Charlie Parker developed bebop and changed jazz music forever, but even though he blew a horn, he lived like a rockstar. Famed for his unparalleled musical improvisation and breakneck tempo, he hit all of the high and low notes—both on stage and in life. Bird's genius burned bright; it was only a matter of time before he went up in flames.

1. He Had A Melodious Beginning

Charlie Parker was born in Kansas City, Kansas in August 1920. His father was performer Charles Parker, whom The New Yorker described as a “knockabout vaudevillian.” His mother was a local woman named Adelaide “Addie” Bailey. With this small family, the first few years of Parker's life were relatively harmonious. But it wouldn't stay that way for long.

2. He Hopped Across The River

When he was just seven or eight years old, Parker hopped across the Missouri River to the Missouri side of Kansas City. That’s about the same time that his father hopped on a Pullman train car and right out of his life. Parker Sr. traveled for work often, leaving young Parker Jr. to fend for himself and find his own way.

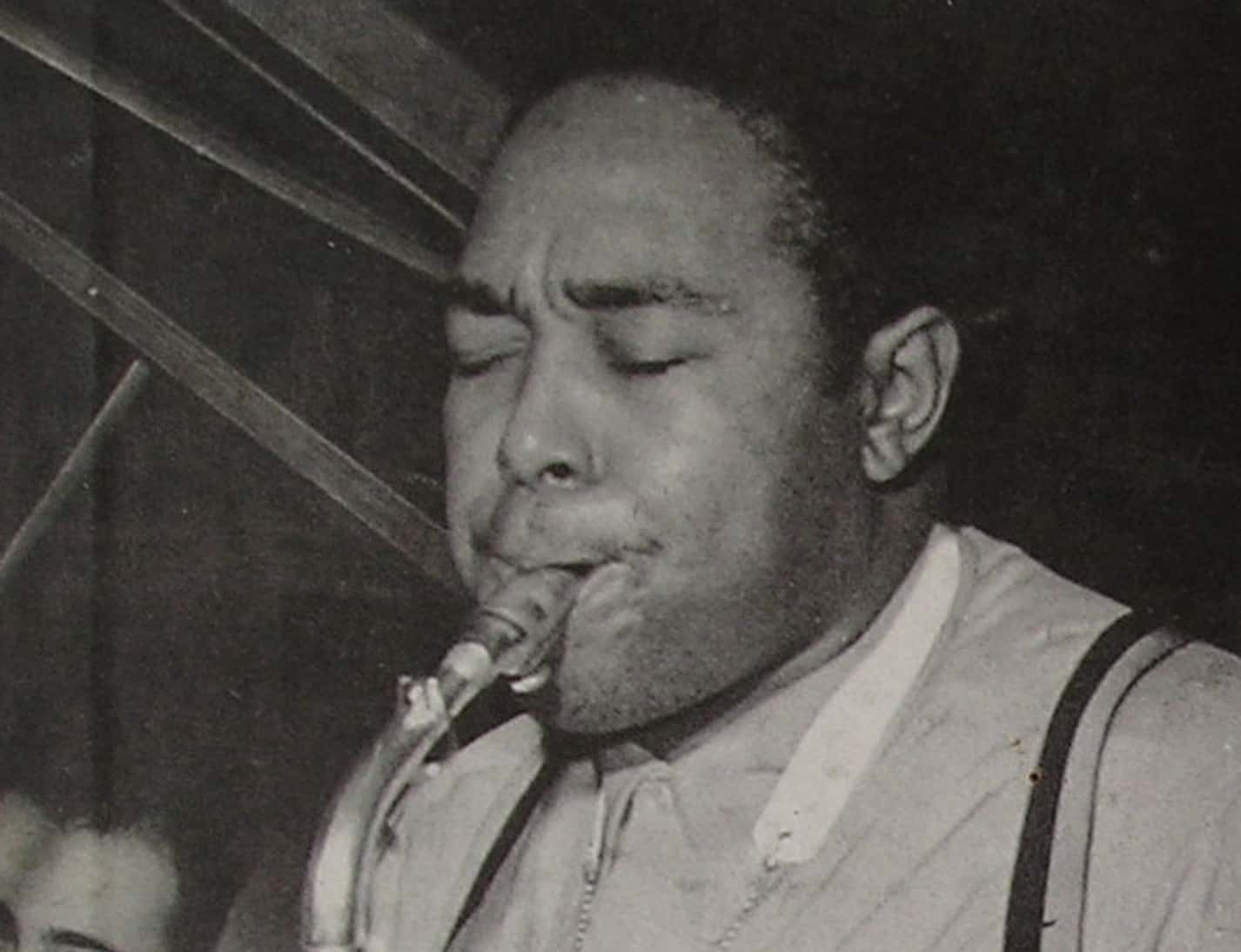

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

3. He Had To Learn To Play Solo

With his largely absent father, Parker poured his sorrows into music. While his father traveled for work, he picked up the saxophone and started playing in the band at Lincoln High School. After just three years, however, he decided that it was time to play solo. He dropped out of high school and set out on his own at just 15 years old. That’s also when he started improvising. Well, more like spiraling out of control.

