Most people know about Alexander the Great, and of the highly regarded position that he holds in the history of world conquerors and visionaries who influenced history. But he wouldn’t have been able to do any of that without the groundworks that had been laid for decades by his father. And there are two sides to that coin—if it wasn’t for his son, King Philip II of Macedon would have gone down in history as the greatest hero of his nation’s history. These 44 facts only confirm that Philip’s story deserves to be remembered just as much as his son’s.

King Philip II Facts

44. We’ve Stuck Around

Philip was the youngest son of King Amyntas IV, who was the 23rd king of the Argead dynasty. This royal family had ruled Macedon since 700 BC—that’s a full 318 years by the time Philip was born.

43. Dangerous Neighbors

South of Macedon, the Greek city-states were in the grips of a serious hangover after the metaphorical bash of several wars. The Peloponnesian War had lasted nearly 30 years, with Sparta emerging victorious and imposing a tyrannical rule over their fellow Greeks. The Athenians had been ground under their boot, but the city-state of Thebes decided it was their turn to try being in charge. The Battle of Leuctra had resulted in Thebes becoming the preeminent power in Greece.

42. The Wrong Alexander

Amyntas’ eldest son became King Alexander II of Macedon, and he reckoned he could invade the territory between Macedon and Greece known as Thessaly. He occupied their chief city of Larissa, prompting the Thessalians to ask the city of Thebes for help against the Macedonians. They sent their most skilled general, Pelopidas, to drive the Macedonians out. Alexander brokered a deal which meant he had to send several noble hostages to Thebes as a guarantee of his good behavior.

41. He Bunked up with Theon Greyjoy

At the age of 14, Philip was sent south to Thebes as a hostage, living with the Theban general Pammenes for three years. He left Macedon in the hands of a regent who ruled on behalf of Philip’s surviving older brother, Perdiccas.

40. Awkward Living Conditions

We’re just going to say it: the young Prince Philip was in a relationship with Pammenes while he lived in Thebes. As some people might know, relationships in Ancient Greece were viewed much differently than they are today. Admittedly, we don’t fully know how far Pammenes went in his relationship with the teenage Philip but given that sources wrote of Pammenes’ dealing in pederasty, we are forced to consider the possibility of what their relationship may have been.

39. Foreign Exchange Student

Philip’s captivity in Thebes led to an education which would change his life for the better. Because he was a royal hostage living with the high-ranking general Pammenes, Philip also got to learn military tactics from Pelopidas and Epaminondas. These men had shaped the Theban military to defeat the Spartans and Athenians in battle, so it was worth paying attention when they had something to say about warfare.

38. Back at the Ranch…

Philip’s brother, Perdiccas, reached adulthood and took charge of the kingdom of Macedon. Because this was ancient Macedon, he had to do it by killing the regent who was ruling in his name—presumably while shouting “There can be only one!” By the time Philip returned to Macedon, Perdiccas had secured his place as king, and he had a newborn son named after their father, Amyntas.

37. Disaster

Macedon’s northern border was threatened by their Illyrian neighbors, who had united with the Dardanians under their king, Bardylus. King Perdiccas rode out to confront these barbarian tribes, but the ensuing battle didn’t go well for him. He and 4,000 of his soldiers died in battle, even as Bardylus occupied the northern Macedonian lands.

36. Brother From Another Mother

A famous story alleges that Philip fathered an illegitimate son with a noblewoman named Arsinoe, whom he later gave in marriage to a man named Lagus. The boy in question was named Ptolemy, and many of you will know that he would not only be a close friend of Philip’s heir, Alexander, throughout his life, but he would later create a dynasty as Pharaoh of Egypt after Alexander’s death. Ptolemy would also bury Alexander in Alexandria. Many say that Ptolemy himself made up the story about Philip being his dad, though, with seven wives, it wouldn’t be outside of Philip’s character. And it does add a fascinating twist on Ptolemy’s role in Alexander’s life and death.

Sign up to our newsletter.

History’s most fascinating stories and darkest secrets, delivered to your inbox daily. Making distraction rewarding since 2017.

35. Tough it Out

New weapons weren’t the only things Philip introduced. Recognizing the need for toughness in his army, Philip banned wheeled transport for the officers, so that they marched alongside the men. He set a cap of camp servants at one for every 10 infantrymen and one per cavalryman. He also limited their bathroom breaks and enforced healthy snacks only while on the march—no wait, that’s a kindergarten teacher. Nevermind.

