"How delightful are the pleasures of the imagination! In those delectable moments, the whole world is ours; not a single creature resists us, we devastate the world, we repopulate it with new objects which, in turn, we immolate. The means to every crime is ours, and we employ them all, we multiply the horror a hundredfold."

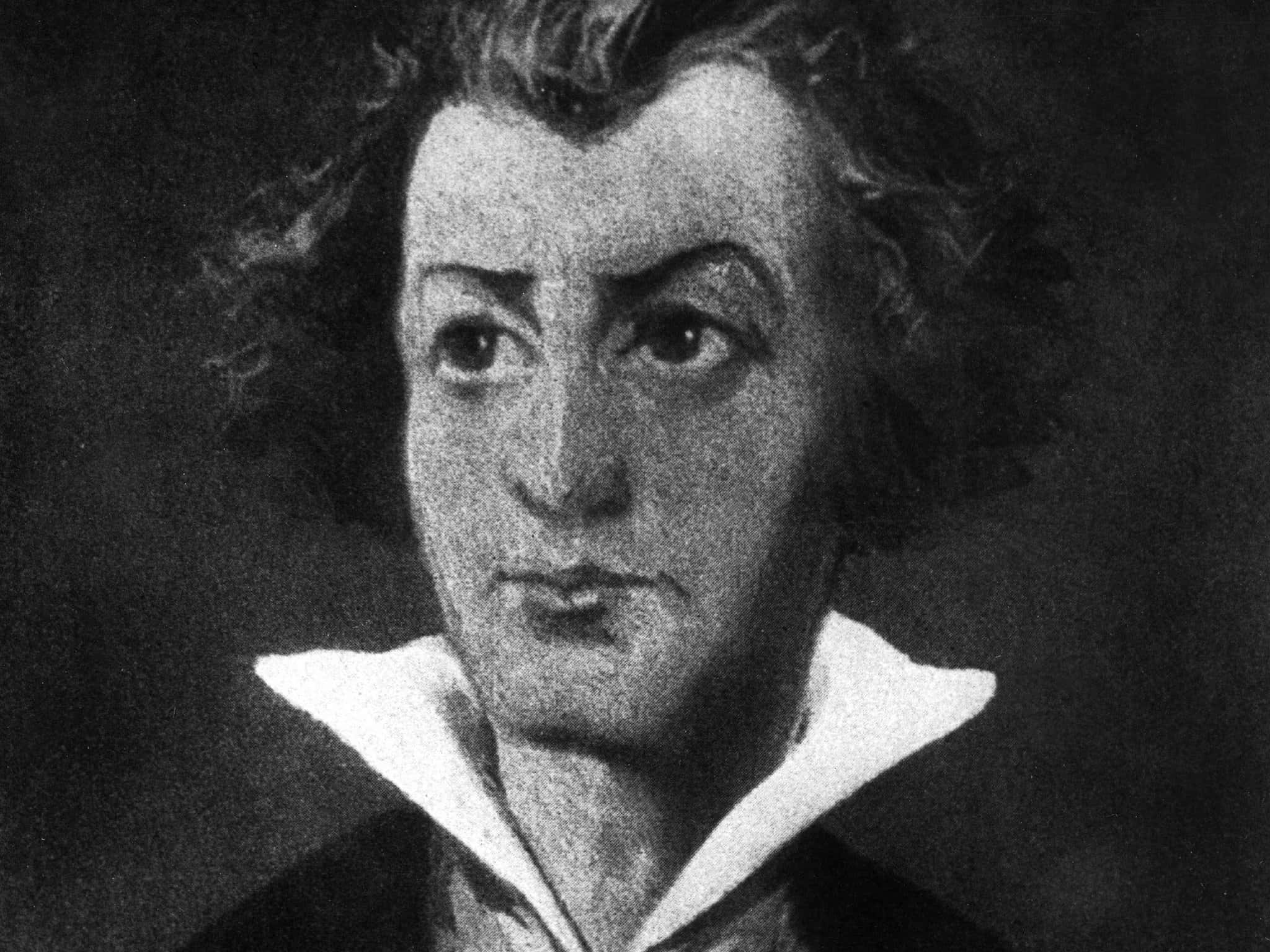

“In order to know virtue, we must first acquaint ourselves with vice.” —Donatien Alphonse François, the Marquis de Sade

The Marquis de Sade was once synonymous with rakes, libertines, and all manner of promiscuity, and he lives on today in the word "sadism." Nonetheless, this French nobleman was also a cutting critic of society, and he loved to throw his convictions in the face of proper culture, whether through his novels, short stories, and plays, or his personal relationships and letters. Who knows if we would even have gotten Fifty Shades of Grey without him? The things he wrote, said, and even did would make your mother blush while clutching her pearls in disbelief, but there's so much more to this 18th century revolutionary who was way ahead of his time.