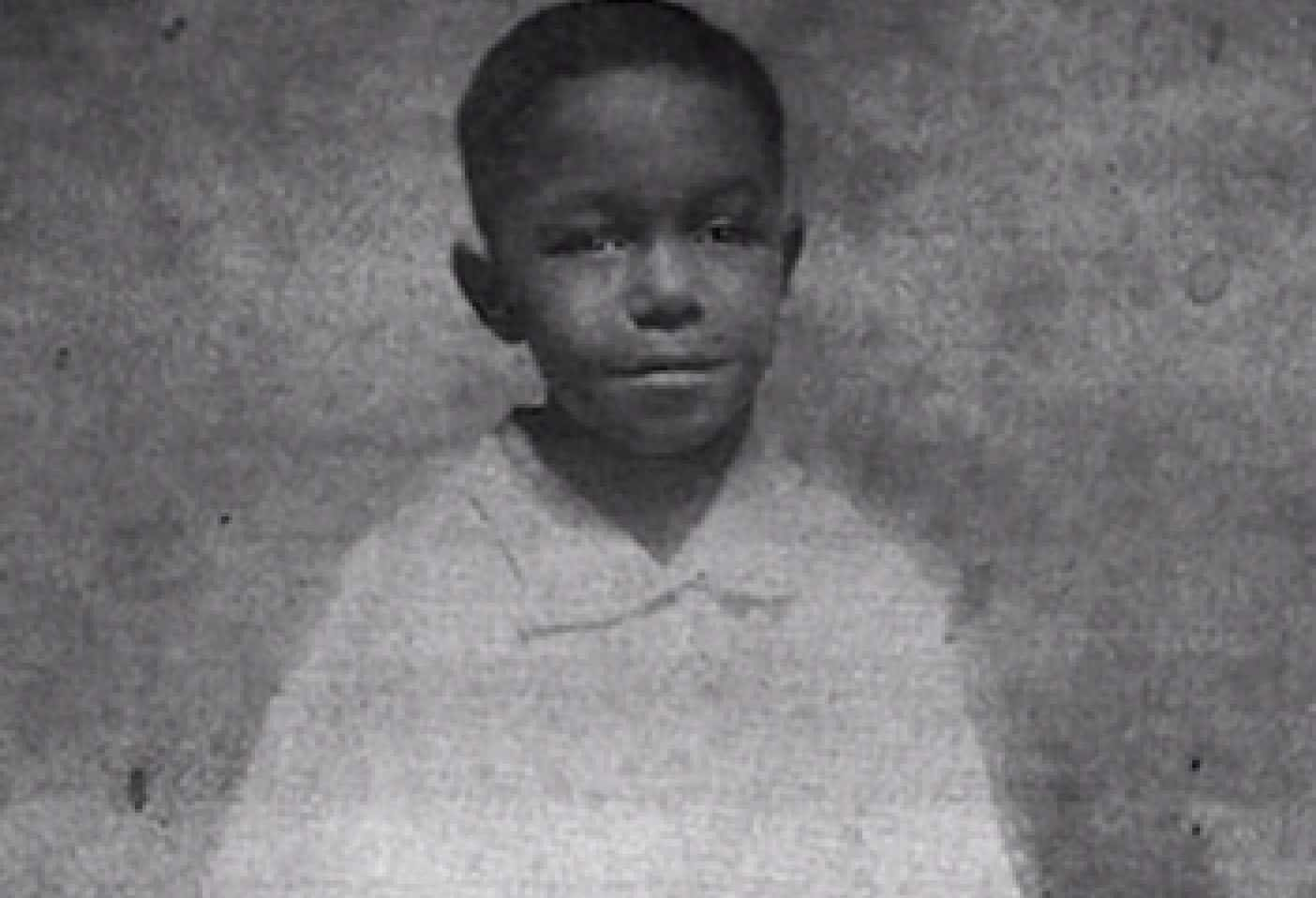

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

4. He Was A Young Father

At just 16 years of age, Parker was already starting to live life in the fast lane. Shortly after dropping out of high school to pursue a career in music, Parker married his high school crush, Rebecca Ruffin. Bad news: They weren't going to get a simple "happily ever after." To make this teen romance even more difficult, the pressure to provide was on from the beginning: Records are scarce but it seems that Ruffin was pregnant.

5. He Hit The Road—Literally

With a wife and child to provide for, Parker was eager to start his career. Just months after tying the knot to Ruffin, in the fall of 1936, he hit the road with a traveling band. On his way from Kansas City to the Ozarks, however, he would have an experience that would drastically change his life. And not for the better.

6. He Had Lasting Injuries

On his way to play the opening of Clarence Musser's Tavern near Eldon, Missouri, Parker and his band got into a harrowing car crash. It’s not clear what happened to the other musicians, but Parker sustained terrible injuries, breaking three ribs and fracturing his spine. Those physical injuries, however, would be the least of his troubles.

7. He Was Addicted To…Everything

Parker recovered from his physical injuries in record time. Less than two years later, he was back on the road with pianist Jay McShann, touring the southwest, Chicago, and New York. But he had one lingering—and deep—scar from his accident. As a result of the accident, Parker had become addicted to painkillers—and anything else he could get his hands on.

