1. Pros and Cons

When we think of schemes and scams we think of ‘con artists.’ ‘Con,’ in this case, is an abbreviation of ‘confidence,’ as in ‘confidence man’ or ‘confidence trick.’ These terms gained popularity through the satirical writing of Dr. James Houston, who sarcastically described an unsophisticated swindler, Samuel Thompson, in this manner. However, Houston’s readers misunderstood his writing, and Thompson gained a reputation as a master criminal!

2. Name Rings a Bell

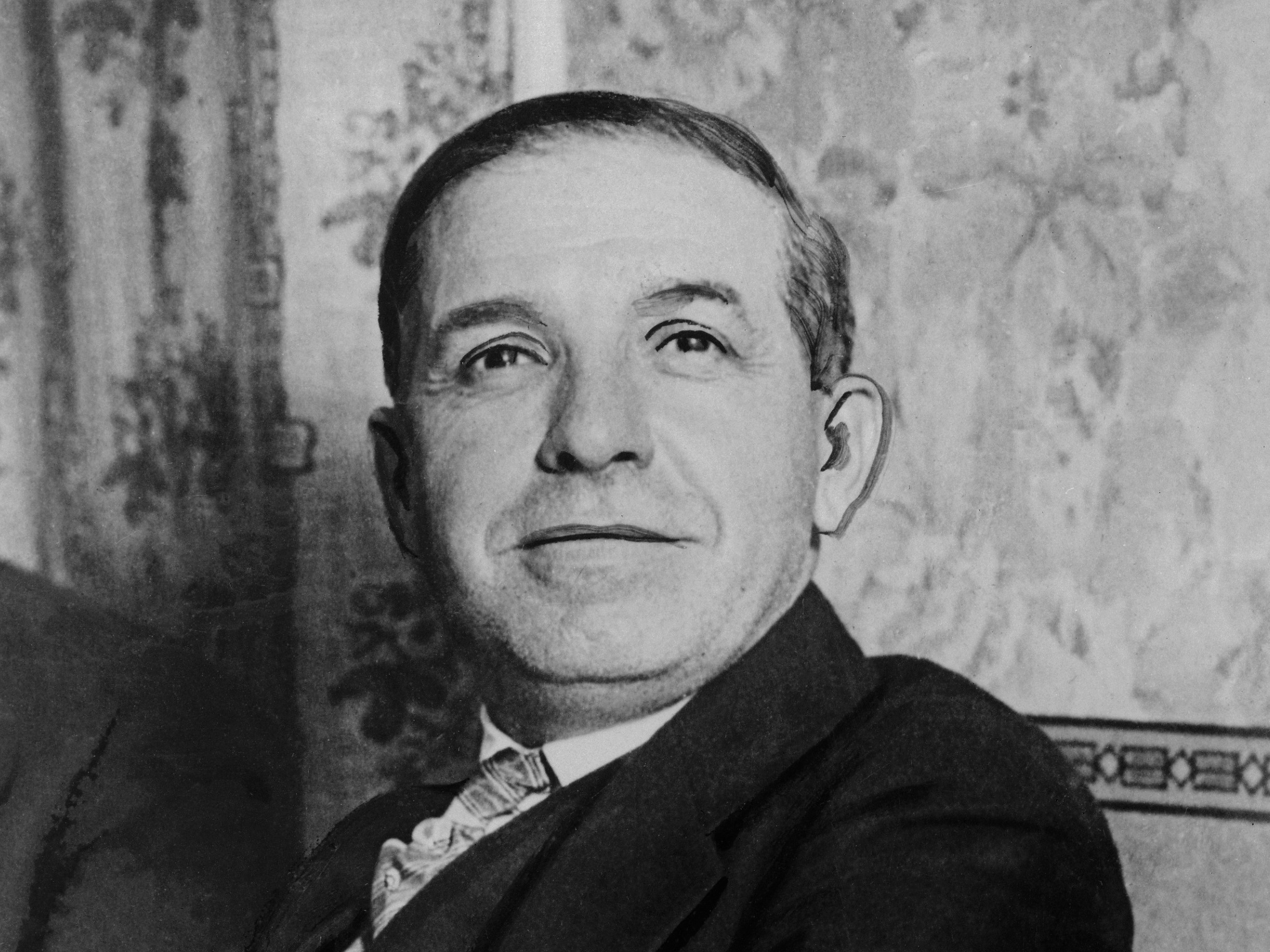

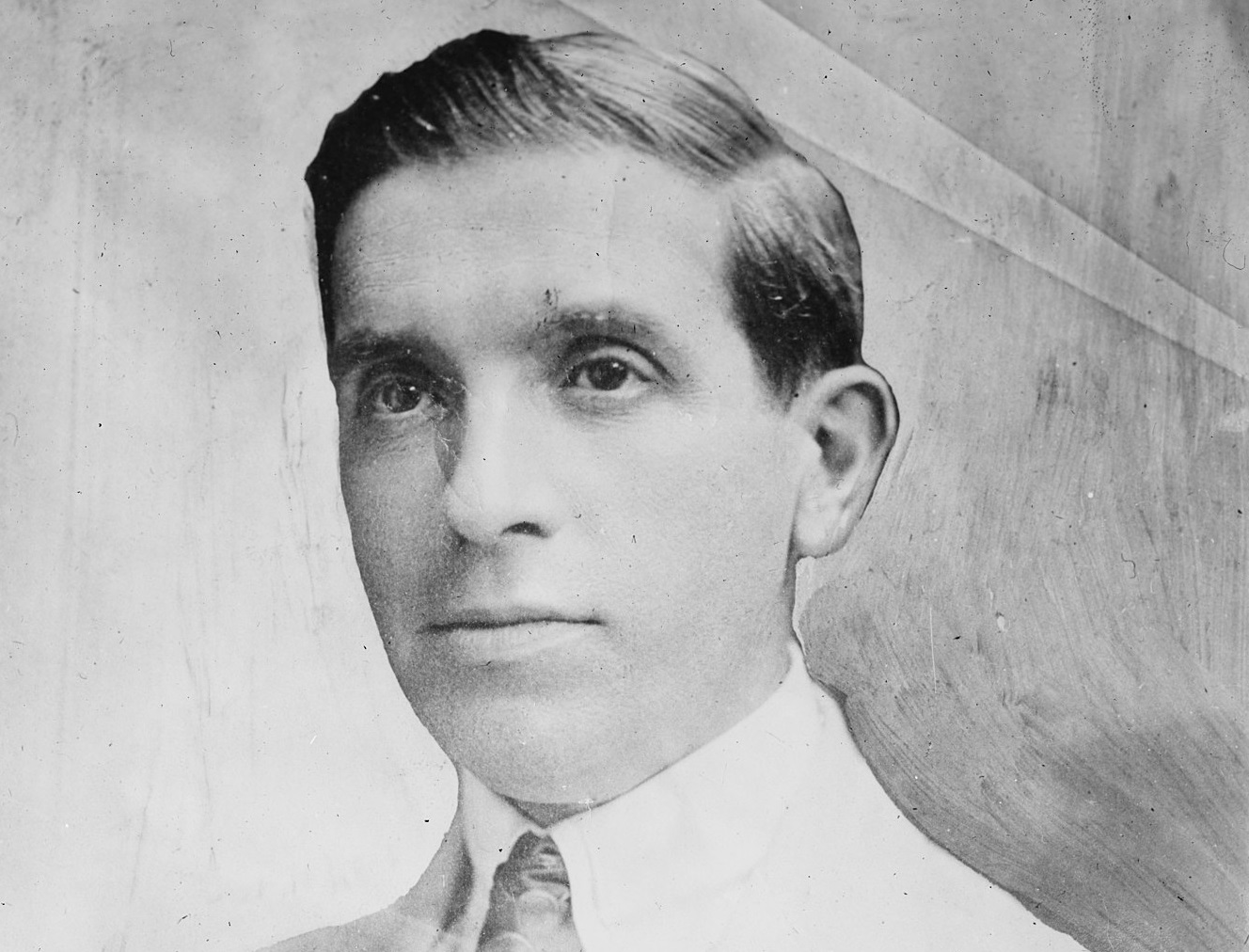