34. Macedon’s Darkest Hour

In the aftermath of King Perdiccas’ death, however, one would be forgiven if they thought Macedon was done for. Bardylis and his Illyrians had taken much northern territory, the Paionian tribes to the west began raiding Macedon at the same time as Bardylus. To make matters worse, a pretender to the throne named Argaeus landed in the south of Macedon with an army of mercenaries backed by Athenian gold to take the Macedonian throne, which was occupied by an infant boy.

33. The Hero we Deserve, and the One We Need

Philip was given the position of regent to his nephew, but instead, he saw his chance to take the throne for himself. He usurped the throne and became king. Most would have cynically assumed that he was only going to be King for a short while, but this was just the first of many surprises that Philip would provide the world.

32. Let’s Have a Little Chat

Philip proved that he had a gift far more valuable than his own prowess in arms, or even his knowledge of military skills. He was incredible at diplomacy. He barely put the crown on his head before he had negotiated with the Athenians to withdraw their support for Argaeus—who would later die in battle with Philip—and he also bought off the Paionians with bribes to leave Macedon alone.

31. An Offer He Couldn’t Refuse

Philip’s master-stroke, however, happened when he rode to negotiate with Bardylus on the fate of Macedon. Somehow, Philip made a deal with the Illyrians to be satisfied with the land they had taken rather than keep going for the rest of Macedon. This deal was sealed with Philip taking Bardylus’ great-granddaughter, Audata, to be his wife—though some sources claim it was Bardylus’ daughter, though that would have made Bardylus a very old father at age 89. Either way, Philip bought Macedon a year of peace, and Philip had every intention of using every second of it to save Macedon.

30. Paging Dr. Freud

Audata, like most Illyrian women, was trained in the art of riding and warfare. She would pass on these skills to her daughter Cynane, who was her only child with Philip. Interestingly, sources indicate that Audata changed her name to Eurydice when she married Philip, which had been the name of Philip’s mother, who had also been of Illyrian descent.

29. So Much for Family Reunions

In 358 BC, just a year after making peace, Philip marched an army of Macedonian soldiers against his new Illyrian in-laws. Bardylus and Philip’s forces were almost evenly matched, but the Macedonians had been rigorously trained in the newer methods of battle which the Illyrians would not have been expecting. Regardless, the battle was fierce, and the 90-year-old Bardylus allegedly led his troops while on horseback, dying in the thick of the fighting. By the end, Philip was victorious, and the Illyrians were forced to pay Macedon tribute.

youtube

youtube

28. On a Roll

After his first taste of victory, Philip went on a rampage. When the Paionian king died, Philip took advantage of the power vacuum by conquering Paionia and adding it to Macedon’s territory. He also spat in the faces of the Athenians by seizing the coastal town Amphipolis, which was a highly valuable port to Athens. Give him an inch, he takes a whole port town.

27. You Just Made Yourself a Powerful Enemy!

Athens was furious at the turnaround behavior of Philip, but one man was especially ticked off at this blatant power grab. Demosthenes would never forget the actions of Philip, and he cemented his name in history with a series of rousing speeches to rally the Athenians against Philip’s ambitions. The speeches, known as the Philippics, were made at various points in Demosthenes’ career as a politician and orator, and fueled Athenian resistance to the Macedonian expansion.

26. One Isn’t Enough

Philip may have been a bit cynical about marrying for love. After marrying Audata—who stayed married to him even after he had subjugated her people—Philip took two more wives in rapid succession. One was named Phila of Elimeia, the other was Nicesipolis of Thessaly—try saying that six times quickly!

25. Four’s a Crowd? Nonsense!

Epirus was a king found northwest of Greece that was ruled by King Arymbas. Philip wanted to make Arymbas an ally, so he sweetened the deal of an alliance by taking Arymbas’ niece as his fourth wife. Her name was Olympias, and she became the leading wife of his ever-growing harem.

24. A Son to Surpass his Father

A year after marrying Olympias, Philip allegedly received several pieces of good news in rapid succession. His horse had won its races during the Olympic games that year, and one of his top generals, Parmenion, won a great victory against the tribes north-east of Macedon. On top of that, Olympias bore him his first son, Alexander.