8. He Was A Dishwasher

After touring with McShann, Parker moved to New York City, where the jazz scene was coming to life. To make ends meet, he worked as a dishwasher at the restaurant where famed pianist Art Tatum played. When he wasn’t washing dishes, however, Parker was quickly making a name for himself on the New York City music scene.

9. He Was About To Have A Breakthrough

Parker could feel that he was on the verge of a musical breakthrough that would change jazz forever. He recalled, “I was jamming in a chili house on Seventh Avenue between 139th and 140th. It was December 1939. Now I'd been getting bored with the stereotyped changes[…]and I kept thinking there's bound to be something else.” He was right—and he was about to find it.

History's most fascinating stories and darkest secrets, delivered to your inbox daily.

10. He Gave Birth To Bebop

Parker might not have known it then but he was about to start a whole new musical genre; bebop. “I could hear it sometimes but I couldn't play it,” he recalled. “Well, that night I was working over 'Cherokee' and, as I did, I found[…]I could play the thing I'd been hearing. I came alive”. And, that night, so did bebop. But not everyone was ready for the change.

11. He Worked All Day And Night

Not everyone was a fan of Parker’s music. In a 1954 interview he confessed, “[...]the neighbors threatened to ask my mother to move once when we were living out West. She said I was driving them crazy with the horn. I used to put in at least 11 to 15 hours a day.” The neighbors let him stay—but Parker’s critics wouldn't always be quite so forgiving.

