Of all the tragic Hollywood stories—and there are a lot—the story of Audrey Munson may well be the most devastating. Many consider Munson to be the first supermodel, but instead of posing in the latest fashions for the camera, she was standing still for sculptors. It was when Munson tried to parlay her fame into a movie career, however, that things went south. There was no quick crash and burn for Munson, and a devastating series of events led her to a truly dark and unforgettable end.

1. She Had A Disturbing Prediction

Audrey Munson was born in Rochester, New York on June 8, 1891. By the time she turned eight, Munson experienced two major misfortunes. First, her father abruptly divorced her mother and left them. Then, a psychic made an ominous—and accurate—prediction for her future. While the fortune teller saw that Munson would be famous, she also told her that when Munson found happiness, it would “turn to ashes in your mouth”.

That’s a lot for a kid to take in. Worse still, it was completely true.

2. She Played A Guy

After the divorce, Munson and her mother needed a change, so they moved to Providence, Rhode Island and then to New York City. Once in the Big Apple, Munson set her sights on a career in show business. She soon got her first break, but it was an odd one. The play was The Boy and the Girl, but Munson played neither a boy nor a girl: her part was that of a footman.

It didn’t matter, because the play was on Broadway and it would certainly lead to bigger things.

3. She Was Discovered

It turned out that appearing in a bit part on Broadway led to absolutely nothing. What got Munson famous was something most of us do on a daily basis: shopping. While she and her mother were window shopping, they met Felix Benedict Herzog. Herzog was a photographer and stated that he wanted to take Munson to his studio and photograph her.

For some reason, Munson’s mother didn’t grab her daughter and run away from this potentially dangerous man. Instead, the three of them went to Herzog’s studio and changed Munson’s life forever.

4. He Shared Her

Herzog took photos of Munson—and found something extraordinary in them. There was something about this young girl, and Herzog didn't waste a moment: he quickly brought her to the attention of his friends. Once they met her, Herzog’s group of associates—sculptures, painters and muralists—seemed to share Herzog's obsession with Munson. They all wanted to use her in their work.

5. She Was Perfect

But what was it exactly about Munson that artists couldn’t get enough of? All of them agreed that Munson had perfect “Grecian” proportions. Some even called her the latter-day Venus de Milo—referring to the Greek statue of the goddess of love. Besides her physique, Munson had something else in common with Venus de Milo: back dimples.

This was an extremely rare feature and one of the artists even told Munson she had to “guard those dimples”. Soon it would be impossible for Munson to guard anything—she’d be all over New York City.

6. She Inspired Him

One artist that Munson captivated was Isidore Konti—a sculptor from Austria. When Munson met Konti, she’d already done a few stints as a model. Konti was making a sculpture for the Astor Hotel and it was going to be very prominently displayed in the lobby. Konti used The Three Graces by Antonio Canova as his inspiration for the sculpture.

There was only one problem: none of these graces was wearing any clothes.

Wikimedia Commons Isidore Konti

Wikimedia Commons Isidore Konti

7. She Got Unveiled

Munson was comfortable posing for photographers, painters, and sculptors—but with her clothes on. When Konti approached her to pose as all three graces in his sculpture for the Astor Hotel, she was faced with a difficult decision. She was just 18 years old. Could a woman as young as this feel comfortable enough to take it all off for the sake of art?

Apparently, the answer was yes. The hotel unveiled the sculpture in September 1909 and even acknowledged Munson as the muse. She had just turned 19.

8. She Was Kind Of Plain

It’s hard to see Munson as a mega-celebrity like Sarah Bernhardt, because she didn’t play the game when she wasn’t working. With her clothes on, Munson looked rather plain. She didn’t wear corsets to squeeze her body into the fashionable shape of the day or even wear high heels. Instead, Munson preferred dresses that were practical and natural.

She just happened to think that her body looked good undressed and felt no prudishness at posing for artists. It turned out that Munson wasn’t the only one to think her body looked good.