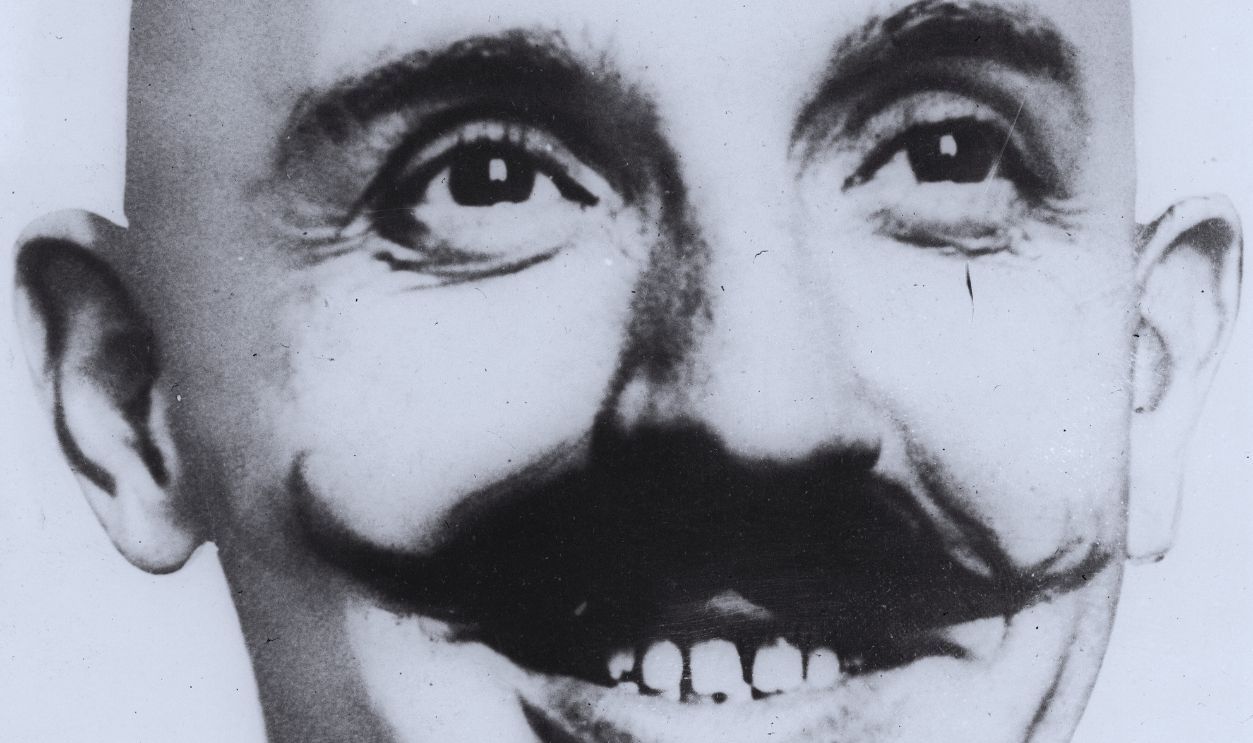

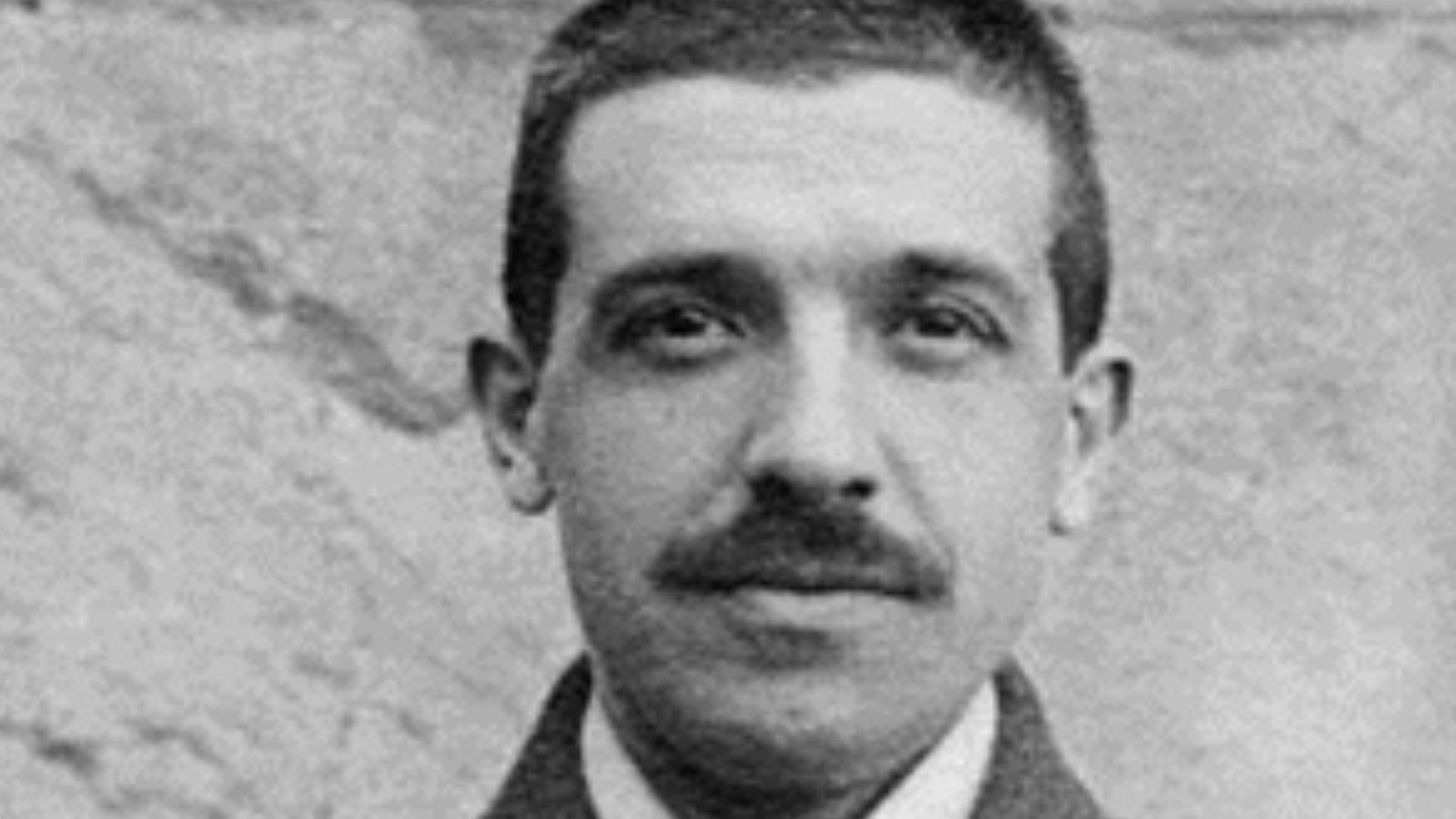

While Samuel Thompson may have been the first con man described as such, Carlo Pietro Giovanni Guglielmo Tebaldo Ponzi, born 33 years after the term was coined, in 1882, is perhaps the most famous.

3. Humble (Criminal) Beginnings

Ponzi grew up in Italy but arrived in Boston on November 15, 1903. He quickly learned English, gained employment in a restaurant, and worked his way up to waiter, where he got fired for short-changing customers. Once a scammer, always a scammer.