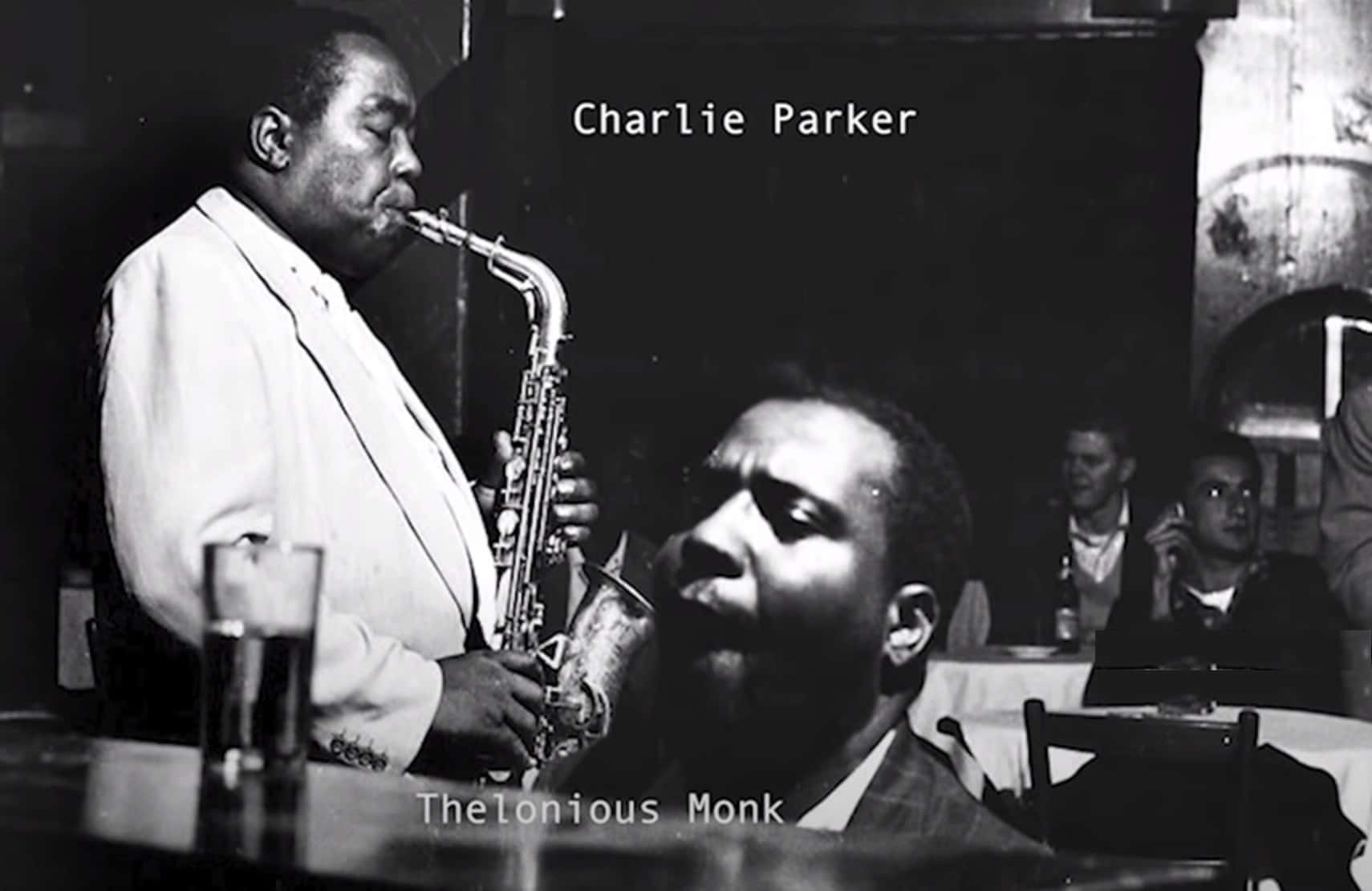

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

12. He Earned His Nickname

Parker’s motivation for practicing as hard as he did might have had more to do with survival (and keeping his head) than anything else. But genius can get a little messy, and Bird's penchant for going off the rails while playing got him into trouble more than once.

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

13. He Got “Gonged Off”

According to legend, a 16-year-old and inexperienced Parker tried to improvise during the song “I Got Rhythm” while playing in Kansas City. This would eventually become Bird's forte, but he was still young, and he completely lost his place. Furious, the band’s drummer Jo Jones “stopped playing, grabbed a cymbal, and threw it on the floor at Parker’s feet." Jones had "gonged" Parker off the stand.

It was humiliating for the fledgling saxophonist—but there’s another, more dramatic, version of the story.

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

14. He Nearly Lost His Head

In 2014’s Whiplash, J.K. Simmons’ recounts a much more lethal version of the story with Jo Jones and the flying cymbal. Allegedly, a frustrated Jones aimed a little higher than Parker’s feet. In this version of the story, Jones launched the cymbal at Parker’s head, nearly decapitating the 16-year-old saxophonist. Talk about playing for your life!