9. She Was Everywhere

Once word got out that Munson was available as a model—and especially as one who would pose uncovered—she became immensely popular. Sculptors were clamoring over each other in order to work with Munson. Not only that, once the artists finished their work, Munson had to have noticed something: her image was all over New York City. Unfortunately, this left her incredibly vulnerable.

Munson’s popularity was out of control—and someone close to her was concerned and thought she needed protecting.

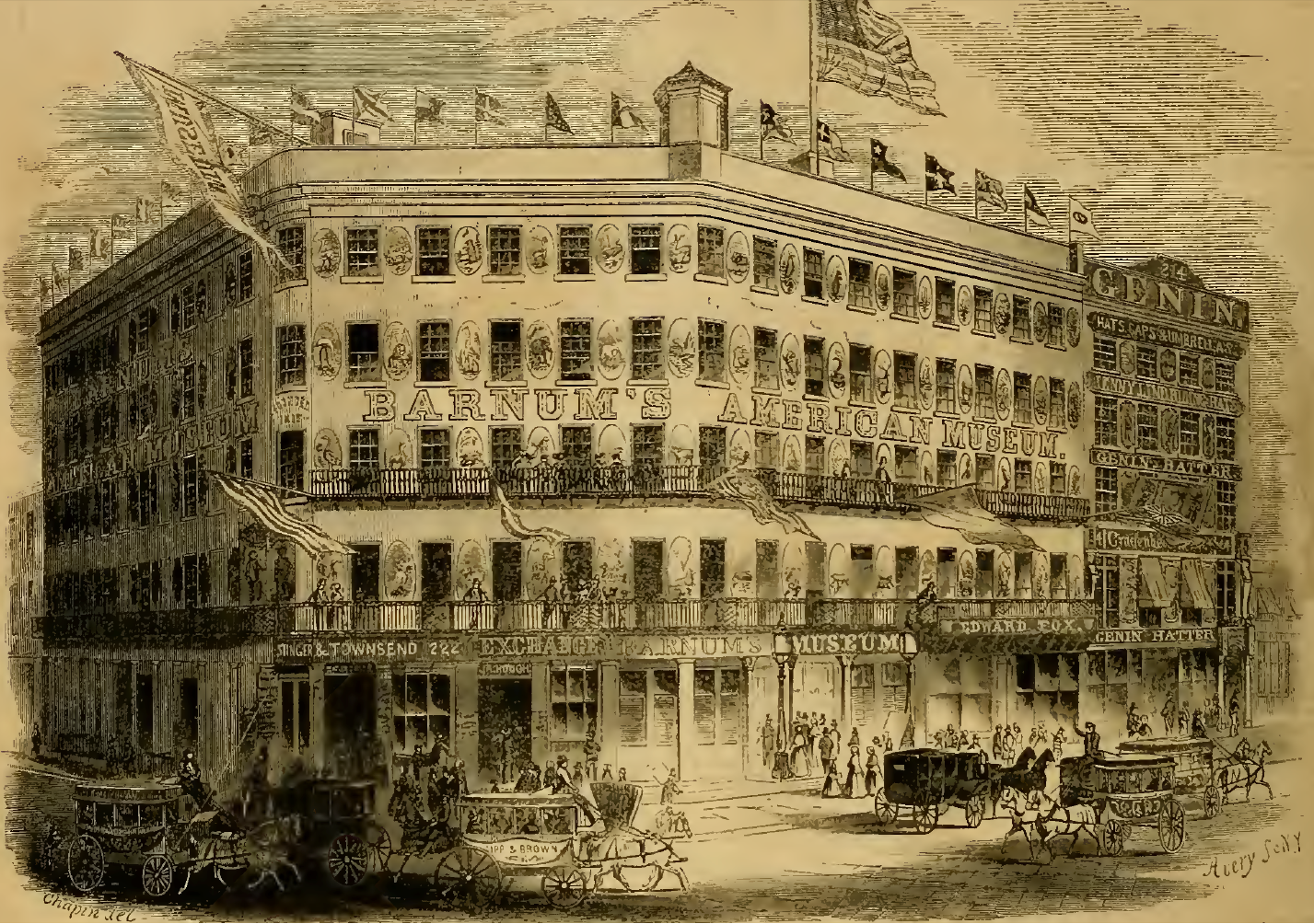

Gleason’s Pictorial, Chapin, Avery., Wikimedia Commons

Gleason’s Pictorial, Chapin, Avery., Wikimedia Commons

10. She Needed Protection

Herzog, when he’d first discovered Munson, likely had no idea what a whirlwind she was in for. When he’d met her, she’d literally been walking down the streets of New York, and now statues in her image looked down on those very streets. Herzog, while proud of his protege, also felt protective of her. He did, however, show this in an odd way: He asked her to marry him.

11. She Was Way Too Young

When he proposed, it was unclear whether Herzog was in love with Munson or simply offering protection. What was clear was that he was over 50 years old and she was just 21. Munson, on her part, was actually considering accepting the proposal from her much more senior mentor. Before she could say yes, however, Herzog got a call from his doctor that put his proposal on hold.

12. She Got Time To Think

Herzog’s doctor was calling to tell Herzog that he needed intestinal surgery. For Munson, this surgery was a godsend: it gave her time to think. Did she really want to have a husband who was decades older than her? Wasn’t there someone out there around her own age that she’d have more in common with? Munson was still leaning toward accepting Herzog’s proposal when something happened that made her mind up for her.

13. She Got A Name

As Munson contemplated Herzog’s proposal, tragedy struck. Herzog didn’t survive the surgery. However, this may have been for the better as this marriage seemed destined for failure. Besides, Munson was the toast of the town as statues carved in her image were popping up everywhere. She was on freestanding works, monuments, and even some state capitol buildings.

One hundred artists got together and decided to give her a name: they called her “Miss Manhattan”. Munson, however, wouldn’t stop at Manhattan—she was ready to take on the entire country.