23. Dictator or Diplomat?

While all this was going on, though, Philip became embroiled in politics in Thessaly. In the years since Alexander II’s death, Thessaly had fallen victim to tyrants of Pherae, as well as infighting amongst themselves. Sources indicate that Philip married his second and third wives to broker a peace agreement amongst the Thessalians, which built up his own influence in that area.

22. Macedonian Crusade?

All that negotiation didn’t deter the people of Phocis from stirring up trouble in the worst way possible. They captured and looted the sacred Oracle of Delphi, which contained many undisturbed treasures that paid for a lot of mercenaries. For the rest of Greece and Thessaly, however, this caused them to declare a Sacred War—the third of its kind by that point in history. Philip got himself involved, and while the road wasn’t easy, and he was driven out of Thessaly, he returned to crush his enemies at the Battle of the Crocus Field, leading to him being recognized as the leader of the Thessalians, gaining him a new army and more resources.

21. It Cost Me an Eye

In 355, Philip laid siege to Methone, which was a city on the Macedonian Gulf controlled by Athens. It was during this siege that an archer from the city shot Philip in the face with an arrow. The damage was so severe that Philip’s eye had to be surgically removed. Despite this setback and the arrival of Athenian reinforcements, Philip took the city in 354, presumably killing any man who called him “Cyclops”.

20. Let’s Repeat History!

At one point during Philip’s military campaigns in the north of Greece against the Phocians, he considered marching into Central Greece. However, Demosthenes delivered one of his most fiery Philippics, and the Athenians occupied the pass known as Thermopylae to block Philip just like the Spartans had done to the Persians. Philip, however, was too smart to try his luck against them—and he didn’t want to be known as a tyrant to the Greeks, at least in reputation—so he stayed out of Central Greece. For a little while, at least.

19. We Need Some Variety

One reason for Philip’s military success was that his battle strategies didn’t exclude adding different kinds of units to the Foot Companions and the Companion Cavalry’s modus operandi. So, the more regions he conquered, the more diversity entered his army, whether it was the heavy cavalry from Thessaly, the Paionian light cavalry, Greek hoplites, or the Thracian cavalry which served as scouts. Philip also hired skilled archers from Crete and slingers from Rhodes to add some range to his weaponry—pun intended. Alexander would go further, adding even more units to his army while campaigning in the east.

18. Oh the Ego

Philip had a penchant for naming things after himself. In 356 BC, Philip captured gold mines around the city of Crenides, which allowed him to fully support a standing army in Macedon. To celebrate, he renamed Crenides ‘Philippi.’ When he campaigned against the Scythians in 342 BC and conquered the settlement of Eumolpia, he renamed it Philippopolis. This trait passed down to his son, who named upwards of 18 settlements Alexandria.

17. Shots Fired!

In the latter half of his reign, things were getting complicated at home, when Philip married his seventh, and final wife, a young woman named Eurydice. This caused trouble for Olympias and Alexander, because Eurydice was a full Macedonian, which meant any children she would bear could threaten to take Alexander’s place as heir. At the wedding reception, her uncle Attalus drunkenly joked about having a legitimate heir to the throne, and the teenaged Alexander took umbrage at being called a bastard. When Philip broke up the brawl by demanding his son apologize to Attalus, Alexander argued with him so furiously that Philip stood up to run him through with a sword. Thankfully, he was so drunk that he stumbled and fell after a few steps. Alexander famously mocked his father for making “preparations to pass out of Europe into Asia, overturned in passing from one seat to another.” After everyone in attendance presumably shouted “OH SNAP!” Philip had Alexander and Olympias banished.

16. Not Again!

While Olympias went back to her home in Epirus, Alexander took refuge with the Illyrians, and despite—or maybe because of—the fact that the young prince had defeated them in battle, they treated him with honor. After six months, though, Philip and Alexander were reconciled, although things were still contentious between them. When a governor within the Persian Empire offered his eldest daughter in marriage to Alexander’s half-brother, Philip Arrhidaeus, Alexander got paranoid that his inheritance was at risk again. He went behind his father’s back and pointed out to the governor through a messenger that Philip Arrhidaeus was what modern society would call intellectually deficient—this wasn’t slander on Alexander’s part, just a fact that the governor didn’t know about—and offered himself as a more suitable husband for the governor’s daughter. When Philip found out about Alexander’s dealings, he was livid, as the whole thing had just been an attempt at getting an alliance within the Persian Empire for the cheap price of getting his disabled son a wife. The negotiations were called off, and Alexander presumably sulked until the next military campaign.