Marquis De Sade Facts

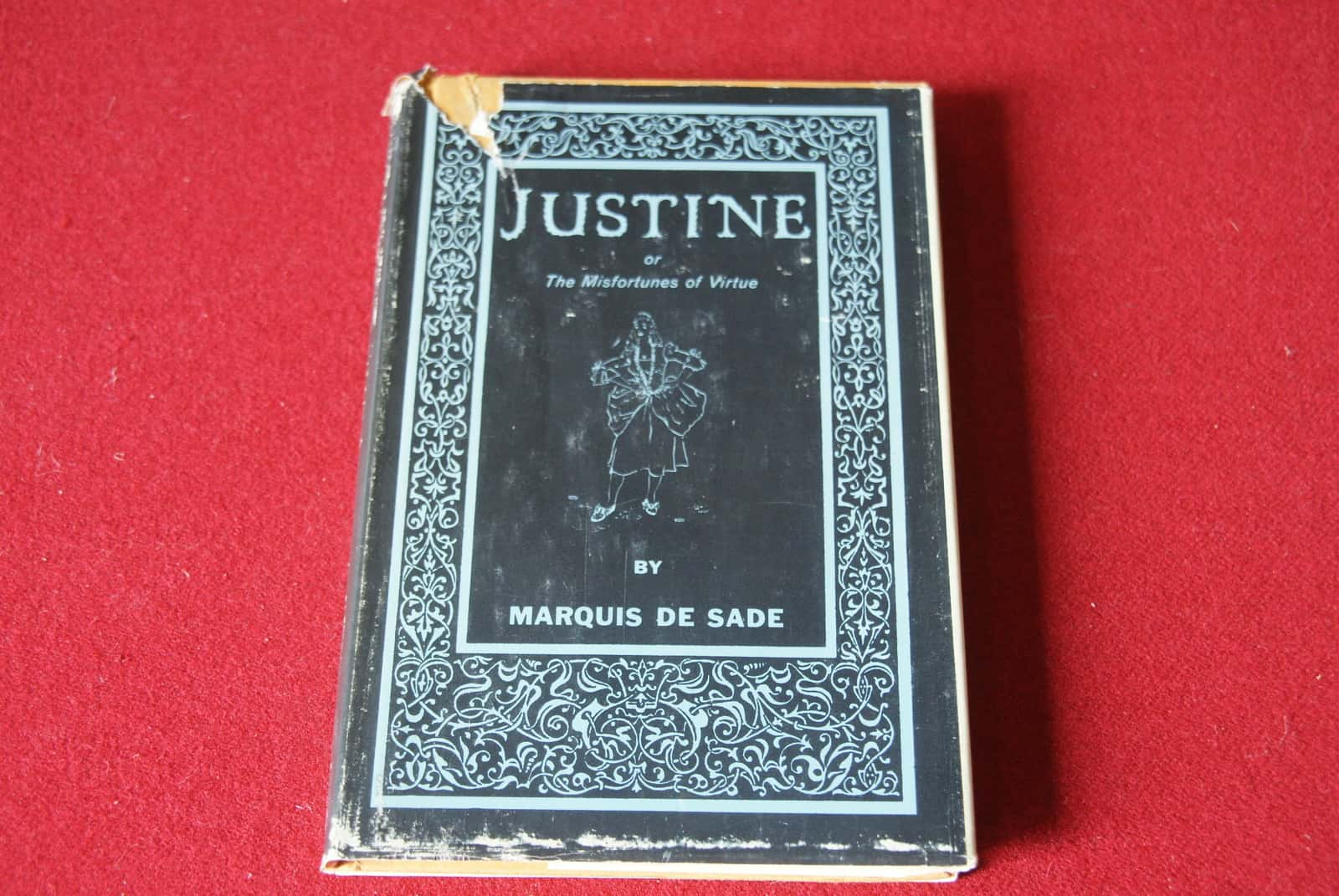

42. Just Call Me Marquis

He was born Donatien Alphonse François in Paris, France on June 2, 1740, but everyone knew him as the Marquis de Sade. De Sade gained fame (and a heaping spoonful of notoriety) through sexually explicit works like The 120 Days of Sodom, The Crimes of Love, and Justine.

41. High-Minded

Though de Sade was ruinously infamous in his day, many brilliant French intellectuals have published studies on him, from Michel Foucault to Roland Barthes.