14. He Wanted Her

In 1915, San Francisco was hosting the Panama-Pacific International Exposition which had as its stated purpose: a celebration of the opening of the Panama Canal. The real reason, however, was to showcase San Francisco’s recovery from an earthquake in 1906 and bring back tourists. The lead sculptor of the exhibition was Stirling Calder and there was one thing he desperately wanted for his sculptures: Audrey Munson.

15. She Almost Hit A Hundred

One of Calder’s larger works for the exhibition was the Court of the Universe. Calder had a grand vision for this building: none other than St Peter’s Square in the Vatican. Upon its completion there were 90 figures based on Munson's body on the colonnades of the building. If this fact didn’t go to Munson’s head, the total number of Munson’s images might just do the trick.

16. She Got A New Nickname

Once the exhibition in San Francisco took place, there were an astonishing number of sculptures in Munson’s image. In the end, three fifths of the sculptures at the exhibition were from Munson’s poses. This gave her yet another nickname: “Panama-Pacific Girl”. Munson had seen her image depicted in paintings, photographs and sculpture: it was now time for the public to see her body on film.

17. She Made A Shift

Maybe Munson grew tired of standing around while artists depicted her body, maybe she wanted to actually do something. In 1915, Munson decided to take her celebrity as a model and, like so many models after her, get into film. At this point in history, Hollywood films were just beginning their rise to popularity. This was the silent films era, and Munson wanted a piece of it.

18. It Wasn’t A Stretch

Munson’s first role in a film wasn’t much of a stretch: She plays a sculptor’s model. The film was called Inspiration—and it caused quite a stir. Munson appears without any clothes on. Most critics agreed that there wasn’t much of a plot—it follows an artist in search of a model. The scenes where Munson poses, however, are the real meat of the film. So it was clear: Munson could act. Or could she?

19. She Had A Double

While Munson was trying to shift her career from posing into acting, it turns out there wasn't much of a shift at all. The director wanted to leave the acting to a professional, and just get Munson to do the posing in her birthday suit. Wait a minute, isn’t it usually the opposite? In today’s Hollywood, some actors require a double to stand in when the clothing hits the carpet.

