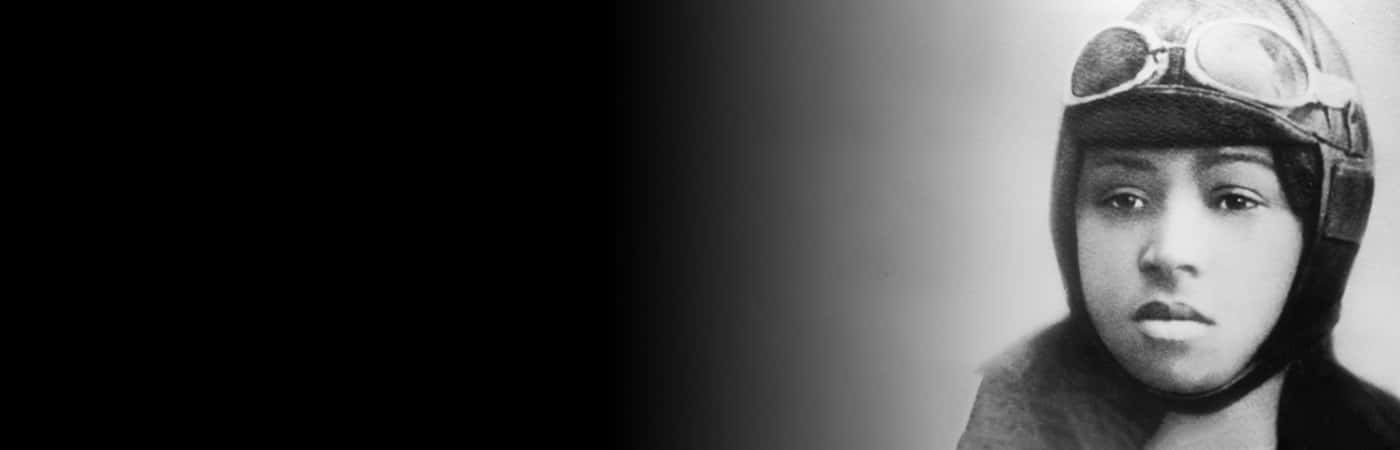

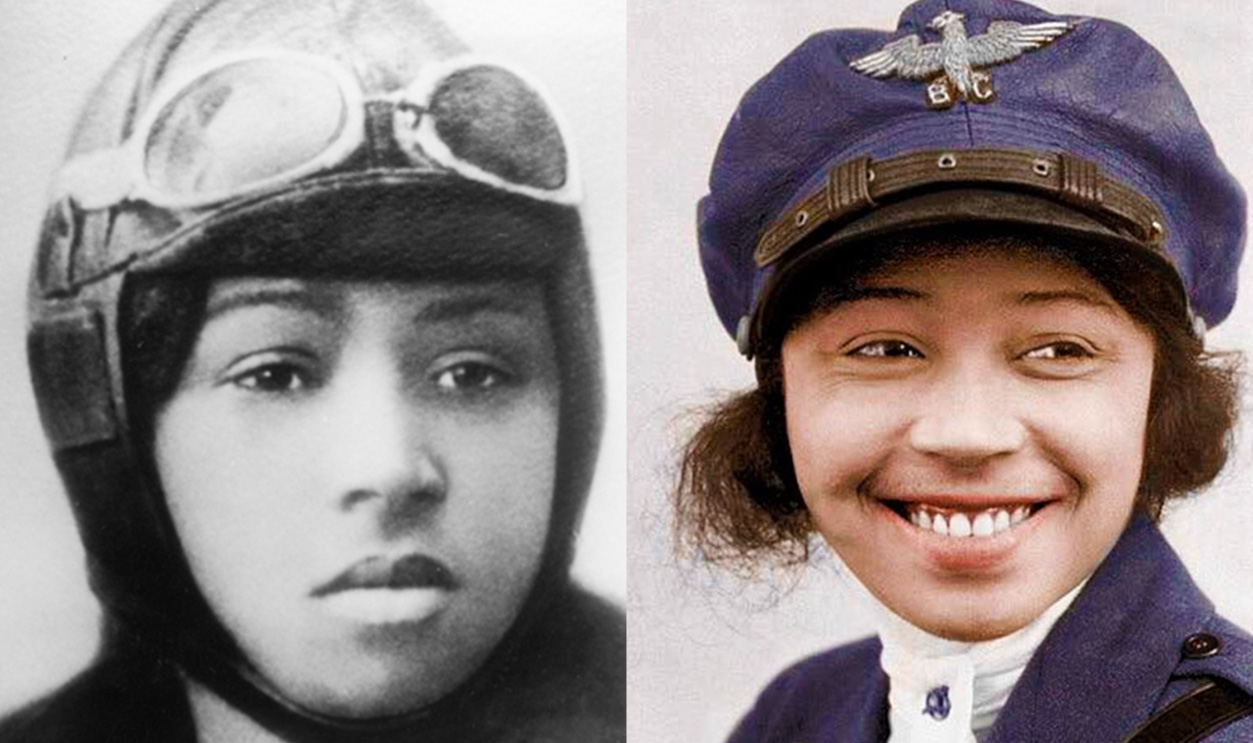

Bessie Coleman, The First Fly Girl

Intelligent, proud, and headstrong, Bessie Coleman didn’t just break barriers, she flew right through them. Coleman was widely recognized as one of the best pilots of her generation—so skilled that some audiences were willing to overlook the fact that she was a Black woman.

But Coleman never let them forget: She used her fame to promote civil rights, create space for Black people in aviation, and encourage a new generation of Black pilots. Here are daring facts about the one and only Bessie Coleman.

1. She Had a Double Heritage

Elizabeth "Bessie" Coleman was born on January 26, 1892, to Texas sharecroppers George and Susan Coleman. George Coleman’s grandparents were Cherokee, so Bessie was not only the first Black woman to fly, but the first Indigenous woman as well. Despite intense discrimination, Coleman never gave up and never gave in, proving that the skies belonged to everyone.

2. Her Mother Gave up Everything for Her

When Coleman was a child, her father left their home in Waxahachie, Texas, and returned to what was then known as Indian Territory in his home state of Oklahoma. Though he left expecting to find better work opportunities, Coleman’s mother chose not to join him. Instead, Susan Coleman worked to raise all thirteen Coleman children by herself. As we'll see, Bessie inherited her mother's determination and verve.

3. She Was Extremely Intelligent

Living in the segregated south wasn't easy for six-year-old Bessie. She had to rise each morning and walk four miles to her one-room schoolhouse. Once there, Coleman enjoyed school, only for harvest season to interrupt her studies. When the time came, Bessie had to put her education on hold and help her family pick cotton. Despite these hurdles, Coleman excelled. By the time she was 12, she got a scholarship to the Missionary Baptist Church School.

4. Her Dreams Were Crushed