15. Take Your Son to Work Day

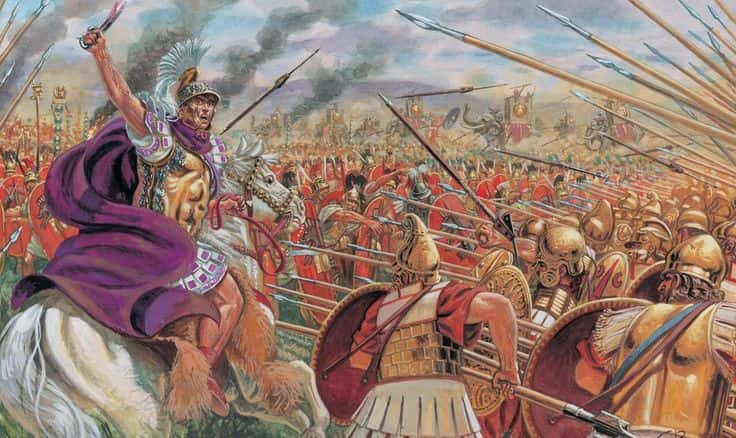

By 338, Philip had made Macedon the most powerful kingdom in the Balkans, but he wasn’t quite done yet. The Greek city-states still resisted him, so he led an army of 30,000 infantry and 2,000 horsemen south that year to settle things once and for all. The big battle happened at Chaeronea, where 35,000 Greek allies had gathered, particularly the forces of Thebes and Athens. With the help of the then-18-year-old Alexander, Philip and his forces won a bloody victory, leading to Philip forging the League of Corinth, which allied most of the Greek city-states with Macedon.

pinterest

pinterest

14. An Old Enemy

Surprisingly, one of the men fighting Philip among the Greeks was none other than Demosthenes! He had taken up armor and weapons, so he could personally take part in driving Philip out of Greece. In the aftermath of Chaeronea, Philip’s hatred for Demosthenes caused him to mock and taunt him, along with the other defeated Athenians, before he was admonished for being a sore winner. Bizarrely, Demosthenes would outlive not only Philip, but Alexander too.