So why didn’t they want Munson to do the acting part? No one seems to know. Another bit of confusion with Inspiration is how the heck it got past censors.

20. They Changed Their Minds

The National Board of Censorship took a brief look at Munson’s Inspiration and gave it a pass—and didn’t even ask for any cuts. A few weeks later, the board realized what they had done and did an about face. Some members admitted that they may have approved the film too quickly. They wouldn’t reverse their decision on Inspiration, but they issued a warning to future films: if someone was cavorting around sans clothing, there had better be a good reason for it.

21. It Didn’t Pass

The censors had warned filmmakers against unnecessary undress, but this didn't stop Munson from doing it again. Her second film was 1916’s Purity. In this film, Munson does her own acting and appears as both Purity and Virtue. Again, Munson appears in the fim without any clothes on, but this time the censors were ready for it. Instead of giving Purity and easy pass as they had done with Inspiration, they came back to the filmmakers with a list.

Wikimedia Commons Still from the film Purity

Wikimedia Commons Still from the film Purity

22. She Had To Stand Still

The National Board of Review (NBR) had a list of changes they wanted made to Purity before theaters began to show it. The list had 10 grievances and they almost all involved Munson. The board didn’t like it when the film showed Munson removing her clothes, and they also didn’t like it when she moved around too much with no clothes. Inexplicably, they went on to complain about her neckline being too low. Her neckline? Didn’t this seem like the least of their worries?

23. It Was Mayhem

While the recommended cuts came from the federal government, it was up to each state to enforce them. Some states decided to show the film as it was—without the recommended edits. Some states made their own cuts and a few states, like Kansas, put an outright ban on the film. The NBR didn’t seem to appreciate the mayhem involving Purity and a lack of a consistent response to showing the film.

This led the board to make a decision for all future films: everyone had to have their clothes on.

24. She Partied

After just a few movies, Munson had had it with Hollywood and the censors. She kicked the dust of California off her heels and headed east. Here she partied in high society in New York City, Newport, and Rhode Island. But partying wasn’t all she was doing. Strangely enough, it appears that Munson may or may not have gotten married at this time. The alleged groom was Hermann Oelrichs Jr—the son of a wealthy silver miner. Oelrichs was at that time the richest bachelor in the world—not a bad catch for Munson.

There is, however, no record of this union. What there is a record of is a very strange letter that Munson wrote about Oelrichs.

25. She Got Angry

It’s not clear whether Munson married Oelrichs or not, but it is clear that he made her very angry. In a letter Munson wrote to the US State Department, Munson accused Oelrichs of ruining her chances at being a film star. She also said he was part of a network of people who were pro-Germany. Was Munson becoming unhinged?

At the end of the letter Munson suggested that she was through with America, and that she’d prefer to live in England.

26. It Was Time To Settle Down

Sadly, Audrey Munson never made it to England. By 1919, she was living in a Manhattan boarding house with her mother. This certainly doesn’t sound like a step up for the woman who had posed for so many pieces of art and appeared in films. Maybe Munson, even though she was only 28 at this time, was ready to settle down. Well, this certainly didn’t happen—not by a long shot.