15. He Was A Chicken

Charlie Parker could annoy his bandmates, but they all knew that he could play. Pretty soon, his legend started to grow: The official story is that McShann started calling Parker “Bird” or “Yardbird” because of a curious incident with a chicken on a tour bus. The details of the “chicken incident” are lost to history, but if Parker’s other shenanigans are any indication, it was probably scandalous.

16. He Was Baffling And Extraordinary

Parker’s knack for dramatic improvisation extended far beyond his musical talents. According to The New Yorker, in short order, Parker had “become a baffling and extraordinary [narcotics] addict—one who, unlike most addicts, was also a glutton, [a boozehound], and a man of insatiable [carnal] needs.” And that was being delicate. As we said, genius can be...messy.

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

17. He Had An Insatiable Appetite

In and around the best jazz joints in New York City and Chicago, the name “Yardbird” became synonymous with bebop—and boozy nights. Allegedly, Parker “would eat twenty hamburgers in a row, drink sixteen double [shots] in a couple of hours, and go to bed with two women at once.” Believe it or not, that was just on a Monday.

18. He Went Berserk

It wasn’t long before Parker’s offstage antics turned sinister. In fact, to most of his friends, it looked like Parker was on the verge of another big break—a mental break. “At times, he went berserk,” reported The New Yorker, “and would throw his saxophone out a hotel window or walk into the ocean in a brand-new suit.” But through all the chaos, he still had the music.

19. He Always Needed A Fix

Despite—or, more likely, because of—his addictions, Parker continued making musical magic. As The New Yorker put it, “The only times he could not function were when he was strung out and needed a fix.” But make no mistake; Parker’s lifestyle was catching up with him. And faster than a bebop tempo.

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

20. He Went To The City Of Stars

In December 1945, just as his fame was about to kick into high gear, Charlie Parker’s wild lifestyle finally caught up with him. He traveled to Los Angeles with fellow jazz musicians Dizzy Gillespie, Al Haig, Milt Jackson, and Ray Brown to take bebop to new audiences. But, while the other musicians got ready to perform, Parker was distracted.

21. He Refused To Go On Stage

At the jazz club, Billy Berg’s, in Los Angeles, Parker’s bandmates got started with the first set while Parker stayed backstage. And it wasn’t because he had stage fright. Allegedly, Parker ate “two huge Mexican dinners” and downed enough ale to drown a barman. Suffice to say, the club owner was not impressed with the superstar saxophonist.

22. He Always Made An Entrance

When the club owner tried to get Parker out on stage, he responded by sassing the man off and returning to his drinks. Sometime later—presumably when he finished his bottle—he sent out word to Gillespie to start playing him in. Then, right on cue, he made his way through the crowd to the stage, “playing at full force and at a numbing tempo.”

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

23. He Was Looking For Trouble

Even in his heavily inebriated state, Parker managed to put on a great show. But his Hollywood bender was only just getting started. After the show, when most of his fellow bandmates hopped on the bus back to New York City, Parker hung around, looking for trouble. And he found way more than he could handle.

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

24. He Stayed Behind

Instead of going back home to New York City, Parker stayed on in California. The saxophonist cashed in his bus ticket and used the money to buy smack. As with everything in Parker’s life, it’s not clear what prompted his decision to stay in California. But it is clear what he did while he was there on an extended bender...

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

25. He Set The Town On Fire

Parker’s heavy drinking, substance use and, erm, romantic escapades went into double time in California. Allegedly, on a particularly bad night, Parker ran completely unclothed through the lobby of his Los Angeles hotel room—completely blackout, of course—but not before “setting the bed sheets of his hotel room on fire.” You don't have to be a doctor to realize: Bird couldn't keep this up forever.

26. He Went To The “Loony Bin”

How, exactly, Parker managed to set fire to his Los Angeles hotel room is a mystery. Regardless, the LAPD obviously found the whole incident to be disturbing enough to lock Parker up for the night. And then to commit him to Camarillo State Mental Hospital the next morning.