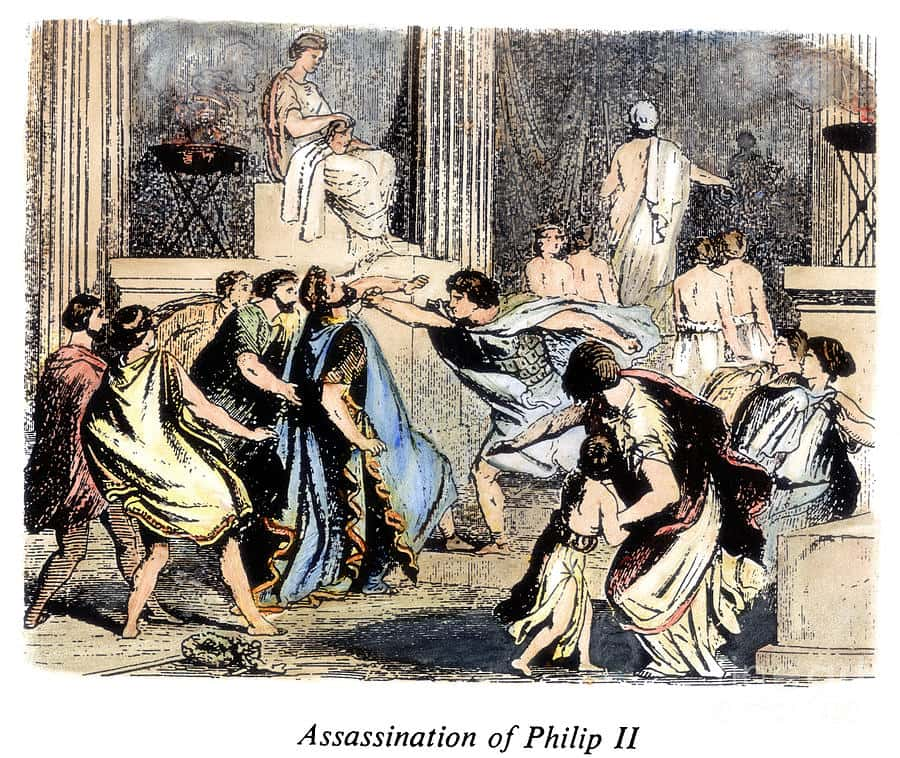

13. An Abrupt End

Two years after the Battle of Chaeronea had made Philip master of Greece, he hosted a grand wedding at Aegae between his daughter, Cleopatra (no, not that Cleopatra), and King Alexander (no, not that Alexander) of Epirus. Philip was determined to walk into the public area alone and unguarded to prove to the Greek guests that he was no tyrant who needed to fear his subjects. Ironically, it was one of his royal bodyguards, a man named Pausanias, who then confronted him and stabbed him to death before fleeing.

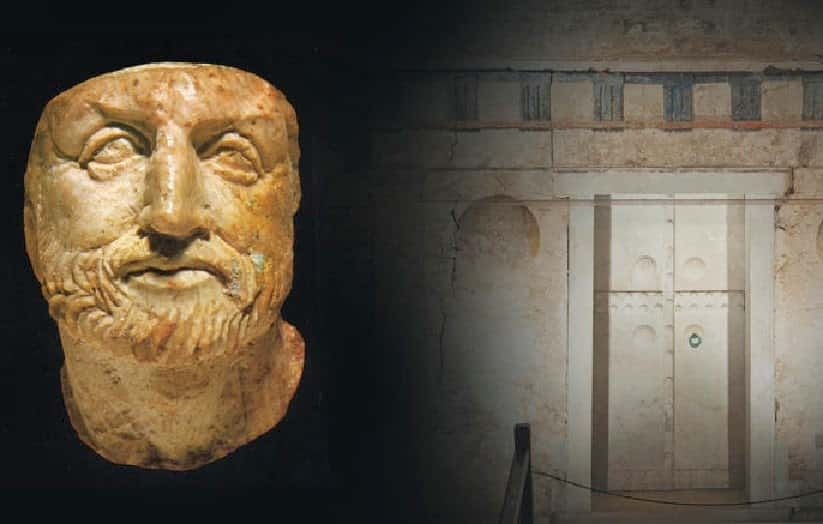

12. Hey! I'm Buried Here!

In 1977, Philip’s tomb was uncovered at Aigai by Greek archaeologists. The tomb was one of two which had been completely undisturbed over the centuries. Philip’s remains were identified by the damage to one of the body’s legs, as well as damage to the right eye.

11. What a Coincidence

Pammenes and Epaminondas, the men most associated with Philip’s captivity in Thebes, were both involved with the elite unit called the Sacred Band of Thebes. This fighting regiment consisted of 150 male couples. The idea was that men would fight hardest if they fought side-by-side their lovers. This proved an effective strategy given how highly regarded the Sacred Band was. They were responsible for many Theban victories until they were annihilated by a fully-grown Philip and his army at the Battle of Chaeronea. No hard feelings, we guess?

10. Strange Dedication

Out of seven wives that Philip took in his life, his second-to-last had been a Thracian named Meda of Odessos. Allegedly, when Philip was assassinated, Meda took her own life so she could join Philip in death. This kind of behavior was uncommon in Macedonian culture, but her wish was held up, and she is believed to be buried with Philip in his tomb.

9. Great Father’s Day Gift

While Alexander distanced himself from his father after Philip’s death, he never forgot his father, or all that he had helped make possible. Alexander’s final will allegedly had demanded for, among other things, the construction of a huge tomb for his father, King Philip. Alexander gave instructions that it must “match the greatest of the pyramids of Egypt.” Sadly, the world was too busy being torn apart to build this incredible monument to Philip.

8. Revenge is Best Served on Fire

While Philip lived to see the Greeks, including the Thebans, utterly submit to his authority, he spared Thebes from a destructive vengeance that many must have assumed he was itching to unleash for those years in captivity. However, he left that business to his son, Alexander. While Alex was consolidating his kingship, a rumor spread that he had been killed in battle, leading Thebes to rebel. When they refused to back down when faced with Alexander approaching, it was the final nail in their coffin. Alexander not only razed the city to the ground, he either killed or enslaved the entire population of Thebes.