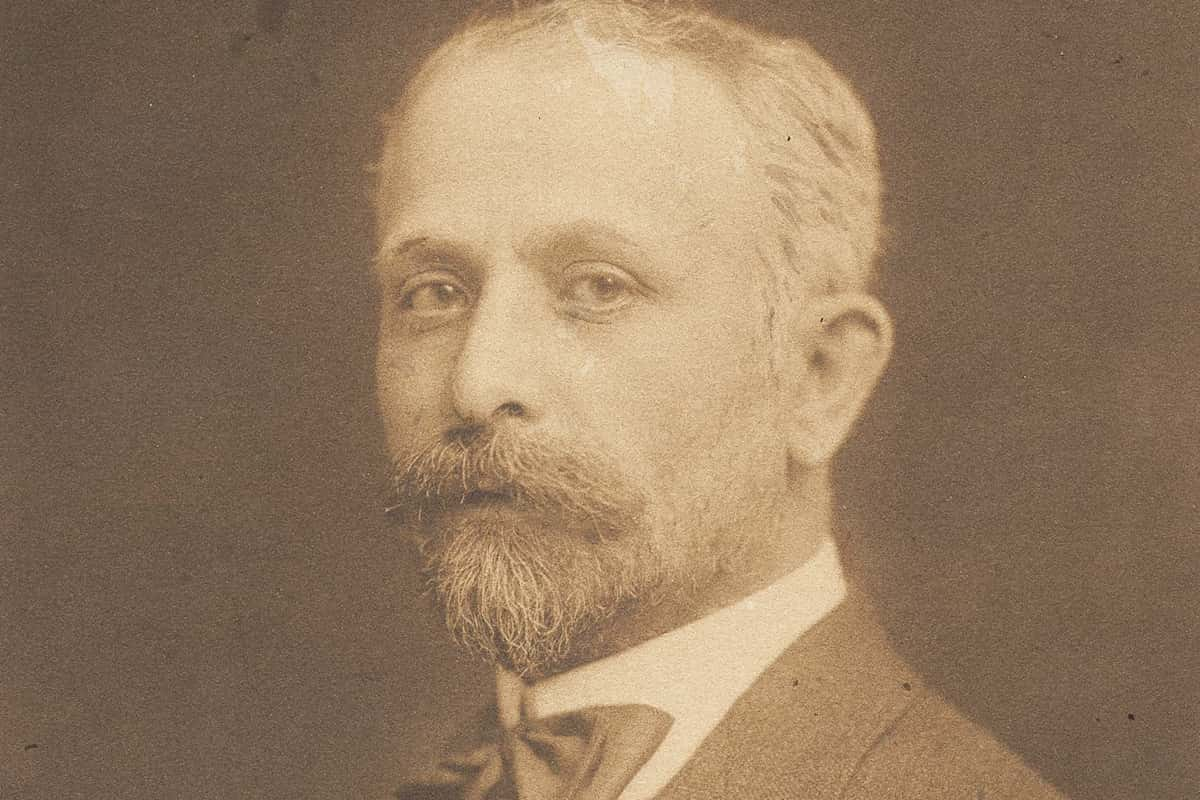

27. He Fell Hard

Once again, Munson’s beauty was causing a disruption to her life. The landlord at the boarding house, a Dr. Walter Wilkins, had fallen head over heels in love with Munson. There was one big problem with this. He was already married. For some reason divorce wasn’t an option for Wilkins, so he took a drastic step—one that would spell disaster for Munson and her mother.

Wikimedia Commons Dr. Walter Wilkins

Wikimedia Commons Dr. Walter Wilkins

28. She Made A Run For It

Munson’s landlord had fallen for Munson’s charm, and he was hoping to marry her. To make this happen he had to get out of his marriage. Instead of opting for a simple divorce, the doctor decided to do something much more disturbing. He liquidated his wife. When Munson saw what her doctor friend had done, she packed up her mom, and the two left town in a hurry.

29. They Hid In Fear

Once the authorities found out that Wilkins had offed his wife, they wanted to talk to Munson—except no one knew where she was. Authorities carried out a nationwide search as Munson and her mother hid away. Officers finally located the two in Toronto, Canada, and demanded they return to New York for questioning. Munson heard the demand and gave them a solid “no thank you”.

Well, if Munson wouldn’t come to New York for questioning, they’d bring the interrogators to her.

30. She Said It Wasn’t True

Because Munson and her mother were too frightened to return to New York, they were interrogated in Toronto. The NYPD used the Burns Detective Agency to ask the two women some questions about their relationship with Wilkins. While most of what Munson said to the officers was confidential, we do know one thing she said: there was no romance between her and Wilkins.

31. She Couldn’t Save Him

Whatever Munson said—or didn’t say—to the investigators did nothing to save Wilkins. He was found guilty and sent to the electric chair. But the story didn’t end there. Before he could get to the chair, however, Wilkins did something heartbreaking: he hung himself in his cell. It was a tragic end for Dr Wilkins—but not as tragic as for his wife. It was also, however, the beginning of the end for Munson.

