"'Those darling byegone times, Mr Carker,' said Cleopatra, 'with their delicious fortresses, and their dear old dungeons, and their delightful places of mistreatment , and their romantic vengeances, and their picturesque assaults and sieges, and everything that makes life truly charming! How dreadfully we have degenerated!'" —Charles Dickens, Dombey and Son

How do we know what we know? It depends on the time and place. In the medieval times (generally cited as the years between the 5th and late 15th century), people had their own distinct beliefs about medicine, history, and magic. What passed for medieval “common sense” might not pass today’s standards for proof, or, um, medical sanitation. From bright ideas about the occult and Bibles co-produced by Satan, to household cures involving hot pokers and animal enemas, the beliefs of the medieval public reflected the gritty times in which people lived (and perished). Prepare for one wild ride into the past with these 42 unsettling facts about medieval beliefs.

1. Sensual Care

In the 16th century, mercury was a common treatment for syphilis and other sexually transmitted diseases. Just apply directly to the nose or mouth or, if you’re feeling trendy, do the “fumigation” method and simply vaporize the substance in a neat, air-freshening steam. Side effects include loose teeth and ulcers of the gum. Rather unsexy.

2. Man-Made Miracles

Cannibalism wasn’t always a taboo. Medieval doctors kept their patients in check with drinkabe byproducts of human blood and flesh. “Mummy powder” was a commonplace fixture of 12th century apothecaries, and these practices even had a name: "body medicine". Well into the 17th century, even English kings like Charles II dined to a healthy regime of what he called “King’s Drops,” aka booze mixed with crushed human skulls. Salty!