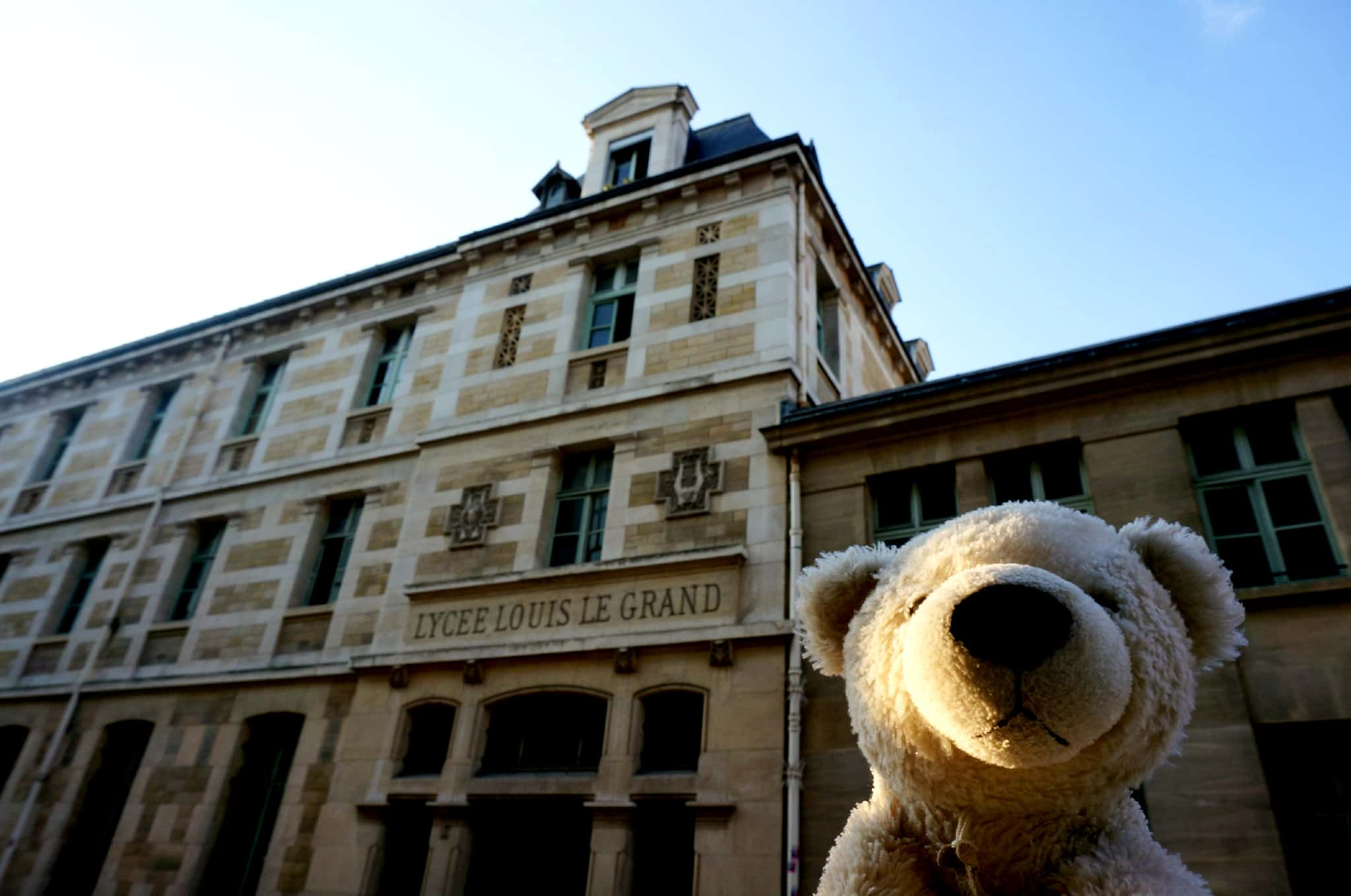

40. Rebel Rebel

De Sade had a foul temper, and was so rebellious as a child that he once beat the French prince. As punishment, he was sent to spend time with his uncle, a church abbot, in the south of France. But four years later, he returned to Paris and became a student at the Lycée Louis-le-Grand.