32. She Fell From Grace

Munson’s association with the murderous Wilkins did nothing for her career as a model—well, it actually may have ended it. For some reason, Munson had fallen out of favor with artists. She was unable to find work, so she and her mother moved to Syracuse, New York. The two women needed money, so mom began a career selling kitchen utensils—door to door. Munson herself got a job taking tickets at a small museum.

Munson had clearly hit rock bottom—but things were just going to get worse.

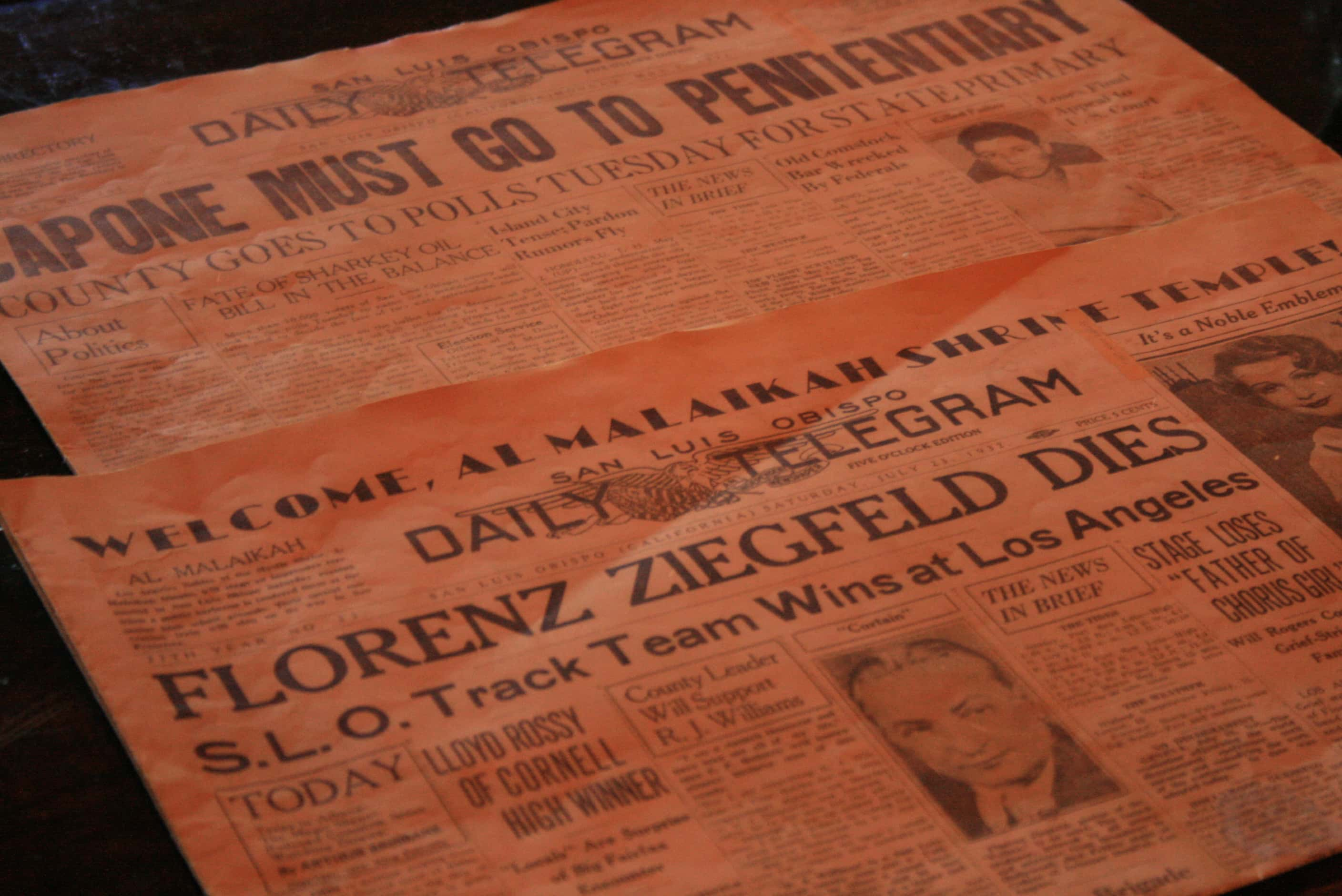

33. She Shared Her Story

The Hearst Sunday Magazine released 20 articles written by Munson about her career as a model for artists. Munson filled the articles with anecdotes about her life, and they served as a sort of cautionary tale to other women who were contemplating a career as a model. The articles were a big hit, but there was one thing wrong with them: Munson hadn’t written them.

34. They Ghosted Her

The story was much more scandalous than just a ghostwriter. It turned out that the Hearst Sunday Magazine had hired a writer to tell Munson’s stories—without her permission. To make matters worse, another writer, Robert Z Leonard, wrote a screenplay based on these stories and was planning to make a movie. These two men had basically taken Munson’s life in order to make money—and Munson wasn’t getting a single dime out of the deal.

35. It Got A Thumbs Down

Strangely, Munson agreed to appear in the film based on the articles that she hadn’t written. As in her previous films, they hired an actor to play the dramatic parts, and Munson just appeared as a model posing with no clothes on. The film was called Heedless Moths and it got a general thumbs down from critics. Photoplay magazine even went so far as to recommend audiences against seeing it—so as not to inflame censors to ban other more worthy films.

Munson had appeared in a flop—and she hadn’t even been paid for it.

36. They Proved It

The public found out that the producers of Heedless Moths hadn’t treated Munson very well and became outraged. To calm the masses, Allen Rock—an agent-producer—took a picture of a check written out to Munson worth $27,500. Rock then paid to have the picture of the check printed in newspapers and magazines. Here, the ads tried to say, we did pay Munson for her work—but they were hiding a dark secret.

