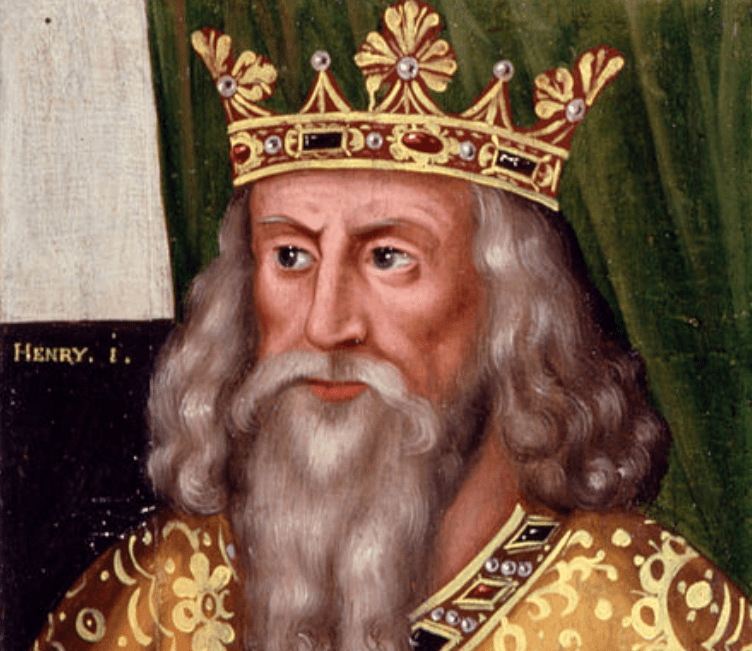

As the youngest son of William the Conqueror, Henry I was not likely to become king. Nevertheless, he outlived, outfought, or outwitted his older brothers to become the king of England in 1100 CE. Henry proved to be a master politician—but then his death plunged England into a civil war. Here are 50 anarchic facts about King Henry I of England.

1. Last in Line

There are few certain details about the birth of the future King Henry I. He was born in either 1068 or 1069. He may have been born in Selby, a town in Yorkshire, England. We do know that he was the youngest of four sons born to William the Conqueror and Matilda of Flanders. As the youngest of four sons, Henry’s rise to the throne was both unlikely and unpredictable.