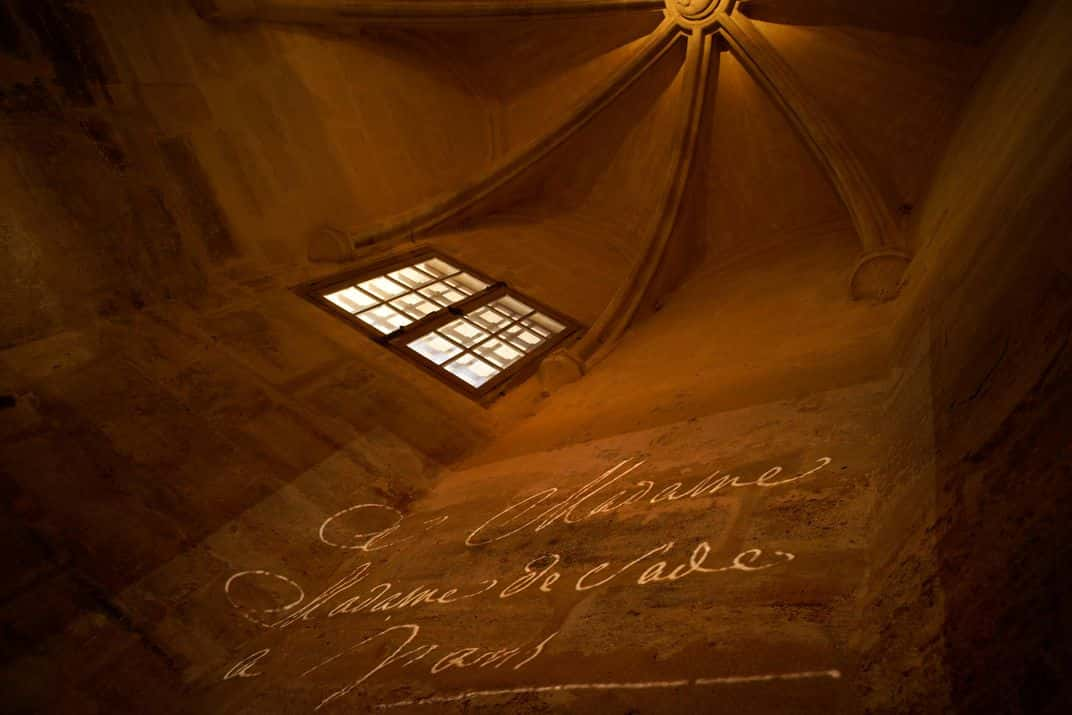

39. Prison Inspired Him

De Sade spent a lot of time behind bars. In fact, 32 years of his life were wasted going back and forth between prisons and asylums, but it was while he was imprisoned in Bastille that he wrote The 120 Days of Sodom. Much of his controversial work was done while he was incarcerated.

38. Controversial Revolutionary

Many historians and anthropologists have studied de Sade’s work. Some even consider his work to be the precursor of psychoanalysis, a concept that came to the cultural forefront through Sigmund Freud. De Sade’s philosophy was also heavily linked to nihilism, as he denounced Christian values and morality.

37. Not That Evil

According to Francine du Plessix Gray, the Marquis' biographer, de Sade wasn’t actually into violent activities in his non-sexual life, and even sexually, he liked to take as much as he gave, if you know what I mean. Even more telling, although the activities were quite common for the noble set, he never fought in a duel and didn't take an interest in hunting.

36. Openly Libertine

Back in the day, being a sexual libertine wasn’t that much of an oddity. Sexual debauchery was somewhat de rigueur in aristocratic ancien regime circles, and even de Sade’s uncle was known for his sexual shenanigans. It's just that the Marquis was particularly perverse and particularly open about his proclivities.