7. Big Plans

By the time of his death, Philip was planning a large-scale invasion of Persia, just across the water. He intended to go as an avenger of past humiliations and insults launched against the Greeks. In fact, several of his top generals were leading an advance army into Persia when he was killed, adding to the chaos of the moment. Alexander would go on to lead the Macedonians and Greeks east instead, leading to him securing his own place in history.

6. Sons of a God

Philip and the other men of the Argead dynasty boasted that they were descended from no less a figure than Heracles himself—that’s Hercules for the Disney fans reading this. That would have made them divine men, since Heracles had been a demi-god. Philip’s son, Alexander, however, preferred to associate himself with his mother’s supposed ancestor, Achilles.

youtube

youtube

5. No Tower for This Prince

So, what happened to the rightful king, you might be asking. What horrible thing did Philip do to his nephew Amyntas, the rightful king whose throne Philip usurped? Surprisingly, Philip decided that Amyntas was no threat to him and gave him a comfortable position in his court. Philip even gave his daughter, Cynane, in marriage to Amyntas. It wasn’t until Philip’s death that things got dangerous for Amyntas. He was executed by Alexander, who was dealing with potential rivals to the throne. Should’ve laid low, Amyntas!

4. Go Tell the Spartans

During his years of campaigning, Philip famously sent a threatening message to the city of Sparta. He declared that if he entered their land, he would raze Sparta to the ground and enslave the Spartans forever. The Spartans sent back just one word as a reply: “If.” Philip backed down, and his mastery over the Greeks exempted Sparta as the only place that withstood him.

3. Bizarre Love Triangle

The reason for Pausanias’ murder of Philip has been contested for centuries. The most common story was always that Pausanias and Philip had had a sexual relationship, but Philip moved on to a younger man. Pausanias jealously tormented Philip’s younger lover, which angered Attalus, a high-ranking general and nobleman who was also a friend of the younger man. Attalus and his associates allegedly sexually assaulted Pausanias, and when Philip found out about it, he preferred to bribe Pausanias with a promotion to the royal guard rather than pursue vengeance. Pausanias never forgot this slight, and eventually took his revenge. Many have questioned this story, though a better idea—or more dramatic option—has yet to be found.

2. Just Behaving Like Any Widow

Because of Philip and Olympias’ stormy relationship, there has been a lot of speculation that she was behind Philip’s murder in one way or another. One story told by the Roman historian known as Justin insists that after Pausanias was killed while trying to flee, his body was put on display and on the first day of Olympias’ return to Macedon, she put a crown on Pausanias’ head and publicly honored him. Many doubt the authenticity of this story, as any such behavior would have been badly received by a population that had grown to love Philip. For his part, Aristotle dismissed any idea of Olympias or Alexander being involved in Philip’s murder.