The original uploader was Mgreason at English Wikipedia., Wikimedia Commons

The original uploader was Mgreason at English Wikipedia., Wikimedia Commons

4. La Metropole

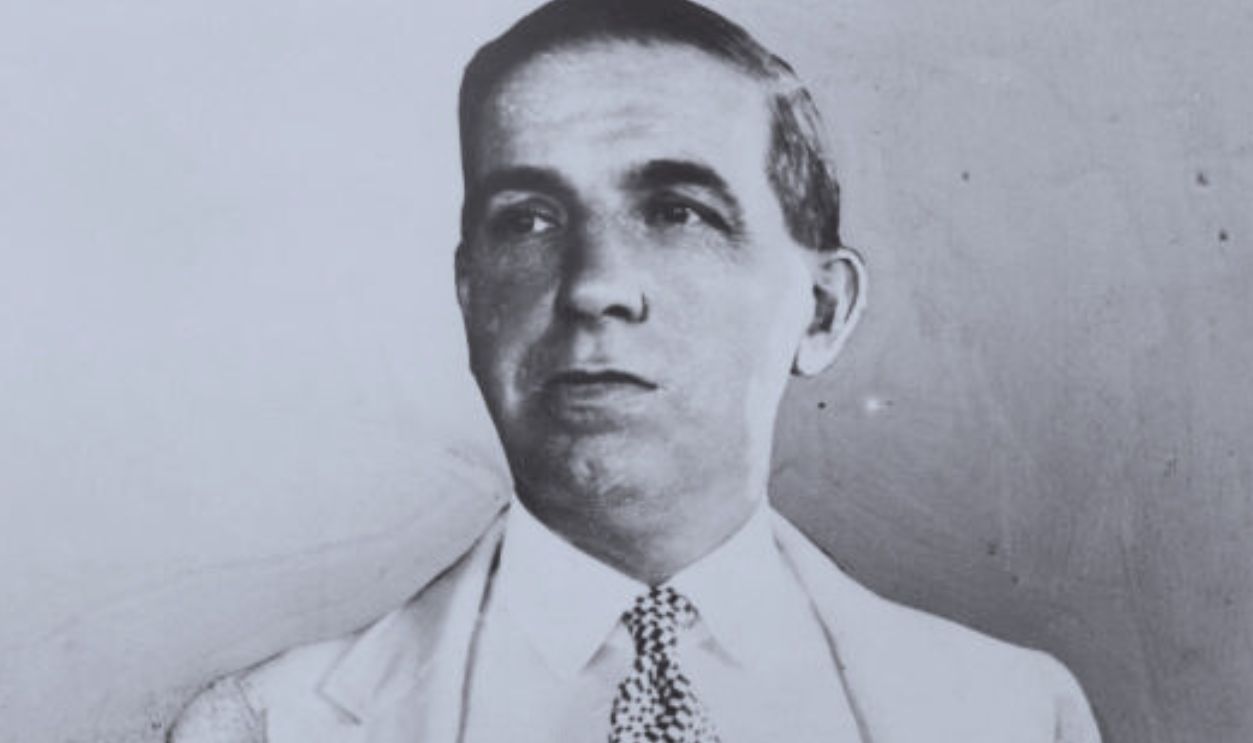

After failing to make much money in the US, Ponzi moved to Montreal in 1907. Having learned French, and already speaking Italian and English, he was able to get a job at the newly opened Banco Zarossi—a bank primarily serving Italian immigrants in Montreal. However, the owner was using the money from newly opened accounts to pay off debts and was eventually run out of town.