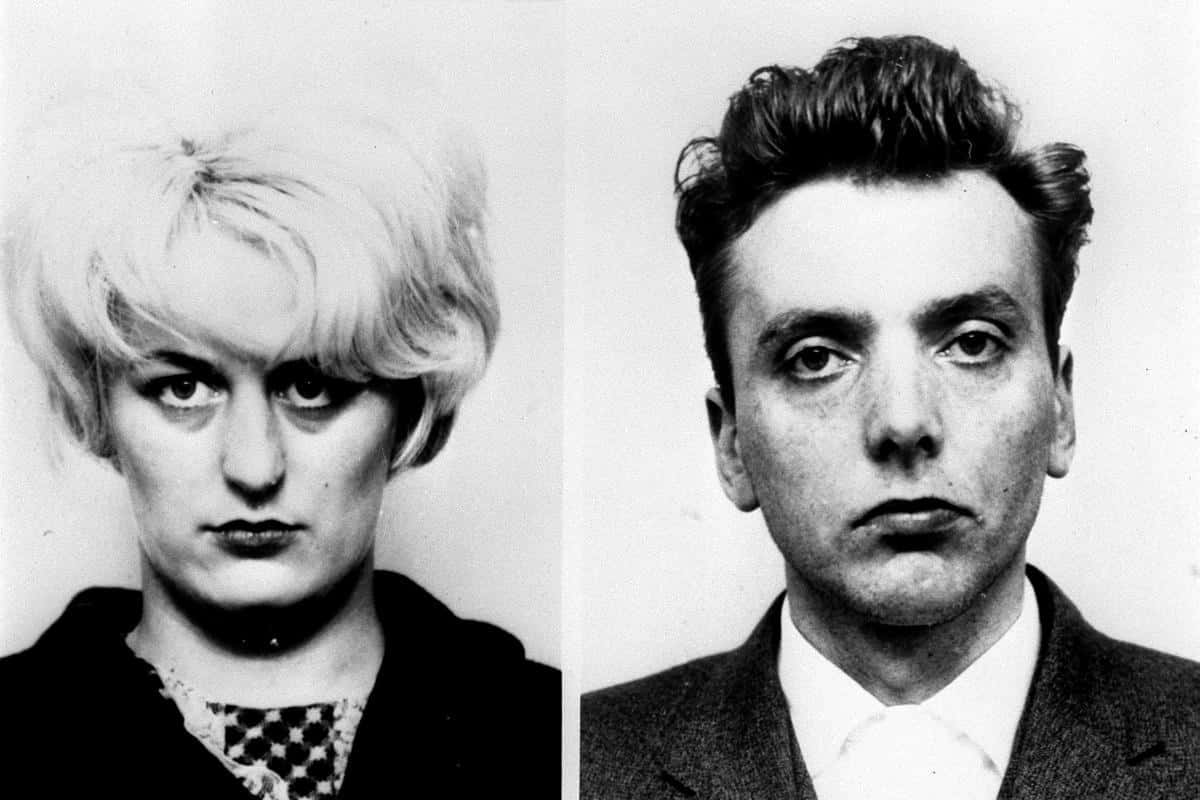

35. Don’t Call Me Sade

Ian Brady and Myra Hindley were the couple behind the infamous Moors Murders in Britain in the 1960s; they killed five children and stunned the United Kingdom. It is said that the couple loved attending the library, where the works of the Marquis de Sade were among their favorites.

34. Finding Inspiration

De Sade’s bizarre and aggressive work has inspired many characters and figures throughout film, and he's also had his share of real-life fans. French novelist Gustave Flaubert and critic Camille Paglia both cite de Sade as an influential figure in their work. As for movies, American Psycho is (perhaps unsurprisingly) packed with references to Sade.

History's most fascinating stories and darkest secrets, delivered to your inbox daily.

33. Celebrating Sade

Despite the controversial nature of his work, de Sade has been celebrated as a cultural figure by the Musée D’Orsay, which held an exhibition about his influence over the works of Francisco Goya, Pablo Picasso, and French painter Théodore Géricault.