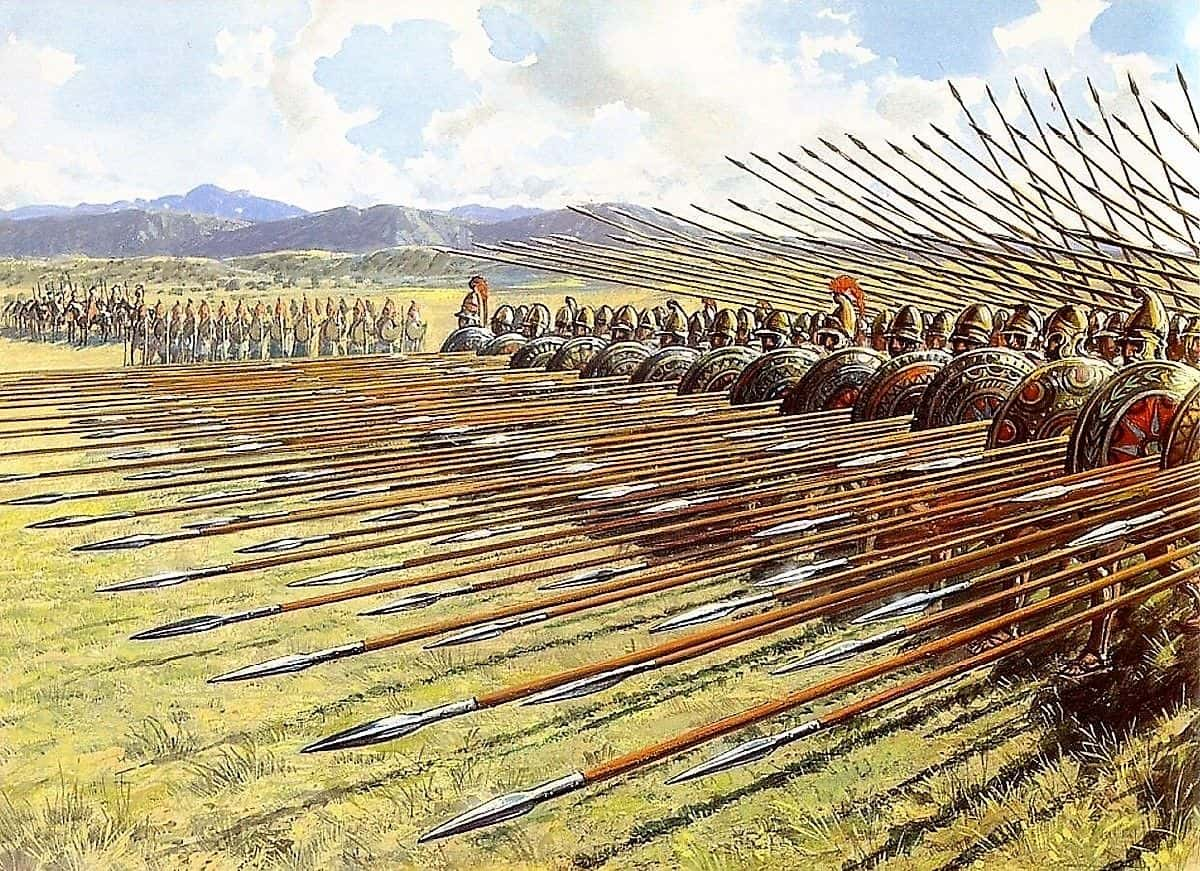

1. Let's Get Down to Business!

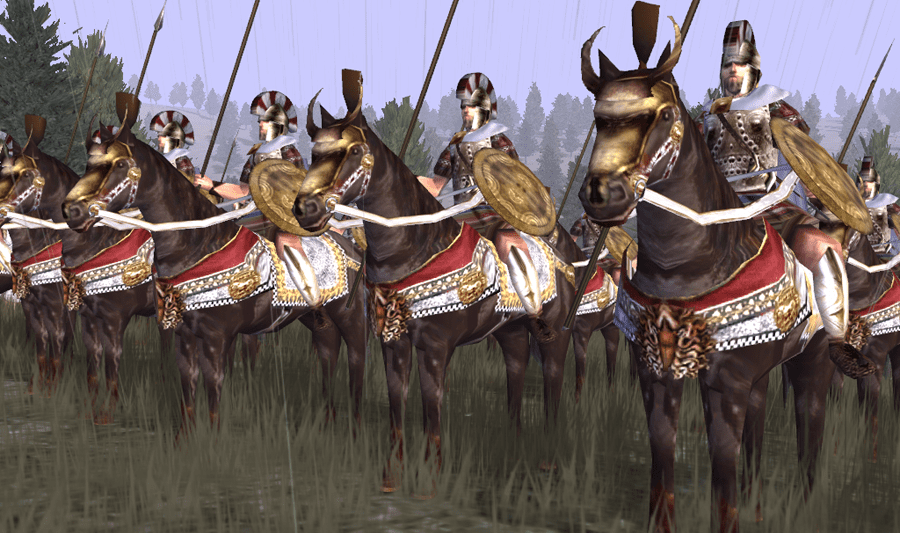

After he returned to Macedon, Philip had begun implementing a series of military reforms to the Macedonian army which he’d picked up while being a hostage in Thebes. One of the most important tactics he implemented was equipping the infantry with eighteen-feet long spears known as sarissas. The infantry were taught to fight in the phalanx, keeping rows of spears in front of the men when attacking their enemies. He also took the elite cavalry of Macedon (known as the Companion Cavalry) and replaced their traditional javelins with lances and turned them into the first shock cavalry unit in antiquity.

Sources: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18