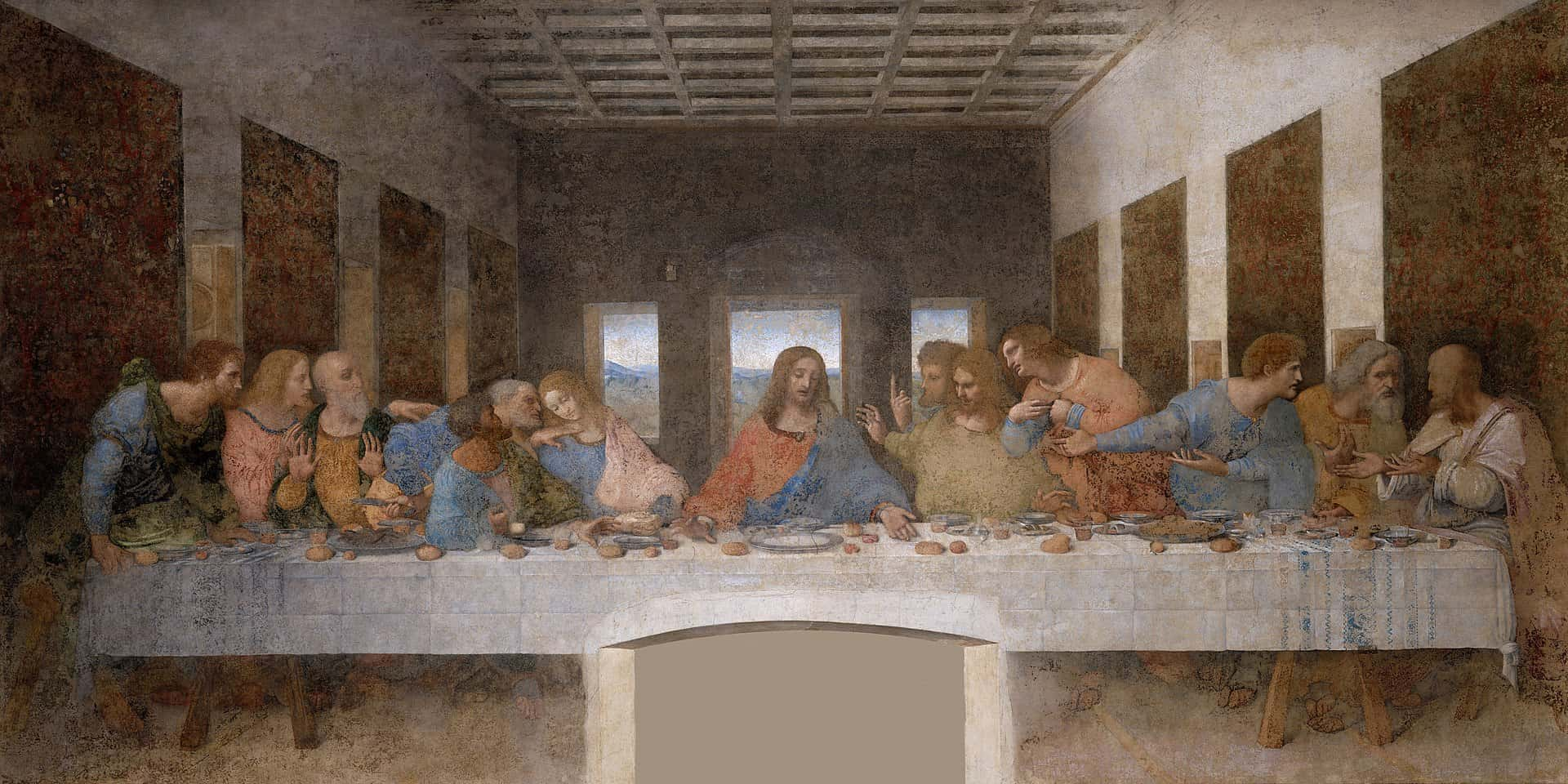

3. Bad Math

Superstitious bias towards the number “13” really took off in the medieval period. Aversion to the number arose from the fact that there were 13 apostles (including Jesus) at the Last Supper. Even in the 16th century, having 13 people together could signal you were a witch. Good thing I don't have that many friends.

4. The Big Sneeze

Blame the medieval times for why you sometimes say, “Bless you!” when someone sneezes. The general assumption has been the “blesser” was sending their good will to the sneezer, whose soul had just been ejected from the body via nasal expulsion. Other people note this practice emerged in the time of the Plague—when your last sneeze might well be your last ever, so get those blessings in now!

5. Little Miss Lace & Grace

Medieval Germans viewed clothing made by young girls as very lucky. Specifically, a shirt spun by a girl under seven years of age would bring good luck, and a shirt spun by a girl aged five to seven would even protect the wearer from magic. Likewise, wearing a shirt made from thread spun by a five-year-old girl to court would bring a just verdict. Frankly, this just sounds like cute ways to justify child labor.

6. The Stars Say to Drop That Scalpel

Doctors of the European 1500s were legally required to check a patient’s horoscope before performing any direct medical treatment. Imagine getting your surgery delayed because you’re a Rising Taurus and Mercury is in retrograde.

7. Bleeding Awesome

Bloodletting was an important part of any doctor’s belief system. A patient had two options: leeches or venesection. With the leeches, a “blood worm” would be administered on the pertinent body part and the creature would—in theory—suck the illness out. It sounds a little nicer than the latter option: the doctor would just slice open a vein with his “fleam” and hope for the best.

8. Opposites Are Magic

The Middle Ages observed “magnetism” as a quality of the occult. Well, magnets are pretty cool.

9. Dying to Practice

Oftentimes, medieval practitioners of “necromancy”—the occult art of summoning the spirts of the gone—were members of the Christian clergy. In fact, Christian rites were sometimes intermingled with more overly occult practices.

Sign up to our newsletter.

History’s most fascinating stories and darkest secrets, delivered to your inbox daily. Making distraction rewarding since 2017.

10. No Magic Allowed

In 1456, Johannes Hartlieb put down seven “arts” to be officially forbidden in canon law. These arts were: nigromancy (traditional “dark arts”), geomancy (divination around the earth and dirt), hydromancy (water-based scrying), aeromancy (tossing sand or seeds in the air to read how it settles), pyromancy (reading fire signs), chiromancy (palm-reading), and scapulimancy (reading animal bones).