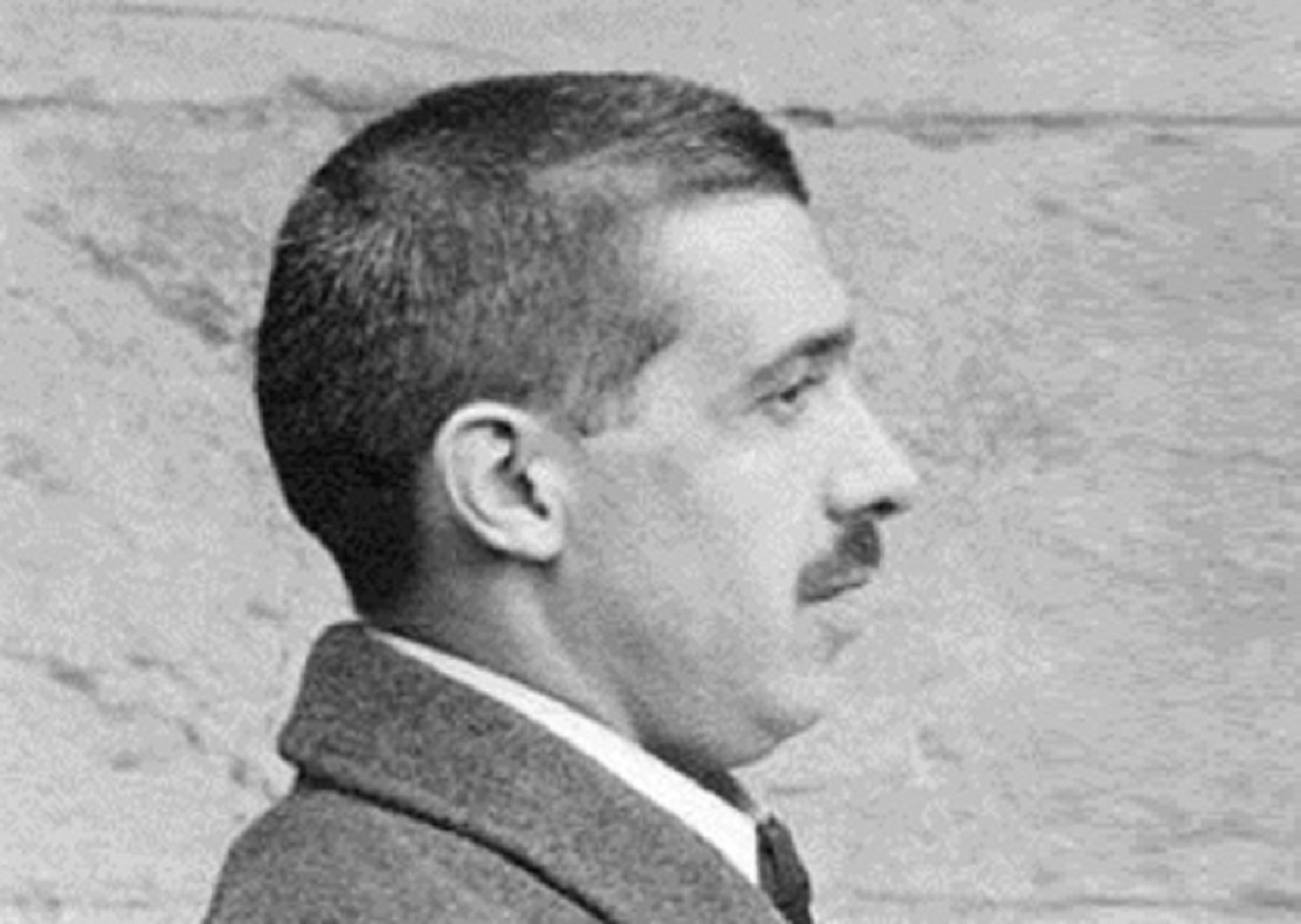

Boston Library (NYT); en.wikipedia.org, Wikimedia Commons

Boston Library (NYT); en.wikipedia.org, Wikimedia Commons

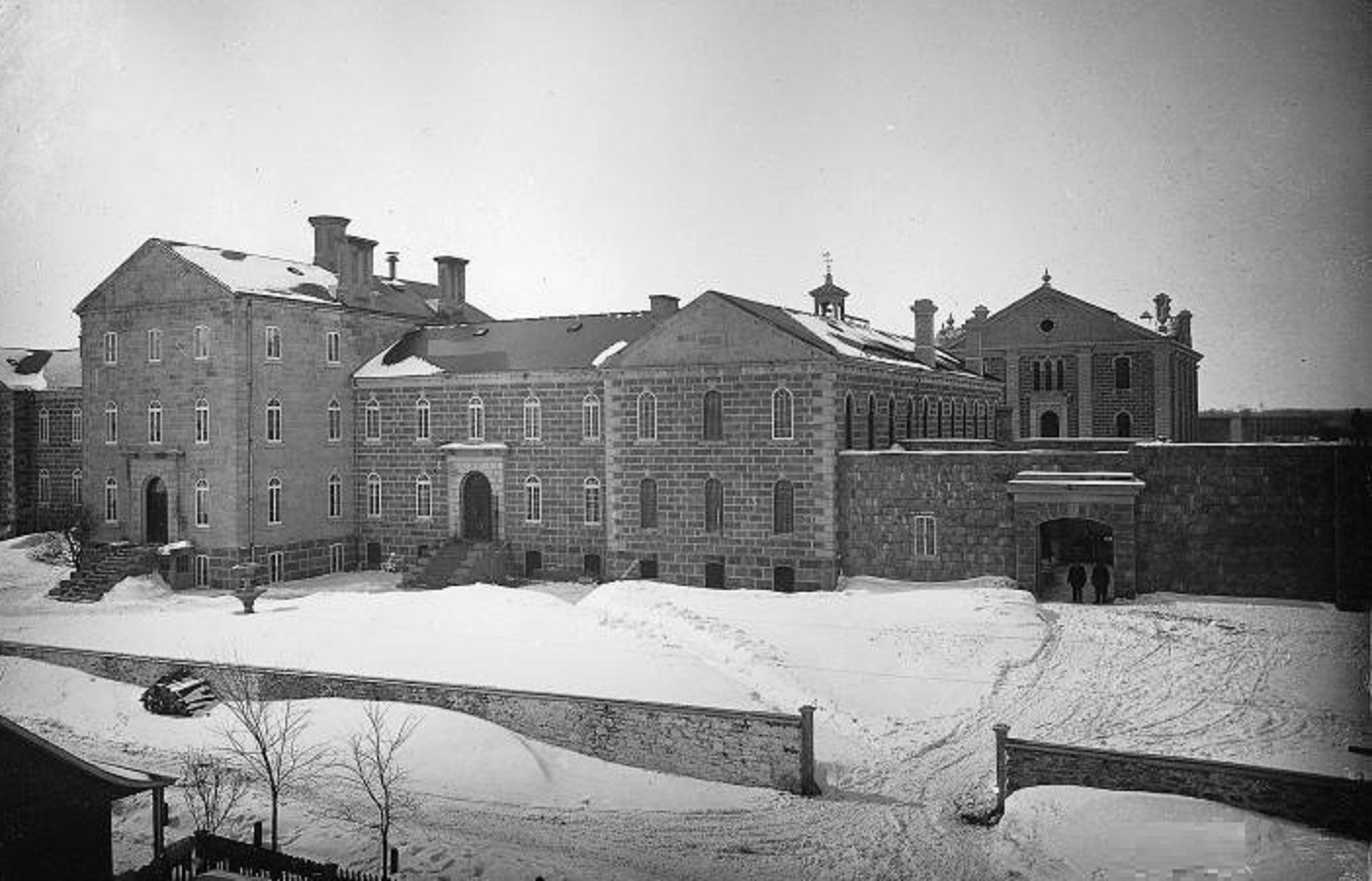

5. Famiglia Abbandonata e Mea Culpa

After his ex-boss fled to Mexico, Ponzi moved in with Zarossi’s abandoned family. He tried to help them out, but a lack of funds and his own desire to return to the US led to him forging a check he found in the empty office of a previous Zarossi client. He subsequently served three years at Saint-Vincent-de-Paul Penitentiary.

6. Back on the Chain Gang