Coleman had even bigger ambitions than going to high school. After graduating, she enrolled at Langston University. Even though Coleman had saved up all her money to afford tuition, it was only enough for one semester. Once her term was up, Coleman had no choice but to leave her studies...and then her life got even rockier.

5. She Had an Ill-Fated Romance

Around this time, Coleman married a man named Claude Glenn, and their relationship was twisted. While no one knows exactly what happened between them, it doesn't seem like their relationship was a love match. The newlyweds separated almost immediately, and in an icy move, Coleman never publicly acknowledged her husband. Ouch.

6. She Had Big Ambitions

With her college dream deferred, Coleman moved north to Chicago in search of work. Living with her brothers, she took a job as a manicurist. Sure, it paid the bills, but Bessie was looking for something bigger. She would soon find it.

7. Her Family Didn't Believe in Her

Coleman’s brothers returned from WWI with stories of the airplanes they had seen: fighter pilots and hobby planes and fearless aerial acrobats. In liberated France, even women were allowed to fly. Her brothers liked to tease the headstrong Bess; she could do just about anything she wanted, they said, but she’d never fly a plane. By now, Bessie Coleman had had just about enough of people telling her what she’d never do.

8. She Got Brutally Rejected

Coleman took a second job at a chili parlor, hoping to save up enough money for pilot school. Money, however, was not the problem. Coleman was a Black woman, two traits that, in 1920s America, did not fly—literally or figuratively. Coleman applied to flight schools all across the United States. Not a single one would take her.

The Legend: The Bessie Coleman Story,Gardner Doolittle Films

The Legend: The Bessie Coleman Story,Gardner Doolittle Films

9. She Never Gave up

Coleman’s story soon reached the desk of Robert Sengstackte Abbott, founder and publisher of the biggest Black newspaper in the country, the Chicago Defender. Abbott published a story about Coleman's rejections, launching a successful campaign to send Coleman to flight school to France. Soon enough, Bessie Coleman was taking French lessons and dreaming of her very first flight.