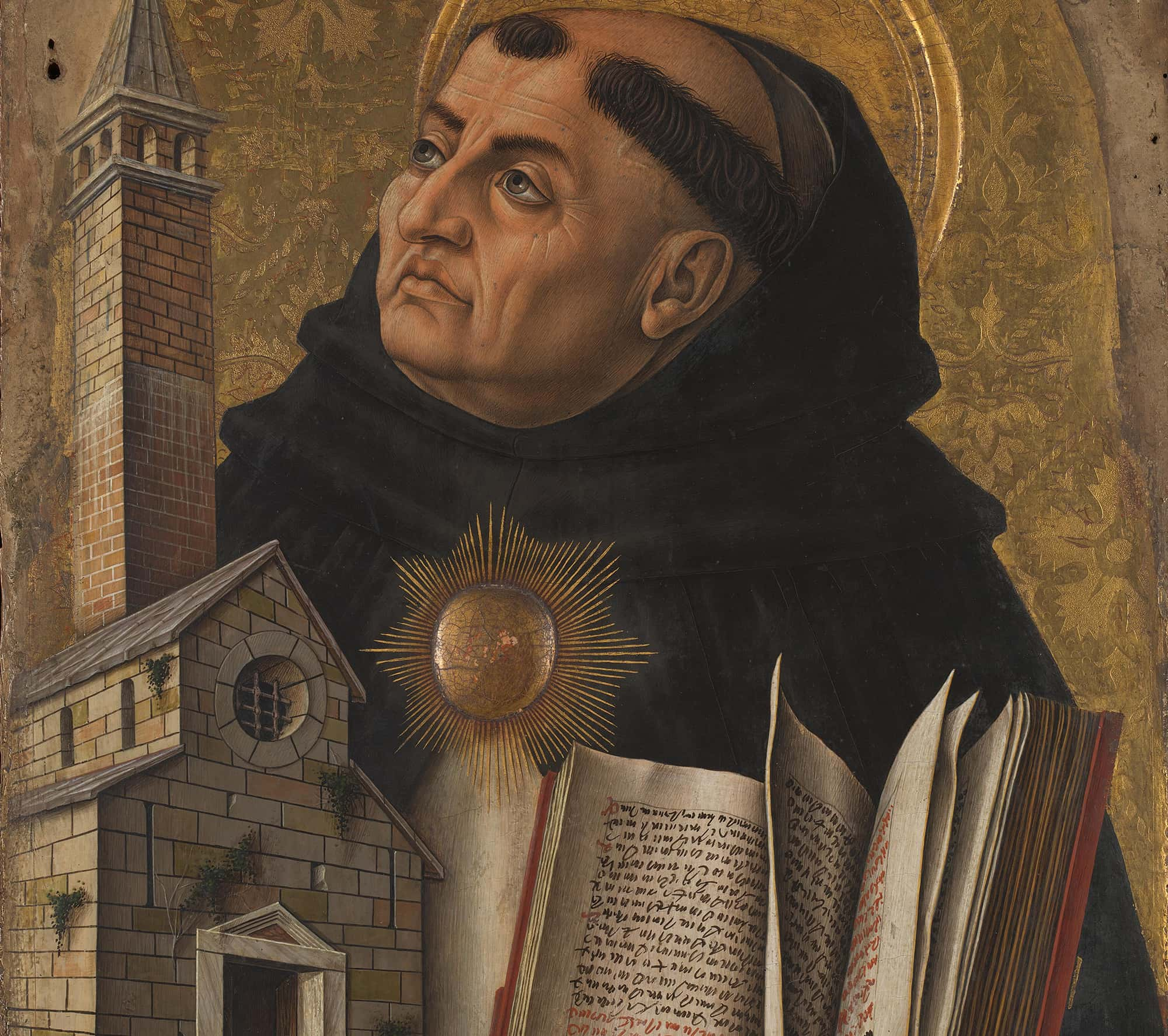

11. Hard Rock Philosophy

The philosopher’s stone is a central part of medieval mystic mythology. It was a rock believed to be invested with alchemical powers, even offering its user immortality. If you asked medieval legend, the 13th century intellectual Albertus Magnus passed the infamous stone down to this pupil—the even more famous Thomas Aquinas.

12. 5 Reasons Why Not

Famed medieval scholar Albertus Magnus ranked five intimate positions from most to least “morally” acceptable. Since this is a family website, we won’t list them here. But it will surprise few of you that the least offensive position was, from the top, “missionary".

13. Just Sometimes a Sin

In some periods of the Middle Ages, intimate work was not only believed to be acceptable, but it was also marginally encouraged by the Church as a way to curb uncontrolled lusts. Even St. Thomas Aquinas once wrote, “If prostitution were to be suppressed, careless lusts would overthrow society".

14. Ladies First

In the 13th century, a female orgasm was considered a necessary part of human conception. Granted, that was mostly because they thought female anatomy was just like a man's, only inverted, but you can't win 'em all.

15. Women’s Time to Shine

At least officially, the majority of medieval “magic” practitioners were men. “Female” constructions around ideas of medieval magic, and the subsequent persecution of “witches,” are more common to the early modern age than the middle ages. You can thank Heinrich Kramer’s warnings in his 1487 Hammer of Witches for that feminine connection.