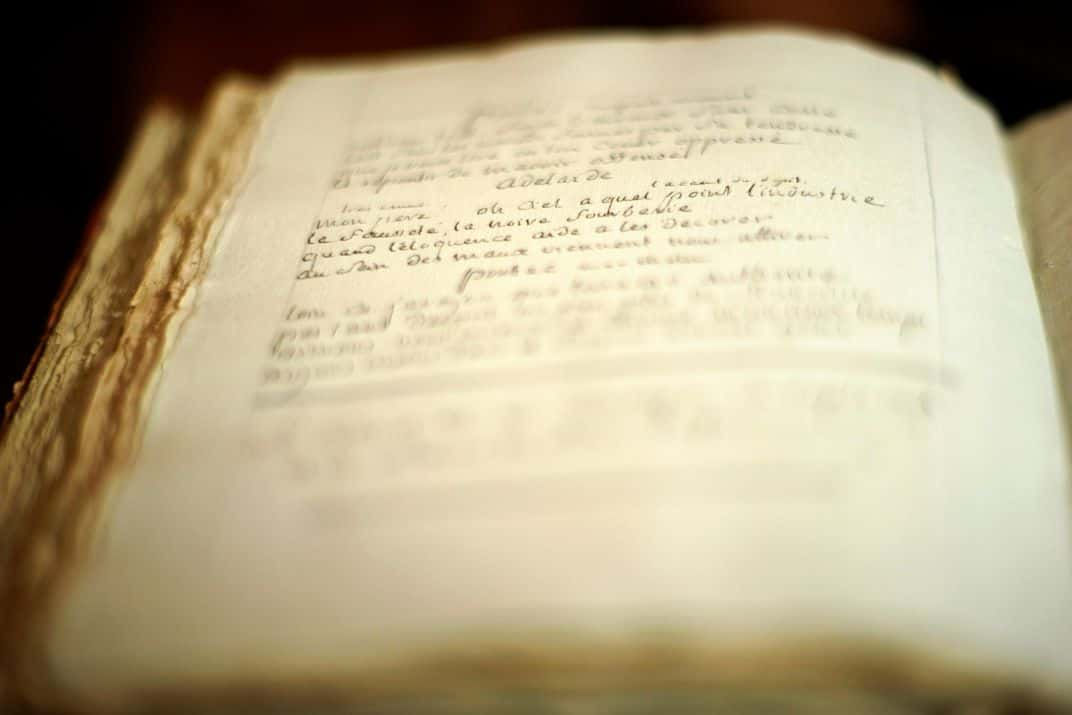

32. 12-Meters Of Fun

De Sade's controversial novel The 120 Days Of Sodom was written on a small 12-meter-long parchment strip over a period of 37 days. He was imprisoned in the Bastille at the time of its creation, so it’s safe to say he had a lot of time to focus on his writing.

31. Divisive Figure

Many artists and writers that followed are confused by and divided on de Sade’s work. Some claim he’s a literary visionary who wasn’t afraid to explore the human depths of sexuality, even deeming him a feminist. Others, however, have been less than kind to his legacy.

Youtube

Youtube

30. Taking Charge

When de Sade went searching for potential mates, he often visited brothels. According to legend, during one visit the women were already waiting for clients, so de Sade proceeded to direct the, er, proceedings.

29. Life Is Like a Box of Chocolates

On one of his brothel visits, de Sade reportedly brought a crystal box filled with chocolates to give to his companions. After some time, however, many women reported feeling violently ill, started vomiting a dark substance, and were eventually brought to police headquarters. In their deposition, the women accused de Sade of poisoning them with the confections. As it turns out, de Sade wasn't trying to kill anyone; he had merely made the chocolates with a mixture of aniseed and cantharides, which were commonly used as an aphrodisiac at the time.

My drivewithpride

My drivewithpride

28. Scouring the Streets

De Sade often tasked his servant, Latour, with roaming the streets and procuring mates for him. The Marquis de Sade’s type? ''Very young.''

27. Pro-Feminist Hero?

Despite de Sade's ignominious deeds, some critics argue that his novels are proto-feminist, as they often show women in dominant rather than submissive sexual positions. Curator and biographer Annie Le Brun has said that “His novel Juliette is one of Europe’s first pro-women books, where women dominate entirely."

26. Commitment Issues

For all his vices, de Sade was a family man. He married Renée-Pélagie de Montreuil, a wealthy young woman. The marriage stabilized his financial situation, but it didn't stop him from having affairs with other women in order to satiate his thirsts. He would often rent out rooms away from home to fulfill his fantasies.

25. Money Talks

De Sade would have likely jumped with glee if he knew that his handwritten scroll for The 120 Days of Sodom was purchased for approximately $7.8 million in 2014.

24. When Donny Met Marie

At one point, Sade met Marie-Constance Quesnet, who already had a child named Charles. The three lived together, but de Sade claimed there wasn't anything physical going on between himself and Quesent. Quesnet was the breadwinner while De Sade served as a father figure to her child, and she remained with him until his death.

Pinterest

Pinterest

23. Corporal Punishment

As a child, De Sade faced corporal punishment for misbehaving at school. He was only about 10, but this opened the door to him learning about flagellation for pleasure, and after this point it became one of his many obsessions.

22. Dying Wish

Sade wrote in his will that no one was permitted to open his body for any reason, and that his remains should not be touched for 48 hours. He also asked that he be placed in a coffin and buried in Malmaison, on his property. His final wishes were not to be: Charenton asylum became his burial place, and his body was later unearthed and his skull removed for study.

Colchester Road Baptist Church

Colchester Road Baptist Church

21. Banish the Thought

De Sade's descendants were ashamed of the legacy he left behind, and even refused to be associated with the name de Sade for five generations, until Count Hugues de Sade realized that capitalizing on the family name would bring him profit.

20. Three's the Charm

Despite his incessant cheating, divorce in those days wasn't as easy as it is today. So, de Sade and his wife actually ended up having three children together, and she stuck with him for a good many years and through many scandals and embarrassments. She did, however, manage to divorce him in 1790.

19. The Revolution Favored Him

De Sade had written a handful of manuscripts while in jail, but creative productivity is cold comfort while you're sitting in a cell. After the French Revolution, de Sade convinced the new regime to release him, rebranding himself as "Citizen Sade." (No, really.) But then Napoleon Bonaparte showed up and locked de Sade up again, which was a total bust for the prince of perversion.