On his way back to the US, Ponzi got caught in an immigrant-smuggling scheme and ended up serving two years in an Atlanta prison. And to think, he could've stopped there and Ponzi scheme would've meant an entirely different thing.

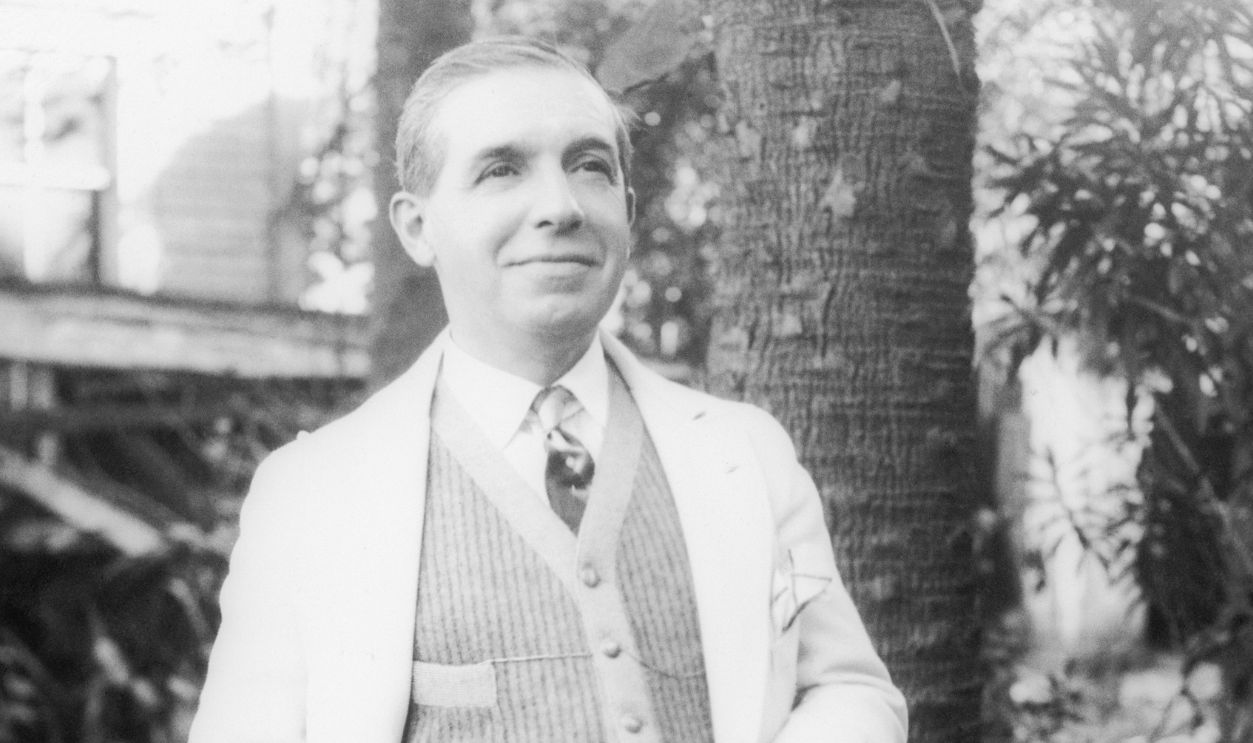

US Goverment, Wikimedia Commons

US Goverment, Wikimedia Commons

7. Gimme Some Skin

After being released from jail for the second time Ponzi got a job as a nurse in a mining camp. When a fellow nursed suffered severe burns Ponzi volunteered to donate 220 square inches of his own skin. The subsequent operations resulted in pleurisy for Ponzi. That's a pretty big sacrifice for a man who mostly took from others.