16. From Mark to Conspirator

Before the 15th and 16th centuries, medievalists perceived female devil worshippers as simply “foolish,” you know, in that female way; they were “duped” by dark forces rather than inherently evil themselves. As with many medieval views about women and magic, that changed in the early modern period. Soon women were drawn as happy to make contracts with the devil. At least they have more agency?

17. Beast for Fashion

Your animal fashion statement could double as a handy token to ward off the ills of medieval living. Some people used seal skin to charm lightning away; others used vulture remains as protective jewelry. Staying safe in the Middle Ages had never been so boho-chic.

18. Green in Every Way

It was not an uncommon practice for gardeners to enlist virgins to plant their olive trees. Their “pure” status was “scientifically” proven to stimulate growth.

19. Bandages & Bedtime Tales

There’s power in storytelling. One medical treatise from this era recommends that you can staunch blood by applying olive-oil-soaked wool as you tell aloud the story of Longinus, a man who was cured of blindness by Christ’s blood. In fact, many medical treatments revolve around a mix of physical application and sympathetic tale-telling.

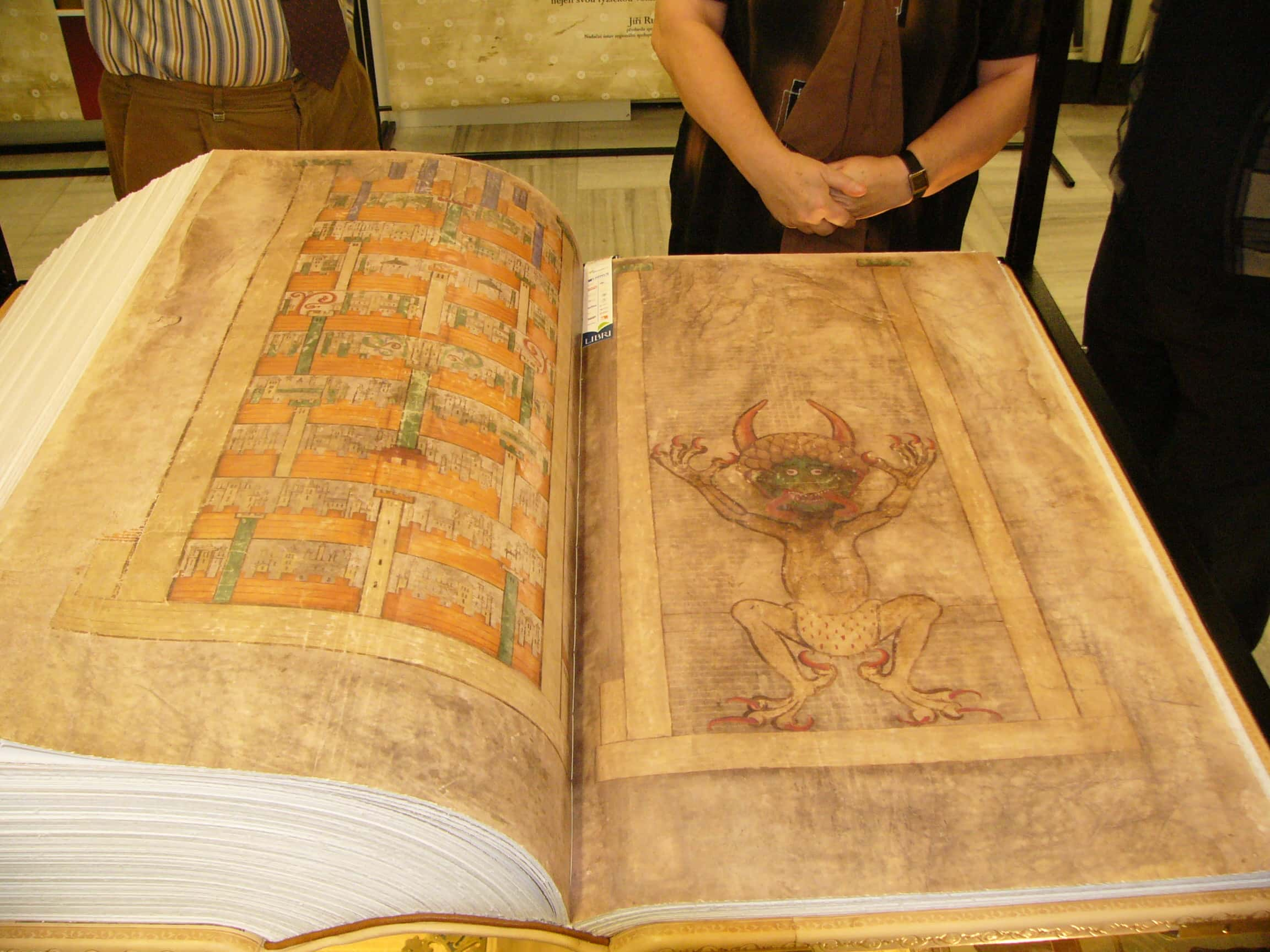

20. Co-Authorship From Inferno

“The Devil’s Bible” is a legendary Latin manuscript that’s said to be the product of a monk’s bargain with Satan himself. In the 13th century, a monk was about to be executed for his offences unless he could compose a single, impressive work in one night. To achieve this impossible task, the monk sold his soul to Satan and produced this 165-pound, three feet long book. While that’s just a legend, The Devil’s Bible does exist as a real text, and it appears to have been written completely by the hand of a single scribe…

21. The Can’t Be Burned Burn Book

It’s said the Vatican’s secret archives still contain original editions of The Grand Grimoire, a black magic text book that dates back as far as 1421 (though it likely was written in the 19th century). It’s also said that this book is indestructible and impervious even to immolation.

22. It’s Probably Just Doodles

The 15th century Voynich Manuscript is infamous because scholars just can’t agree on what it’s about, or even what language it’s written in. Composed with images of uncovered ladies, obscure zodiac symbols, and indecipherable herbal recipes, the book inspires no shortage of controversy. Whatever medieval belief system it’s supposed to have upheld, we're betting it was wicked.