10. She Had Famous Teachers

In November, 1920, Bessie Coleman arrived at the Caudron Brothers School of Aviation in France. To say this was a big deal would be an understatement. The Caudron Brothers were France’s answer to the Wright Brothers. They taught themselves how to fly and eventually turned their hobby into a huge plane factory. Finally, Coleman was where she belonged...but the good times wouldn't last forever.

11. Her Life Flashed in Front of Her Eyes

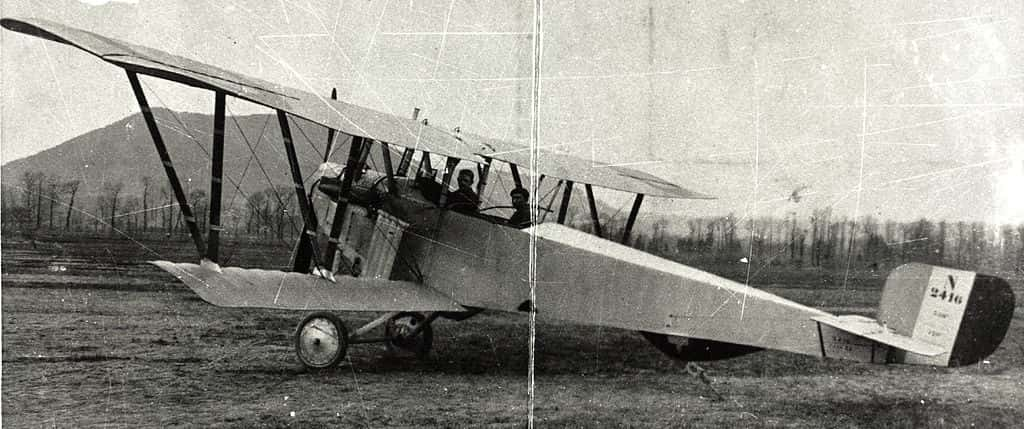

Coleman took her first flights in a Nieuport 82, a single-engine biplane built for combat during WWI. But there was one huge problem with the "Big Julies," as they were known: They were prone to failure. On one dark day, Coleman actually saw one of her fellow aviation students plummet to their end in one of these planes. Even so, Coleman stayed the course...but this would be a dark portent.

12. She Was a Cool Customer

When Coleman learned to fly in her Big Julie, the plane would often sputter for a few brief, terrifying moments, but even then, she never let her nerves stop her.

The Legend: The Bessie Coleman Story,Gardner Doolittle Films

The Legend: The Bessie Coleman Story,Gardner Doolittle Films

13. She Was the First

On June 15, 1921, Coleman completed her training and earned her pilot’s license, becoming the first Black woman, and the first Indigenous woman, to become a fully licensed pilot. Furthermore, because her license was issued by the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale, she became the first Indigenous person and the first Black person of any gender to earn an international pilot’s license. She made history twice in one day, but still, she wanted more.

The Legend: The Bessie Coleman Story,Gardner Doolittle Films

The Legend: The Bessie Coleman Story,Gardner Doolittle Films

14. She Earned Glorious Nicknames

Over the course of her brief time in the sky, Bessie Coleman earned a reputation for her flamboyant, daredevil flying style. Thanks to her dazzling flights, Coleman also earned some appropriately extravagant nicknames. Coleman's adoring fans called her Queen Bess, Brave Bessie, and "The Only Race Aviatrix In The World".

15. She Had a Training Montage

In the days before commercial passenger flights, the real money was in stunt flying. Coleman was a great pilot, but she needed to learn some tricks. There was just one problem: pilot schools in Chicago either didn’t teach stunt flying, or wouldn’t teach it to Bessie Coleman. Once again, Coleman travelled to Europe, looking for a teacher. She found one—no less than Anthony Fokker, founder of the famous warplanes which bear his name. Coleman spent spring and summer of 1922 studying with Fokker’s staff and returned home, determined to be the most exciting pilot in America.

16. She Gave Back

Flying wasn’t the only thing keeping Coleman in France. She stayed just long enough to participate in the second Pan African Congress. The Pan African Congress, organized by legendary figures WEB Dubois and Ida Gibbs Hunt, assembled Black delegates from across the world to advocate for the decolonization of Africa and an end to racism.