27. He Was Infantile

Parker spent six months in Camarillo State Mental Hospital as something of a celebrity guest. Even one of the doctors—an avid bebop enthusiast—seemed equally mortified and mystified by Parker. He described the saxophonist as, “A man living from moment to moment. A man living for the pleasure principle[…]his personality arrested at an infantile level.” But they couldn't keep him there forever.

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

28. He Checked Out

Regardless of what the doctors thought of him, Parker managed to check himself out of the mental hospital and back into his musical career. For a while, Parker even maintained his sobriety, but it wasn’t long before he picked up his old beat—and bottle. Only this time, it didn’t look like he was in control (if he ever had been).

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

29. He Was Back In The Habit

Once he was out of the mental hospital, Parker returned to New York City—and fell right back into his old habits. Parker started using hard substances again and it wasn’t long before he was panhandling, collapsing on the streets, getting into “horrendous fights,” and sleeping on the floors and in the bathtubs of his friends’ apartments.

Not exactly behavior befitting one of the most famous jazz musicians in the world—but Charlie Parker clearly never thought about that.

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

30. He Missed The Beat

An incident during a recording session in mid-1946 reveals just how out of control Parker was. Before recording Charlie Parker on Dial Volume 1, Parker downed most of a bottle of usquebaugh. Then, during the chorus of “Max Making Wax” he missed several bars before picking up the rhythm again only to swing around from the microphone.

And that was just the first track.

31. He Couldn’t Stand

While recording “Lover Man,” Parker’s producer had to literally hold him up so that he could play the saxophone. Then, on the final track, “Bebop,” Parker only managed to play eight bars before he started to fade. As in, fade out. Howard McGhee, the trumpeter on the recording, had to shout, “Blow!” to remind him to play.

32. He Was Irresistible

Despite his obvious substance abuse issues, Parker continued playing some of the best jazz music in New York City. And his melodies drove the ladies crazy. The New Yorker described Charlie Parker as an “irresistibly attractive man who bit almost every hand that fed him.” He also managed to break more than a few hearts.

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

33. His Love Life Is A Mystery

The details of Parker’s romantic life are a boozy haze. But what little we do know tells the story of a deeply disturbed jazz musician. Albeit with the libido of a rockstar. Though the details are spotty, it's clear that Parker and his high school flame, Rebecca Ruffin, ended their marriage before 1948. She should have considered herself lucky. Charlie Parker was no Prince Charming...

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

34. He Was A Polygamist

By 1950, Parker was living with his common-law wife, Chan Berg (when he wasn’t strung out on a friend’s sofa). He had two kids with Berg, however, just as with his music, Parker’s love life didn’t follow a simple melody. Even though Parker considered Chan to be his wife, technically speaking, he was still married to yet another woman.

35. He Loved The Mystery Woman

Given the amount of time that Parker spent on blackout benders—or dazzling his doctors at mental hospitals—it’s a wonder that Parker had time to meet any woman. Far less three. Sometime between his first marriage to Ruffin and his second common-law marriage to Berg, Parker had another wife whom we only know as “Doris.”

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

36. He Lost His Instrument

As Parker’s substance use worsened, he managed to collect more wives than saxophones—or “horns” as he liked to call them. By the late 1940s, it seems like Parker never had a horn of his own and had to borrow one just to play at clubs. Fortunately, Parker’s bandmates were always happy to lend a hand. But then, they owed him.

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

37. He Would Have Played For Free

Fellow saxophonist Buddy Tate talked about Parker’s desperation in his final days: “He said he wished people would call him for record dates,” Tate recalled. “I told him they probably didn’t because they’d think he’d want a thousand for a little old forty-two-dollar date, and he said no, he’d do it for free, just to sit in a section again.”

Throughout his life, no matter how much he burned the candle at both ends, Parker always had his music. At the end, he didn't even have that.

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

38. Had No Conscience

At the mental hospital—and throughout his life—it’s not clear if Parker played the tune of hero or villain. He had, after all, left a trail of fiery destruction in his path. But, on the other hand, he brought joy and levity to millions with his music. As one of his doctors put it, Parker only had “the smallest, most atrophied nub of conscience”—but it was there.

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

39. He Could Have Lived A Different Life

Had it not been for his musical talents, Parker likely would have ended up in a very different place. Or, perhaps, the exact same place. His doctor described him as, “One of the army of psychopaths supplying the populations of prisons and mental institutions. Except for his music, a potential member of that population.”