8. Post-Marriage Plans

Ponzi met his wife Rose Maria Gnecco upon his return to Boston, and the two were married in 1918. After taking over, but being unable to revive his wife’s fruit business, Ponzi decided to work for himself. He came up with various ideas and wrote to European acquaintances to try to sell them on his plans. One interested correspondent from Spain sent an IRC (International Reply Coupon) with their inquiry. Ponzi figured that the IRC (which was bought for the cost of postage in its home country, but exchangeable for the cost of postage in the new country) could potentially be used to profit from differences in postal costs. The cost of postage had greatly decreased in Italy after the First World War, and Ponzi figured that exchanging an Italian IRC for American postage could net him an estimated 400% profit.

9. A Scheme is Born

Unfortunately, Ponzi did not have the start-up capital necessary to buy the initial order of European IRCs. So he started a stock company that promised investors huge amounts of interest on their money. By January 1920, Ponzi started his Securities Exchange Company. (It’s not a coincidence that the US Securities and Exchange Commission, established in 1934 to regulate the industry and protect investors, has a very similar ring to it.)

Pictorial Parade, Getty Images

Pictorial Parade, Getty Images

History's most fascinating stories and darkest secrets, delivered to your inbox daily.

10. (Multi-) Million Dollar Pyramid

In January 1920, the first month of Ponzi’s SEC, 18 people invested $1,800. In February he paid back his original investors with money from new investors. As word spread of this great financial opportunity, things escalated quickly. Like, really quickly. By May 1920, Ponzi had made $420,000, or about $5 million, adjusted for inflation. By June people had invested $2.5 million ($30 million with inflation). By the end of July Ponzi was taking in about $1 million ($12 million with inflation) a day.

11. A Whole Lot of Postage

Throughout all of this “investment,” Ponzi was largely able to pay previous investors with the money coming in from new investors. However, recall that the original plan for Ponzi’s business was exchanging lesser value postage for higher value postage. While he was able to do this, Ponzi had not yet figured out how to exchange the postage for cash. He also, to his credit (?), realized the logistical impossibility of purchasing, transporting, and exchanging the ludicrous amounts of IRCs that would be necessary to pay out the millions in investments he had accepted.