17. She Made a Triumphant Return

Upon returning to the United States, before she ever climbed into the cockpit and took to the skies over America, Bessie Coleman was already a celebrity. Reporters greeted her at the port, eager to learn more about this Black female pilot. The cast of the Broadway show Shuffle Along gave Coleman a special award for her contributions to the Black community.

18. She Had Daring Tricks

Coleman gave her first performance on Labour Day, 1922, at Curtiss Field, Long Island, New York. She was joined by "The Black Eagle," Hubert Julian, a Trinidadian-Canadian aviator who performed parachute jumps while playing the saxophone!

19. The People Went Wild for Her

Coleman’s first performance was a smashing success. To supplement her wages, Coleman stuck around after the show, offering curious spectators the opportunity to fly with her. A quick spin around the airfield cost $5, a hefty sum back in the 1920s.

20. Her Family Were Proud of Her

Coleman performed again just six weeks later in front of a hometown crowd at Chicago’s Checkerboard Airdrome. This performance was particularly special: among the 2,000-strong crowd were Coleman’s family, including her mother, sisters, and nieces. Coleman was thrilled to have her family present—in no small part because of her secret plan...

21. She Peer-Pressured Her Sister

Coleman thought she could persuade her sister, Gloria, to make a parachute jump. Bessie went so far as to get a red, white, and blue jumpsuit made for her sister, and even ran newspaper ads announcing the jump. Imagine Gloria’s surprise; she had been neither trained for, nor told about, Bessie’s plan. With perhaps less courage, though a good deal more common sense, Gloria informed Bessie she would not be jumping out of an airplane that afternoon, and the star-spangled jumpsuit went into the trash.

22. She Made a Heartbreaking Tribute

Coleman would give further performances in Gary, Memphis, and Boston. The latter she dedicated to Harriet Quimby, the first woman to receive a pilot’s license and the first to fly over the English Channel. Sadly, Quimby wasn't alive to see Coleman's tribute. She had perished in a 1912 plane crash in Massachusetts. Coleman didn't know it at the time, but she'd face an eerily similar fate.

23. She Was an Ace Flyer

Coleman dazzled audiences with her daring aerial manoeuvres. Figure 8s, loop-de-loops, dives and climbs—Coleman could do it all. She even did parachute jumps. Huge crowds turned out to see the woman now billed as "Queen Bess, the World’s Greatest Woman Flier" and it wasn’t long before Hollywood took notice of her.

24. She Turned Down Movie Stardom

Soon enough, Coleman hit the big time. She was offered a role in the movie, Shadow and Sunshine. Eager to promote her flying show and make enough money to open her own flying school, Coleman jumped at the opportunity. But she bowed out of the production when she saw the script. Coleman’s character, an indigent woman in tattered rags, struck her as stereotypical and derogatory; she refused to play her.

25. She Wrote Her Own Story

Coleman, evidently, had better ideas for a movie. In 1926, she wrote to film producer RE Norman, proposing a movie about her own life. Coleman hoped the biopic would be titled Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow. Sadly, fate would prevent the film from ever being made.

26. She Took a Stand

Her refusal to appear in Shadow and Sunshine was just one example of how Bessie Coleman used her talent and popularity to support equal rights. She absolutely refused to perform for segregated audiences, and was always willing to share the spotlight with other Black aviators and performers. Between airshows, Coleman would give lectures on aviation and civil rights in schools and churches.

27. She Wanted to Teach

Coleman’s ultimate goal was to open a flight school of her own, one that would accept Black women. She never forgot the feeling of being turned away from flight schools in America, and didn’t want anyone else to feel such discrimination.

The Legend: The Bessie Coleman Story,Gardner Doolittle Films

The Legend: The Bessie Coleman Story,Gardner Doolittle Films

28. She Went Under New Management

After an airshow in Gary, Indiana, Coleman met David Lewis Behncke, the future president of the Air Line Pilots Association. Behncke had learned to fly during the war and used that skill to establish a successful airfreight business. Behncke was well-known, well-connected, and owned a fleet of his own airplanes; when he offered to act as Coleman’s manager, she readily accepted.

29. She Flew for a Tragic Reason

Coleman's love of flight has heartbreaking roots. She often said, and truly believed, that "the air is the only place free of prejudices".