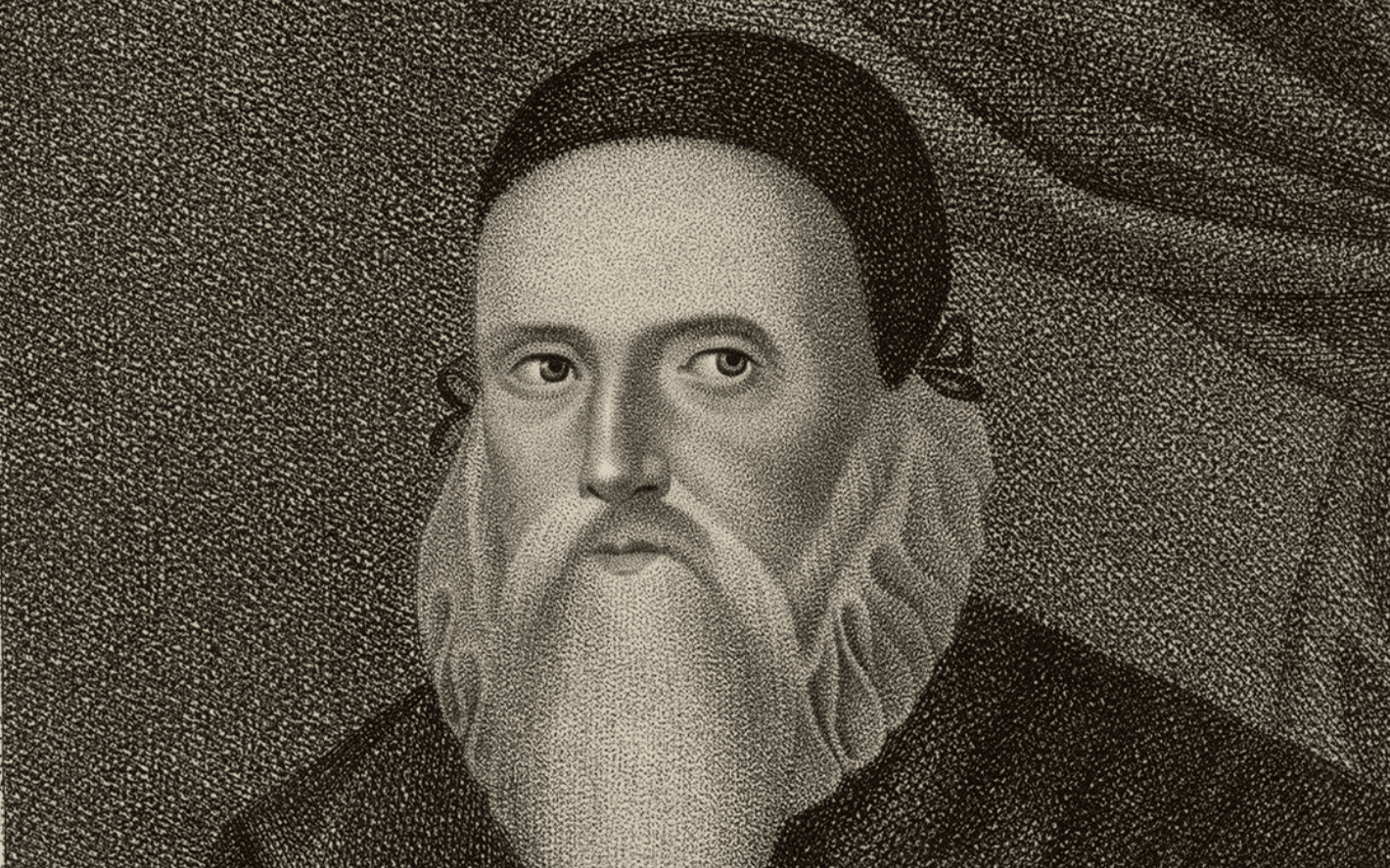

23. Angels in the Far Out There Field

When John Dee wasn’t busy advising Queen Elizabeth I, the famed mathematician was trying to contact angels. Dee spent most of his life trying to decipher the strange codex of magic called Aldaraia (sometimes called the Book of Soyga or, less nicely, “the book that kills”) with the hopes that the jumble of magic codes, genealogies, and incantations would aid him in crafting the ultimate fan mail to the Heavens. As far as we know, Dee did not complete this lofty task.