12. Bad Press

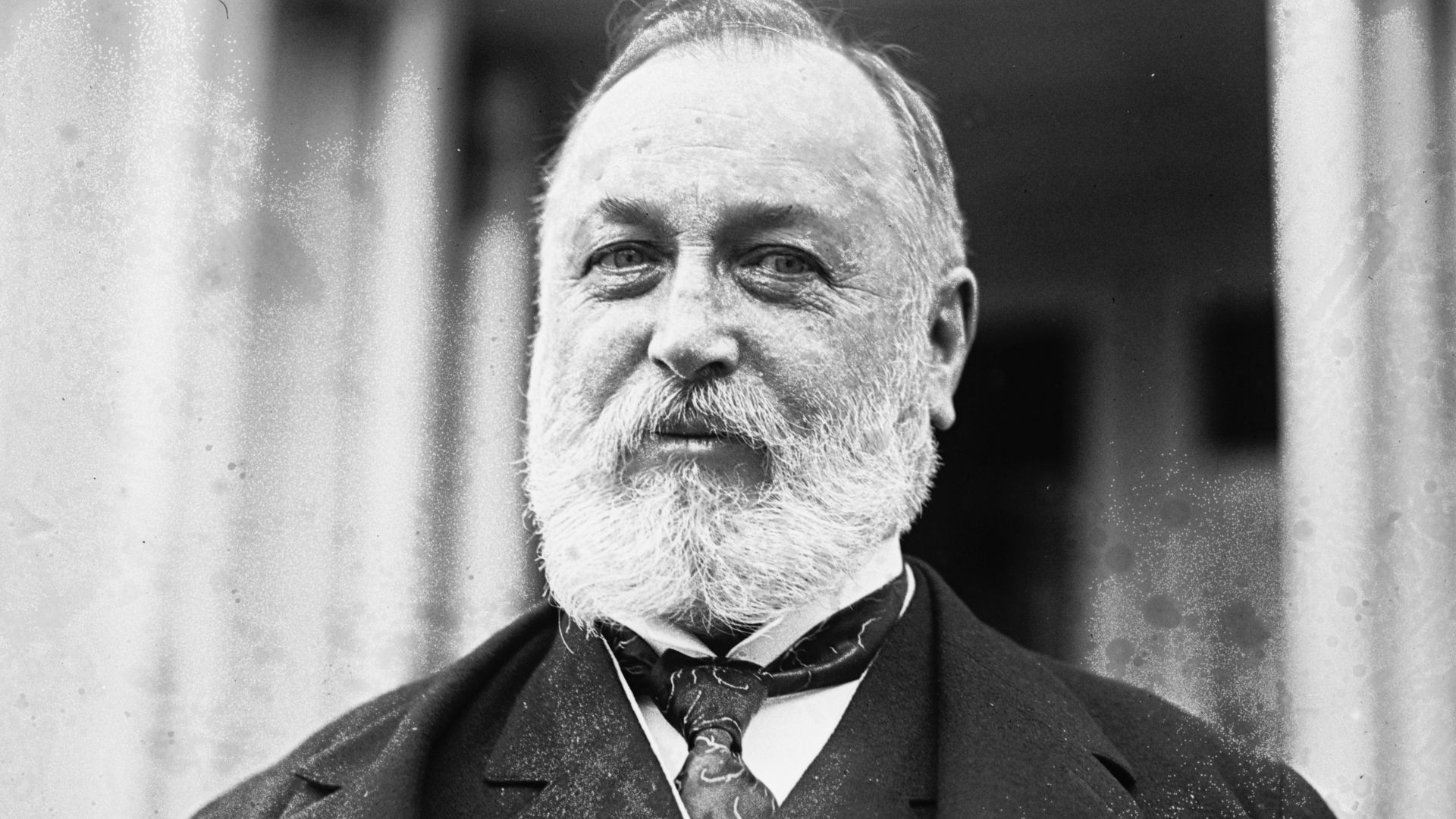

As Ponzi’s insane financial ascent continued, the Boston Post decided to investigate. They interviewed a financial journalist named Clarence Barron, who observed that Ponzi had not invested with himself. Barron also calculated that to cover the investments in Ponzi’s SEC there would have to be about 160 million postal reply coupons in circulation. The actual number of coupons in circulation was about 27,000. They were formidable foils for each other—while Ponzi went on to be known for his investment scam, Clarence Barron went on to be president of the Dow Jones and worked at The Wall Street Journal. He's considered the founder of modern financial journalism and has a finance magazine named after him.

National Photo Company Collection, Wikimedia Commons

National Photo Company Collection, Wikimedia Commons

13. First Run

The Post piece caused panic amongst investors, and Ponzi paid out $2 million over three days to crowds outside his office. However, he was far from admitting defeat—he’d mingle with the crowds, offering coffee and donuts, and some in the crowd decided to leave their money invested with him.

14. Second Run

Ponzi decided to hire a publicity agent, William McMasters. However, McMasters became suspicious of Ponzi and investigated his finances. In August, the disloyal agent wrote an article for the Post declaring Ponzi to be $4.5 million in debt. This sparked a second run on the SEC from worried investors, who Ponzi paid off in one day.

15. Robbing Peter to Pay Paul, and Borrowing From Hanover Trust

After the second run, an investigation by the state’s Bank Commissioner, Joseph Allen, discovered that Ponzi had borrowed about $250,000 from Hanover Trust—a bank that Ponzi effectively controlled. While not cause for criminal charges, this led Allen to assign state examiners to supervise Ponzi’s accounts. The state examiners would eventually determine that Ponzi was $7 million in debt.

16. A Bad Day

On August 11, 1920, the Post ran a story detailing Ponzi’s Montreal misadventures in corrupt banking and check fraud. Later on in the day, Allen seized Hanover Trust, foiling Ponzi’s contingency plan to ‘borrow’ money from the bank’s vault.

Almanac: Charles Ponzi and his Ponzi Scheme,(CBS Sunday Morning ), CBS News Productions

Almanac: Charles Ponzi and his Ponzi Scheme,(CBS Sunday Morning ), CBS News Productions

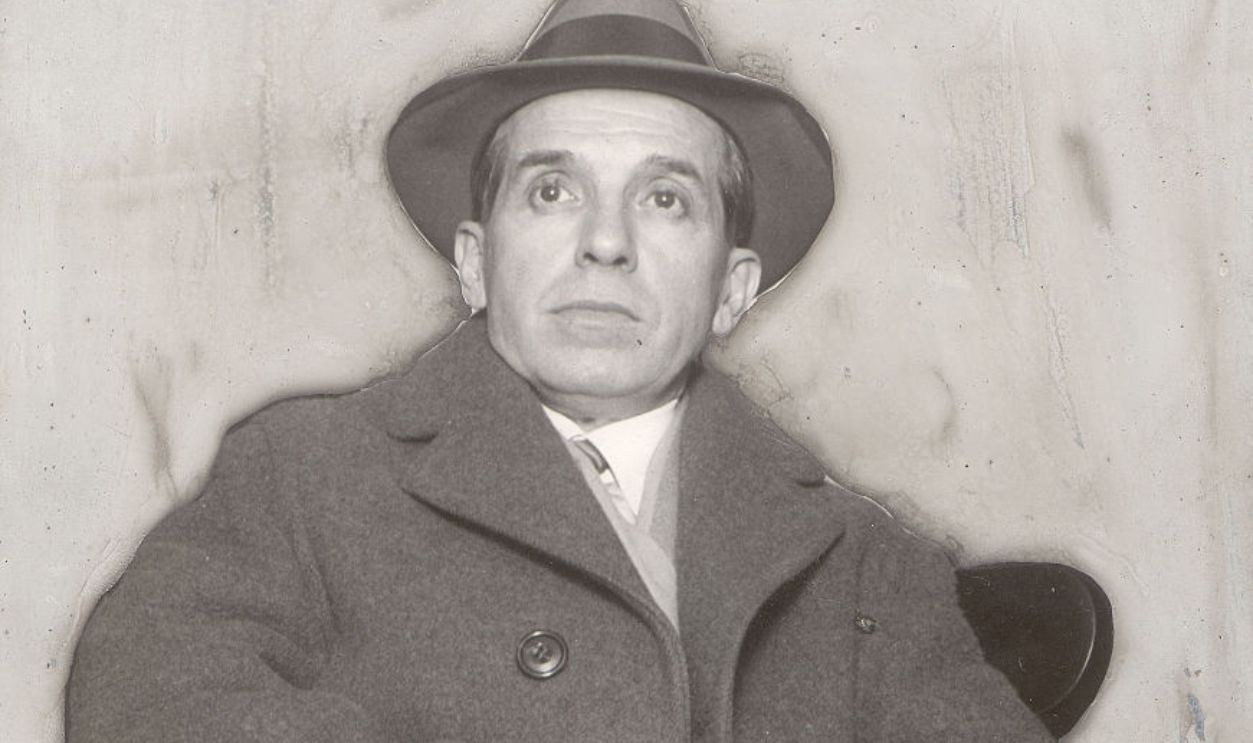

17. Not a Better Day

On August 12th, Ponzi surrendered himself to authorities and was charged with mail fraud. After being released on bail he was re-arrested on charges of larceny.

