that Solomon’s Water cured everything: smallpox scars, moles, warts, zits—even harmless freckles. If it did appear to “cure” those skin conditions, it was only because the mercury in the formula was stripping the skin off the face, eating into the flesh, and eventually causing receding gums in many users, which made their teeth fall out.

Sources: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19