The check was actually a fake.

37. She’d Had Enough

The fake check was bad enough, and then something worse happened. When they decided to create a live show to tour with the film, the producers invited Jane Thomas—the woman playing Munson—instead of Munson herself. Munson had finally had it, and she sued the producers for $15,000 and won. Munson knew how much money she could make touring with her film. So the following year, she did just that—with disastrous results.

Wikimedia Commons Jane Thomas

Wikimedia Commons Jane Thomas

38. They Exploited Her

In 1921, brothers Maxson and Benjamin Judell had an idea to capitalize on Munson’s fame. They got the rights to her film Purity and took it and Munson on the road. To garner new interest the Judells renamed the film Innocence and promised live poses by Munson at each screening.

Sadly, the Judell brothers weren’t in it for the art of it, they were exploiting Munson’s willingness to pose uncovered. This decision put Munson into a heap of trouble.

39. She Got Rounded Up

On October 3, 1921, Munson rolled into St. Louis with Benjamin Judell and prepared for a screening of Innocence at the Royal Theater. As per the plan, Munson took to the stage to give a free show of how she posed for famous sculptors. That’s when it all blew up in her face.

The audiences had their thrill, but someone else wasn’t as pleased: the authorities. They rounded up Munson and Judell and took them down to the station.

40. They Wanted To Lock Her Up

Officers had detained Munson and Judell, but what were they going to charge them with? It turned out that the authorities thought that what Munson was doing on stage was obscene. The officers were ready to lock them up in penal institution on an indecency charge. This certainly wasn’t the money grab that Munson had signed up for.

Luckily, both Munson and Judell were eventually acquitted and actually went back down to the theater and even finished out the week. This time, however, Munson kept her clothes on.

41. She Was The Original Bachelorette

Years before there was reality TV—or any TV for that matter—Munson had a novel idea for a controversial publicity stunt. She conducted a search, with the help of the United Press, to find a husband. The search crossed the country trying to find a suitable match for the women whose image artists across the country had used as a symbol of pure beauty.