40. He Was A Man Of Many Talents

Robert Reisner, a friend of Parker and author of Bird: The Legend of Charlie Parker, observed, “Charlie Parker, in the brief span of his life, crowded more living into it than any other human being[...]He ate like a horse, drank like a fish, was as [virile] as a rabbit. He was complete in the world, was interested in everything.”

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

41. He Was A Sad Person

In his book, Reisner went on to describe the deep sorrow that ultimately inspired Parker’s musical talents his and tragic, rockstar life: “He composed, painted; he loved machines, cars; he was a loving father[...]No one had such a love of life, and no one tried harder to kill himself.”

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

42. He Paved The Way

Parker’s unique musical style helped forge a path for other jazz legends such as Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis, Bud Powell, Charles Mingus, and Max Roach. But he wasn’t necessarily happy to have all of his bandmates follow in his footsteps. As they all rose to fame, Parker resented Dizzy Gillespie, who received most of the credit for inventing bebop. But that wasn't the only wedge in their relationship.

43. He Resented Gillespie

The public also took to Gillespie in a way that they never did to Parker. As The New Yorker put it, Gillespie was “accessible” and “kind.” However, others described Parker as a “closed, secret, stormy, misshapen figure who continually barricaded himself behind the put-on.” Ironically, Gillespie would be Parker’s last friend.

44. He Had Friends In High Places

In the spring of 1955, Parker was scheduled to play at George Wein’s Storyville in Boston. Before leaving New York City, he decided to stop in at the Stanhope Apartment Hotel to say hello to his friend, the Baroness Pannonica de Koenigswarter. The Baroness was a jazz fan and often showed up to Parker’s shows in a Rolls-Royce.

However, this time, she would need a hearse.

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

45. He Was Parched

Inside the apartment, the Koenigswarter offered Parker a drink, but she was in for a surprise. Much to her consternation and astonishment, Parker turned down the offer of her premium hooch, asking instead for a simple glass of ice water. Parker complained that his ulcer was acting up and that cold water would “quench its fire.” But nothing could quench what was coming.

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

46. He Refused Help

No sooner had Koenigswarter poured Parker a glass of water than he started vomiting up the contents of his stomach—i.e., blood. Koenigswarter immediately sent for the doctor and had him examine Parker. The doctor insisted that he go to the hospital but, unsurprisingly, Parker refused. Sadly, that would turn out to be a big mistake.

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

47. He Was On The Mend

The doctor gave Parker some antibiotics and left him in bed in Koenigswarter’s apartment. After days spent in recovery, Parker appeared to be on the mend. Regaining his strength, Parker moved from the bed to the living room and watched TV. Much like in his songs, however, he was about to strike a dramatic note. And a fatal one.

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

48. He Played His Last Tune

Parker seemed to be in good spirits, watching TV and reminiscing about his youth in Kansas City, Missouri. Then it all came to a sudden end. According to The New Yorker, Parker “started laughing, choked, and slumped in his chair.” Just a minute or two later, the saxophonist was deceased. He had played his final note and drawn his last breath.

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

49. He Looked Much Older Than He Was

The coroner gave Parker’s official cause of expiration as lobar pneumonia. But, in all likelihood, Parker had simply burned out. After examining Parker’s body, the coroner mistakenly estimated Parker’s age to be somewhere between 50 and 60. At the time of his demise, however, Parker was just 34 years old. And flat broke.

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

50. His Friend Paid For His Funeral

Parker’s disastrously complicated love life and marital status led to a nightmare after his untimely passing. His surviving “wives” bickered over his meager estate and funeral arrangements, ultimately leaving it up to Gillespie to settle the affair. Fortunately, Parker and Gillespie had mended fences just a few years earlier.

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

Bird: Not Out Of Nowhere - Charlie Parker

51. He Ended On A High Note

Even after his passing, Parker was full of drama—and unexpectedly high notes. Koenigswarter claimed that, at the very instant of his passing, she heard one, solitary massive clap of thunder. There’s no corroboration of Koenigswarter’s story—it likely wasn’t a stormy night—but getting “gonged off” was in keeping with Parker’s style.