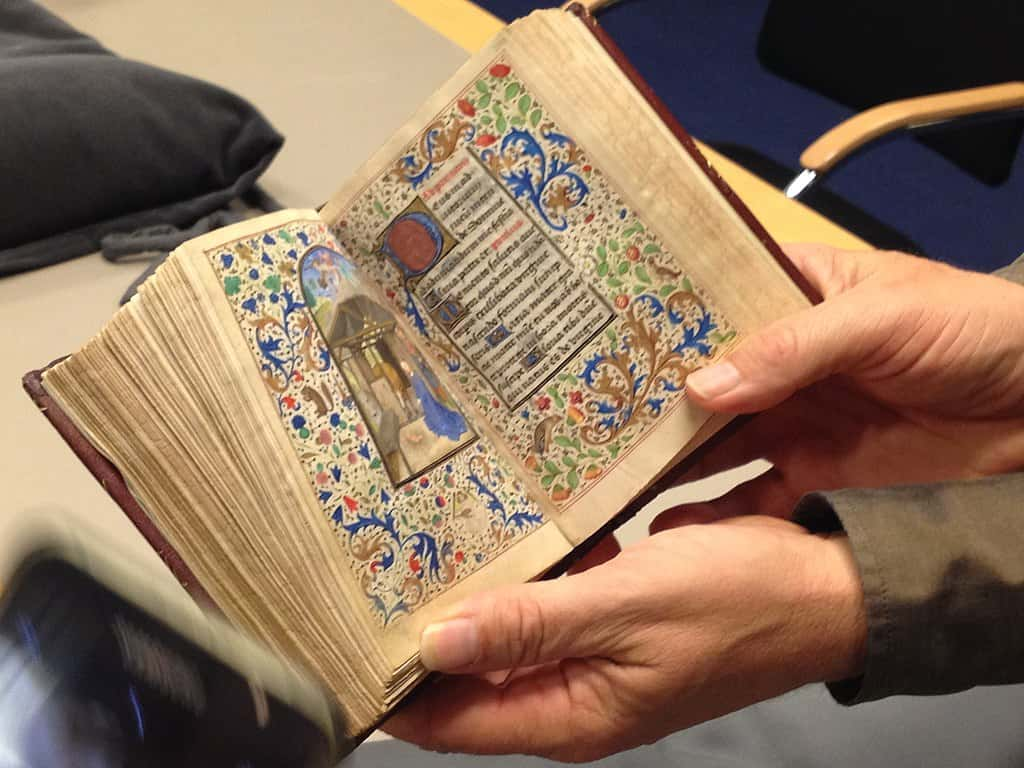

24. Dark Magic 101

One of the most famous dark magic textbooks of the pre-modern ages is the neatly-named The Necromancer’s Manual. Written in 15th century Latin, it is completely about the dark, “evil” magics that contemporaries were told to avoid. It also divides its powers into three sections: illusionist magic (tricks to the human sense), psychological magic (tricks to the human sense of persuasion), and finally divinatory magic (the heavy stuff that lets you see past and future). Finally, a coherent academic index.