30. She Had a Bitter Breakup

The partnership with Behncke did not last long. Behncke did not want Coleman flying in the segregated south, where Jim Crow laws and hostile crowds could make it very risky to operate. Ever undaunted, Coleman insisted. Coleman relieved Behncke of his duties and bravely moved her base of operations from Chicago to Houston.

31. She Was a Boss Woman

Coleman found Behncke’s replacement very handy. Her new manager and publicity agent, William Wills, just happened to be her mechanic, too. Unfortunately, their collaboration was doomed to an utterly tragic end.

32. She Had Famous Friends

With all that time she spent in the sky, Coleman was bound to make friends in high places. Coleman moved in the same social circle as actors, dancers, musicians. Even the occasional prince would drop in. Coleman was close friends with dancer-singer extraordinaire Josephine Baker. Inspired by Coleman, Baker got her own pilot’s license in 1933.

33. She Had a Strange Job

As a young girl, Coleman made money by working as a manicurist. Such was her speed and precious that she became known as the fastest nail painter in Chicago. Year later, when Coleman moved to Orlando, she returned to her roots by opening a beauty salon. She used the business to save up enough money to open her flight school and buy her own plane.

34. She Loved "Jenny"

Flying was an expensive pastime, and Coleman tried to save money wherever she could. Usually, she resorted to just borrowing a plane for her performances. By 1923, Coleman had finally saved up enough money to buy her very own plane—a Curtiss JN-4 "Jenny" with an eight cylinder OX-5 engine and a ceiling of 6,500 feet. Sadly, Coleman’s delight would be short-lived.

35. She Survived a Plane Crash

During one 1923 performance, Coleman's love for the skies brought her into a world of fiery danger. As she flew her brand-new biplane in front of a crowd of 10,000 people, the machine suddenly cut out. It smashed into the ground, breaking to splinters. "Brave Bess" limped away from the crash with a broken leg and a few cracked ribs. It took a year for Coleman to recover, but she was lucky to survive at all. But that didn't mean she was out of the woods.

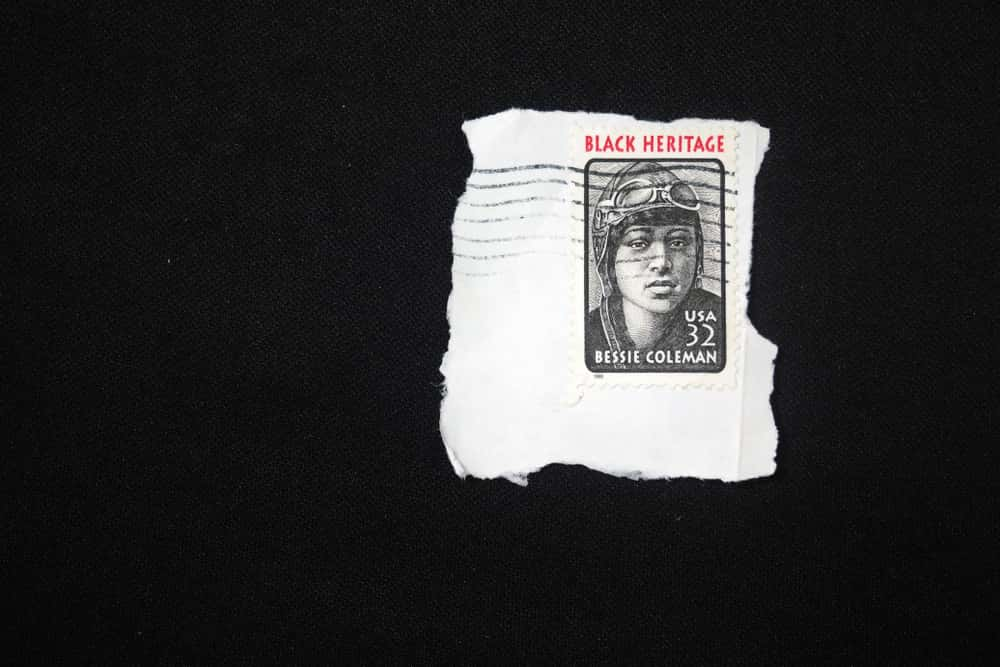

36. History Remembers Her

Coleman has received a slew of honors for her barrier-breaking contributions to flight. Her hometown of Waxahachie, Texas, named a street after her, and a middle school in nearby Cedar Hills, Texas, is named in her honor. In 1995, the United States Postal Service released a Bessie Coleman stamp as part of their Black Heritage series.