Youtube

Youtube

18. Good Guy Sade

During his bid as Citizen Sade, he became president of the Pike Section of Paris. While in the position, he pushed to have hospital patients get their own bed in order and do away with sharing, which was a common practice in those days and increased the risk of illnesses.

17. Give Him My Blessing

A lot of de Sade's work seems blasphemous, but ironically, Francois Simonet de Coulmier, a Catholic priest and the director of the asylum where de Sade was eventually locked away, encouraged the Marquis' writing. He gave de Sade writing materials and allowed Marie-Constance Quesnet to live in the room next to him. Under Abbe de Coulmier's supervision, de Sade also directed a play using other patients as actors.

16. Not a Fan of Death

De Sade opposed the death penalty, and given that he spent so much time behind bars, who could blame him? As he once said, "The law which attempts a man's life is impractical, unjust, inadmissible." Oddly enough, though, he had no issue with murder.

15. Victoria's Secret Sade Lingerie

Hugues de Sade is a direct descendant of the Marquis, and he created a line named Maison de Sade, selling things like scented candles and wine. In 2015, Hugues, referring to his ancestor, told Smithsonian Magazine that: "He adored fine wine, chocolate, quail, pâté, all the delicacies of Provence.” Hugues also said at the time that he planned on creating a Victoria's Secret Sade lingerie line. Bet you those bras are even more uncomfortable than usual.

14. Soldier On

De Sade joined the elite military academy at 14. He moved up in the ranks, and eventually went from sub-lieutenant to Colonel of a Dragoon regiment. He even fought in the Seven Years' War.

13. Both Ways

There's a reason de Sade's life was deemed scandalous. He not only slept with his wife's sister, Anne-Prospere, but also with his own employees, both men and women.

Redbubble

Redbubble

12. One for the History Books

Sexual Sadism Disorder is a psychological condition that takes its name from de Sade, and is characterized by experiencing arousal from inflicting extreme, non-consensual pain or suffering.

Emotional intelligence Project

Emotional intelligence Project

11. Boys on Film

De Sade's relationship with Abbe Francois Simonet de Coulmier and his stay at the Charenton insane asylum has been documented in the film Quills, which starts Geoffrey Rush as the Marquis and Joaquin Phoenix as the Abbe.

10. Murder in the Chateau

De Sade's various vices had to catch up with him some time, and it wasn't always in prison or asylum stints. For a while, de Sade's life was marked by a vicious cycle: he would mistreat his employees, they would then accuse him of assault and abuse, and the Marquis would often react by fleeing the country. In 1777, after yet another set of girls fled his chateau, the father of one of the women marched up to de Sade and attempted to shoot him at point-blank range. Lucky for the Marquis, the gun misfired.

9. To Catch a Predator

In late 1777, Sade went to visit his mother, who he had been told was very ill. However, it was a trick: Authorities were trying to lure him back home. The worst of all this? Is mother actually had died just before these events. De Sade was caught and thrown in prison, but he appealed in 1778 and narrowly avoided the death sentence. Then he ran away in typical Marquis de Sade fashion, but was quickly apprehended.

8. Back to the Looney Bin

De Sade was often too much for even prisons to handle. After being thrown out of Sainte-Pélagie Prison for disturbing and seducing the prisoners, he was thrown into the infamous Bicêtre Asylum, which was really just another prison. Fortunately, his family intervened and Sade was transferred to the gentler Charenton Asylum in 1803.

7. Minor Problem

While at the Charenton Asylum, Sade met Madeleine LeClerc, the child of an employee who worked at the asylum. The girl was only 14 years old when de Sade began engaging in adult activities with her. The two continued their affair until 1814, when Sade died; their relationship lasted for four years.

Pinterest

Pinterest

6. Final Days

Though he had Madeleine to keep him company, at the time of his death de Sade was broke, suffering from obesity, and a social pariah. On top of that, at the end of his life, de Sade had spent most of his adult life incarcerated in one form or another.

5. Behind Bars

In an infamous incident in 1768 on Easter Sunday, de Sade lured Rose Keller, a German immigrant, to his room under false pretences, where, according to Keller herself, he tied her to a bed and assaulted her. She escaped through a window, and though his family paid her off, de Sade was arrested once she told her tale to police.