25. No Assembly Required

People in the past put a lot of faith in sperm. More specifically, they believed that every male sperm “sample” already had a fully-formed-and-ready-to-grow person inside. It was simply the woman’s job to be the passive incubator for the seed of her male partner, who was the true source of human life. Not sure we’ve gotten over that…

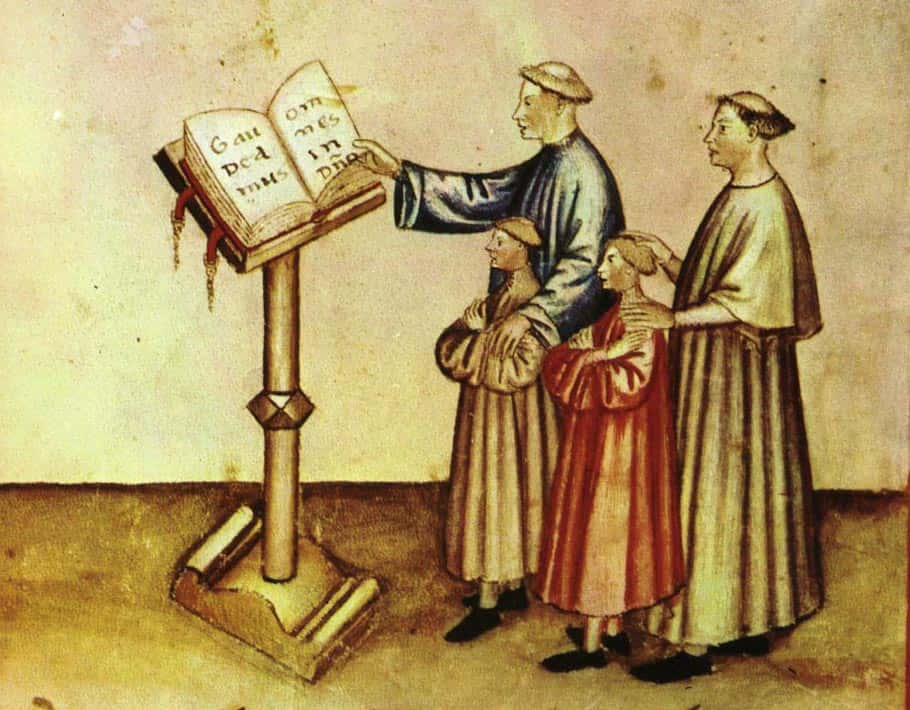

26. The Devil Is in the Details

Don’t blame me for my typos! The devil did it! Or rather, the devil’s special friend, Titivillus. Back when “printing machines” usually meant “a room of monks trying their best,” mistakes were a common part of book reproduction. To explain away these typos, monks made up the charming character of Titivillus, the “patron demon of scribes,” who was the real culprit in poorly proofed work. Alternatively, Titivillus would also collect every monk’s mistakes into his handy sack and present these errors as testimony against the monk’s entry to Heaven. I’ve never been more grateful for Spellcheck.

27. In the Nowhere of Middle

Before GoogleMaps, many kingdoms believed in the existence of a giant mythical land mass, which laid in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. This extra continent alternatively went by the names of “Pacifida,” “Lemuria,” and the simply-put “Mu".

28. Mrs. Malaise 1493

Unable to wrap their heads around abstract concepts like “communal infection” and “virulent disease,” the common people of Europe often embodied the Plague as “The Pest Maiden". Sometimes, she emerged in Scandinavian countries as a young lady, surrounded by Blue Flames and ejecting herself from the mouths of the gone. Other times, she was an older woman with a broom and was accompanied by a man with a shovel. The man was sometimes merciful, but—of course—the older woman was a shrewish type who let no one survive.

29. Vile Veggies

Western countries in the medieval ages thought there was something inherently bad about Brussel sprouts. Spiritually, not culinarily. In fact, foodies of Great Britain thought they were outright cursed. So, they cut them in cross shapes. I’d also wash them since this is the medieval times, but hey, different folks, different cross-shaped strokes.