A list of finalists finally appeared, naming eligible bachelors from such varying locations as Tucson, Arizona and Omaha, Nebraska. Now, all she had to do was meet them and make her choice.

42. She Spoiled It

The next part of Munson’s plan to find a husband was for her to visit each bachelor in their home city. As the organizers were making the preparations for the tour, Munson started having cold feet. Did she really want to meet a husband this way? Did she even want to get married at all? Before she started her tour of dates, Munson spoiled the publicity stunt and announced she no longer wanted a husband.

Little stunts like these weren’t doing Munson any favors—people started questioning her sanity.

43. She Created A History

Munson’s stunt to find a husband, her arrest in St. Louis—they were all adding up to a classic celebrity breakdown. She continued down this path and began to tell lies. The biggest one was about her background. Munson carefully fabricated a link to European aristocracy and renamed herself Baroness Audrey Meri Munson-Munson—a fake name if I ever heard one.

While making up a glamorous past seems innocent enough, her next move wasn’t.

44. She Blamed Them

Munson had a lot of trouble in her life, but for some unknown reason she chose to blame a specific group for her woes. To remedy her problem, she went to the US House of Representatives and asked them to pass a bill. And what was this bill going to be? She wanted protection from “being oppress by the Hebrews”. Clearly, Munson was losing it, and what she did next confirmed it.

45. She Didn’t Want To Live

Munson was obviously suffering from some serious mental health issues. It got so bad that on May 27, 1922, Munson swallowed bi-chloride of mercury. This was the same concoction that had taken the life of another silent film star and artist’s model Olive Thomas only a few years before—and she’d lost her life gruesomely, in great pain.

Luckily, unlike Thomas, Munson survived the ordeal. But what had caused her to swallow the dangerous solution in the first place?

46. She Bought The Farm

Clearly Munson was not happy with her situation, so she did the only sensible thing: she changed it. In 1926, she packed up her mom and moved to Mexico. Well…actually to a farm in an upstate town called Mexico, New York. Here, she planned to make a comfortable home for her mother, who now needed extra care. It was an extremely kind deed on Munson’s part, but mom repaid her for it in a horrifying way.

47. She Wasn’t Fit

It’s not entirely clear what happened on that farm in Mexico, New York, but on Munson’s 40th birthday her mother took a drastic measure. She asked a judge to have her daughter committed. It was supposed to be Munson taking care of her mother on the farm, but maybe that wasn't happening. Munson’s mother told the judge that her daughter was suffering from depression and schizophrenia. Munson’s future was in the judge’s hands.

48. They Sent Her Away

To prove her case, Munson’s mother had gotten two doctors to sign a certificate of lunacy. In the end, the judge in the case sided with Munson’s mother and sent Munson to the St. Lawrence State Hospital in Ogdensburg, New York. Tragically, it was there that Munson appeared to lose her lust for life. A former nurse remembers Munson as a quiet patient. The nurse revealed a heartbreaking detail.

In her opinion, Munson's only problem was that she was sad and certainly didn’t need to be in the hospital.

49. She Was Left Alone

After spending years as the most recognizable woman in New York City, Munson’s only visitor at the asylum was the one who had put her there: her mother. Once her mother passed in 1958, Munson had no one. There was an agonizing 25-year expanse of time where Munson didn’t have one single visitor.

Her quarter-century of loneliness was finally broken by Darlene Bradley. Bradley was Munson’s half-niece and had discovered that her aunt was still alive and in an asylum. After 25 years, Munson finally had a visit.

50. She Remembered Her Dimples

It’s difficult to imagine Munson’s mental state, being locked up for more than half her life. The nurse was bathing Munson and remarked on her back dimples—the ones people told her to protect so many years before. Munson smiled at the nurse and told her that she couldn't lose her precious dimples.

51. The World Forgot Her

It wasn’t until 1996, at the age of 106, that Munson lost her life—but the tragedy didn’t end there. She lost her life in anonymity. No one figured out who she was until 2016, when she finally got a headstone. It was on her 125th birthday.