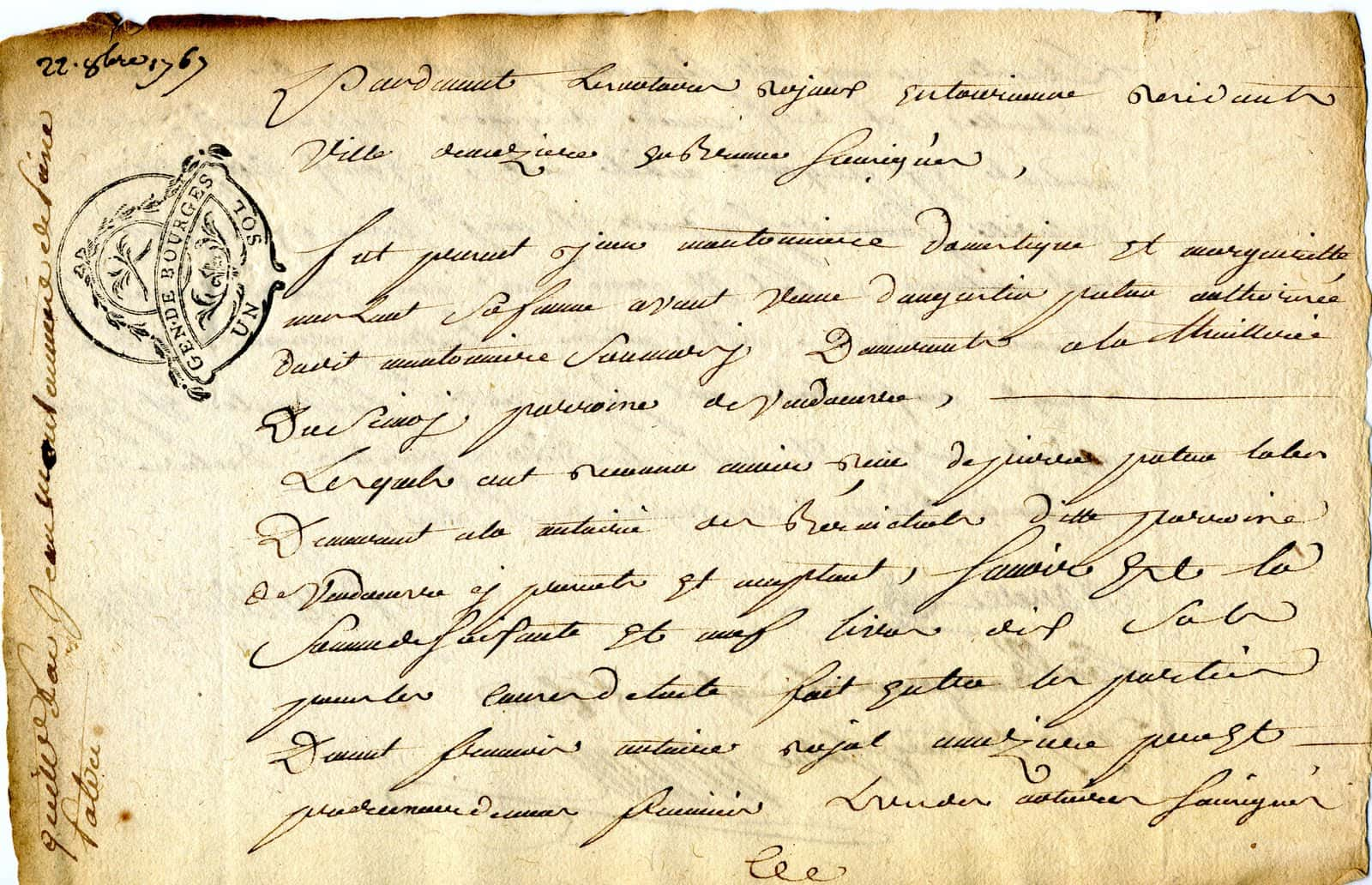

4. Mom to the Rescue

De Sade's mother-in-law got the king to write a lettre de cachet for de Sade for the Keller incident, which ordered his immediate imprisonment without trial, bypassing the courts. Although this seems cold-hearted, lettres de cachet were actually often requested to prevent dishonoring an aristocratic family in a drawn-out trial.

3. Crossing Lines

The Marquis' first serious charge was a doozy: he tried to convince a sex worker to use holy crosses during their wanton acts. She reported him, as the act was rather blasphemous, which led to his first arrest. But after he was released, his romps continued.

2. The Night I Lost My Head

L.J. Ramon, a doctor who felt sympathy for Sade, removed his skull in order to perform phrenological studies on it. Unfortunately, Ramon gave the skull to a colleague, who then reportedly ran off with it. However, there's a rumor that the good doctor made a cast of Sade's cranium before leaving Paris, and that the artefact may be intact to this very day.

1. Cinephile

The 1975 Italian-French film Salo is loosely based on de Sade's manuscript The 120 Days of Sodom. In the film, libertines kidnap eighteen teens, and the work explores the abuse of power of the Republic of Salo era.