30.Dust Bunnies

Who needs the birds and the bees? People of the Middle Ages believed that worms, insects, and mice could spontaneously manifest from trash and dirt.

31. Born Numb

Scary to think that “Babies feel pain” is a very recent belief. In the past, people thought babies were simply too underdeveloped to sense physical distress. Thus, surgeries were performed on infants without anesthesia, and any crying was the result of ill-mannered childishness, as opposed to any external forces.

32. Sin to Sing

It’s an exaggeration that the medieval churches of Europe outright criminalized a certain combination of notes as too “devilish” to play. Church music was simply too diverse to accommodate such a ban. More likely, monks discouraged composers from using “the Devil’s interval,” or the tritone, in their godly music.

33. Ballistic Remedies

Cheat on your diet with beaver testicles. In medieval times, beavers were classified as a breed of fish. As a result, consumption of beaver did not count as “eating meat” during a religious fast. Moreover, their furry private bits were very valuable in medicine recipes, a belief that gave birth to the myth that a beaver would bite its own testicles off and throw it at human hunters to escape with its own life.

34. Poke and Pray

In the Middle Ages, the divine rights of kings were taken as a given. So too was their divine and healing touch. For half a millennium, people believed their monarch had the power to cure disease with their noble hand. “Scrofula”—a disease resulting from tubercular, inflamed lymph glands in the neck—was something you should especially see the king about. The 11th century King Edward the Confessor is generally credited as the first monarch to perform the ritual of offering his healing touch to the commoners.

35. From Under the Sea and Into Your Heart

Move over, Ariel. In this house, we stand for the uncovered , godless “merman” of Orford. An abbot by the name of Ralph Coggeshall claimed that, in 1161, a group of fisherman captured a hairy, bald, bearded “merman". Naturally, they chained him up and tortured him because he did not speak and knew nothing of their Christian God. When the mob gained some chill, they let their guest out for some exercise in the sea, at which point he broke through the nets and escaped with a miraculous agility.

36. Casper the Bloodthirsty Ghost

People of medieval Britain lived in a healthy fear of spectral phantom huntsmen, who would fling themselves into their homes at night in their eternal hunt for souls. In Germanic lands, the ringleader was sometimes identified as the mythic Odin. If you heard clanging bells at night, your best bet was to lay low on the ground and hope they didn’t swoop you up.

37. You’re Not the Father!

Just giving birth to a kid was hard enough medieval Britain. The public certainly didn’t need more fears of kidnapping fairies injected into its popular imagination. But alas, it was believed that nymphs could, would, and did take healthy children away from parents and replace them with usually sicker, doomed replacement kids called “changelings". Today, it’s generally accepted that this was the collective wishful thinking of parents of diseased, disabled, or gone children who hoped that somewhere out there, their real child was alive and healthy.

38. Buffy the Medieval Vampire Slayer

Although the sophisticated vampires of our popular imagination come from 19th century horror literature, these fanged beasts have progenitors from as early as the 11th century. Medieval vampires were usually thought to be real corpses raised back from the gone. One story tells of a person who perished grief, but whose neighbors insisted he was still hanging around and spreading illness. Naturally, the village opened his grave, and impaled him with a stake just to be sure.

39. Wagging Tails

It was a common belief that witches kept male genitalia as house pets, even going as far as to feed them and house them in nests. Puts a new spin on My Pet Rock, right?

40. Boar You to Demise

Nothing gets earthier than a boar bile enema. Administered by “clysters”—large, long, metal tubes with cups—they can’t have been a comfortable way to pump medicine in medieval subjects. But where they truly that awful? Louis XIV “The Sun King” of France had as many as 2,000 of these during his lifetime.

41. Golden Cure

Urine was believed to be a great antiseptic. It was certainly good enough for Henry VIII’s surgeon, who abided by a policy that all battle wounds should be rinsed with the stuff. What’s more twisted? It wasn’t a terrible idea when you consider the alternatives; clean water was hard to come by in the Medieval Ages. Might as well use what you got.

42. Give ‘Em the Hokey-Pokey

Got hemorrhoids? A medieval monk would tell you to take a hot poker to the sore spots and ease those woes. This was standard until the 12th century, when a Jewish doctor by the name of Moses Maimonides challenged this medical hot take. Instead, he suggested that a good bath would do the (less painful) trick.

Sources: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22