18. Also Not a Good Day for Investors

After the collapse of Ponzi’s SEC, Hanover Trust, and five other banks, investors retrieved less than 30 cents per dollar invested. The total investment losses were estimated at $20 million, or $240 million calculated for inflation.

19. A Third Bid

Charged with 86 counts of mail fraud by the Feds, Ponzi pled guilty and was given a relatively lenient sentence of five years.

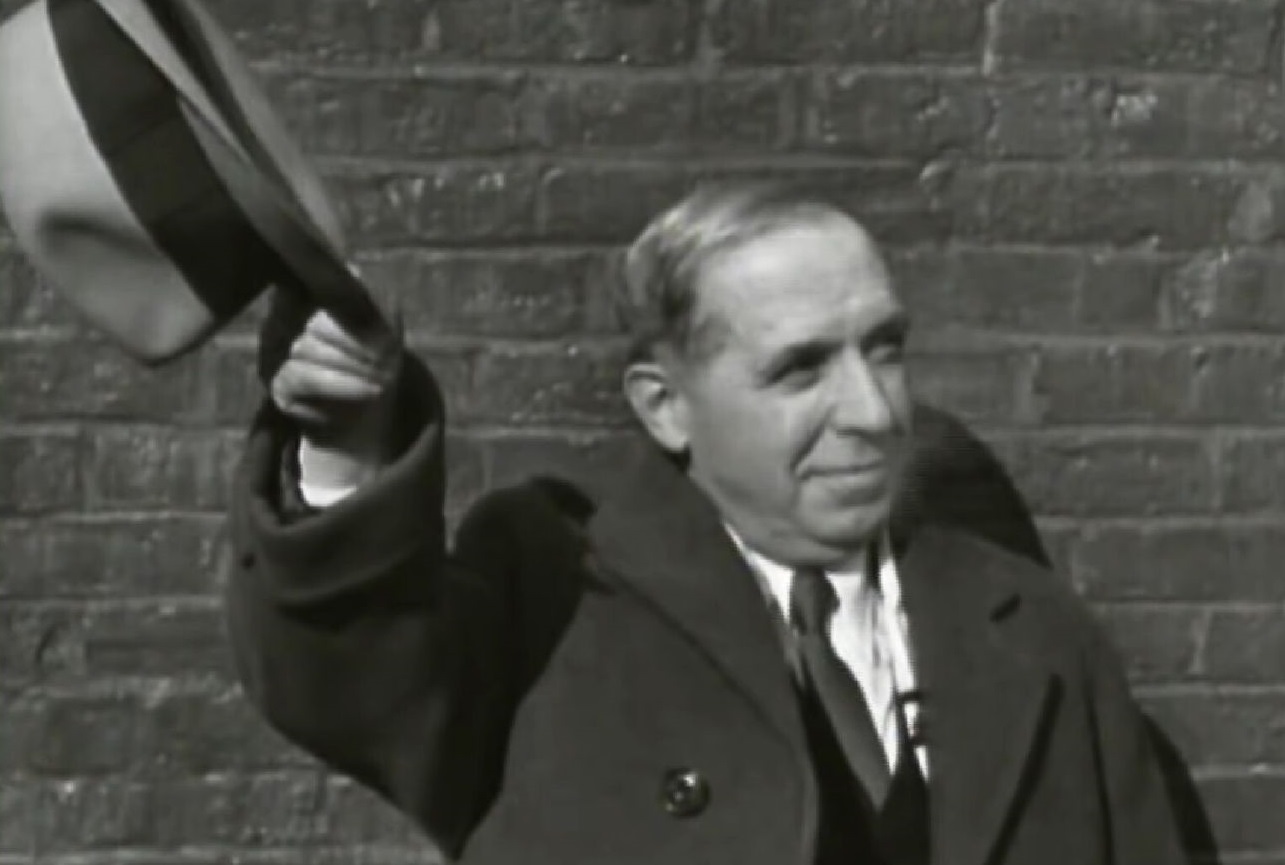

20. Not So Fast Buddy

Ponzi was able to get out of jail after just three and a half years but was almost immediately indicted on 22 state charges of larceny.

Almanac: Charles Ponzi and his Ponzi Scheme,(CBS Sunday Morning ), CBS News Productions

Almanac: Charles Ponzi and his Ponzi Scheme,(CBS Sunday Morning ), CBS News Productions

21. The Trial(s)

After arguing that the state’s charges were in bad faith as they exemplified double jeopardy, and having his arguments dismissed, Ponzi represented himself in a trial for the first ten counts of larceny. Apparently, his powers of financial persuasion were transferable to the judicial system, as he was acquitted on all counts by the jury. A second trial, for the next five charges, found a deadlocked jury, and so it took a third trial to convict Ponzi on the remaining seven counts, and he was sentenced to seven to nine years in jail.

22. FIN

Ponzi would scam again, in Florida, after his larceny conviction, then attempt to flee the country. After this failed, he served another seven years in prison in Massachusetts, but ultimately made it back to Italy, where he died.

23. Final Statement

You might think that he would have shown some remorse, but while giving a final interview to an American reporter, Ponzi said "Even if they never got anything for it, it was cheap at that price. Without malice aforethought, I had given them the best show that was ever staged in their territory since the landing of the Pilgrims! It was easily worth fifteen million bucks to watch me put the thing over." I'm not sure his victims would agree.

Underwood Archives, Getty Images

Underwood Archives, Getty Images

24. PostScript

Almost 60 years after the death of Ponzi, one of the biggest stories of the last decade told a similar tale of financial hubris. This investment scandal with a similar structure would be discovered to be the work of Bernie Madoff. The former NASDAQ chairman admitted that the investment arm of his firm was an elaborate Ponzi scheme, and investors lost an estimated $18 billion.

You May Also Like:

Crooked Facts About Modern-Day Swindlers

Anna Sorokin Swindled New York's Rich And Famous

Tricky Facts About Con Artists