37. She Was in Good Company

Coleman wasn't the only Black pilot during American's Jazz Age. Eugene Jacques Bullard had flown for France during WWI, winning the Croix de Guerre, before he was grounded by order of the US government. James Banning earned a pilot’s license in America after taking lessons from a private tutor. Their own struggles and accomplishments notwithstanding, none of Coleman’s male predecessors earned her credentials, displayed as much raw talent, or garnered so much attention.

38. Her Peers Adored Her

Even though Col3man was the pinnacle of her profession, her fellow Black pilots didn't feel jealous of Coleman or resent her success. On the contrary, Coleman inspired Black pilots to climb higher in their field. William J. Powell, another Black aviation pioneer, actually named his pilots’ club the Bessie Coleman Aero Club as a tribute to her.

39. She Got a Famous Memorial

On January 26, 2017—the 125th anniversary of her birth—Coleman received one of the highest honors that can be bestowed on a person. To celebrate her birthday, and her contributions to aviation, Goggle made Coleman the subject of that day’s Doodle.

40. She Went Into Space

In 1992, astronaut Mae Jemison became the first Black woman in space. As she rocketed into orbit, she carried with her a picture of her inspiration, Bessie Coleman.

41. Her Name Lives on

In 1929, William Powell founded his Bessie Coleman Aero Club. Their first order of business: to finally realize Coleman’s dream of a flying school for Black pilots. The school’s chief instructor was Coleman’s great admirer, James Banning.

42. She Was Almost Forgotten

While Coleman’s passing shook the African American community, it went largely unremarked upon by the white media. In 2019, the New York Times finally published an obituary for the pioneering aviatrix in their "Overlooked" column.

43. She Made a Rash Decision

In 1926, Coleman purchased a new plane, another Curtiss JN-4, from a seller in Dallas. The JN-4 was Coleman’s preferred model, but this one was in such rough shape that her mechanic, William Wills, had to stop five times while flying the plane back from Dallas to Jacksonville. He begged Coleman not to use the plane, but Coleman wanted to test it for herself. It was a huge mistake.

44. She Forged Ahead

With Wills at the wheel, Coleman went up and began planning the next day’s airshow. After all, she'd done it so many times before, what was there to worry about? But just ten minutes into the flight, disaster struck.

45. She Had a Final Flight

As the plane began to spin out, Coleman was thrown from her seat. She plummeted toward the ground, while Wills desperately worked to regain control of the plane. He was unsuccessful; unbeknownst to either Coleman or Wills, a wrench had wedged itself into the engine. The plane ploughed into a Florida field, killing Wills immediately and burning his body the wreckage. But Coleman's fate was much darker.

46. Her Crash Has a Untold Story

The crash was a terrible tragedy for most of the flying community. For one man, it was a close call. John Betsch, the recent Howard University graduate who had organized the Jacksonville airshow, had initially agreed to go up as Coleman’s passenger for another test flight before the show...and he might have been guilty of one part of the accident.

47. Her Accident Wasn't Innocent

It has been suggested that Betsch himself, while not responsible for the crash, was responsible for the fire that incinerated Wills’ body. Shocked by the sight of the crash, Betsch allegedly dropped his lit cig into a pool of gasoline. The fire travelled directly back to the wreckage, and soon the flames engulfed the whole scene.

48. Her End Was Tragic

Bessie Coleman, Brave Bess, fell 2,000 feet through the air while the plane was still weaving out of control and died on impact with the ground. She was just 34 years old. Yet this isn't even the end of the story.

49. The World Mourned Her

Mourners put on a funeral service Coleman in Florida before her body went back to Chicago for burial. At a memorial ceremony in Chicago, more than 10,000 people turned out to bid Coleman farewell. Representatives of the US Army’s 370th Infantry—formerly known as the African American Eighth Infantry—served as her pallbearers.

50. She's Part of a Tradition

Bessie Coleman now lies at Lincoln Cemetery, Chicago. Since 1931, it has been a tradition for members of the Challenger Pilots’ Association, Chicago’s first Black flying club, to fly over Coleman’s grave and drop flowers.

Sources: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16