2. Cut From the Same Cloth

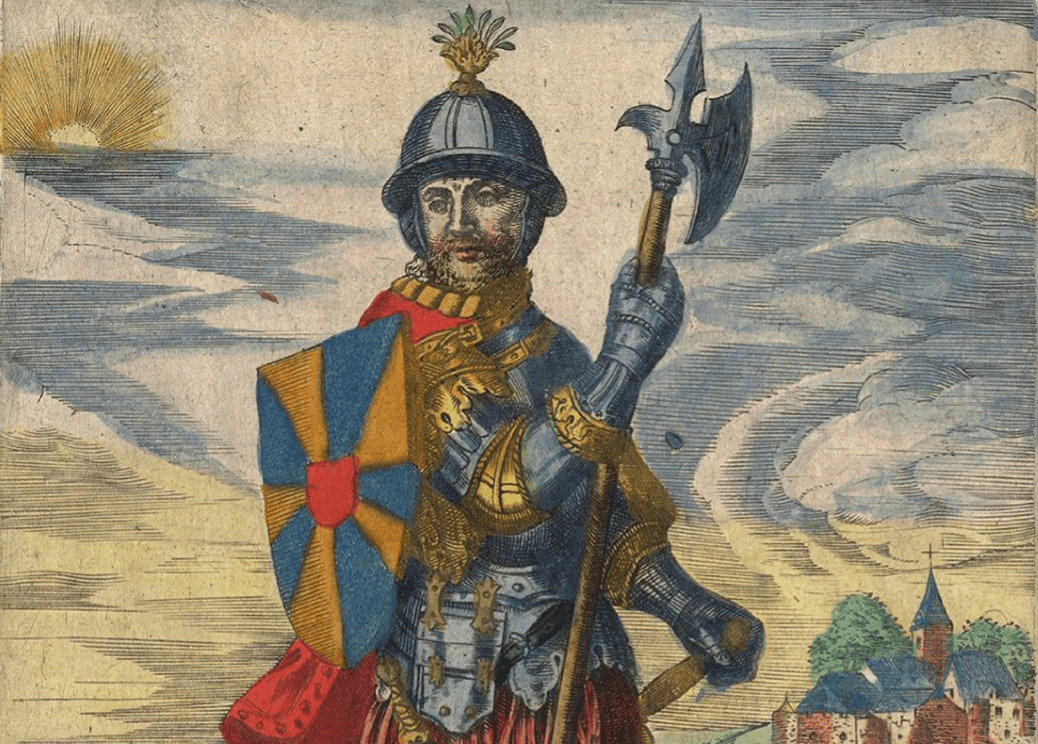

Henry’s father was William I, usually called William the Conqueror. The illegitimate son of a Norman duke, William invaded England in 1066, overthrowing King Harold II, and consolidating England and Normandy. William’s deciding victory, the Battle of Hastings, is depicted in the Bayeux Tapestry.

3. On His Mother’s Side

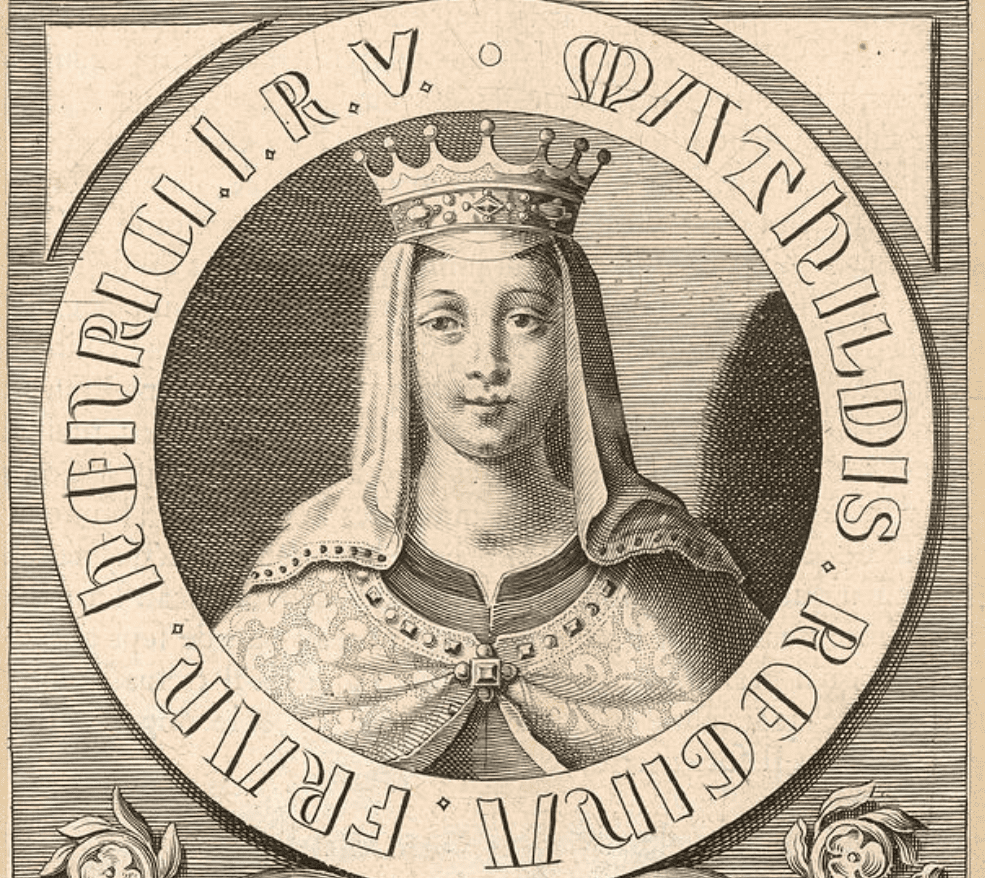

Henry’s mother was Matilda of Flanders. She was the granddaughter of France’s King Henry I, for whom Henry was named. Matilda was of higher birth than the illegitimately born William, and initially refused to marry him on that account—but history shows the two had a loyal and loving marriage which resulted in 10 children.

4. The Philosopher King

For the last-in-line Henry, education would be very important. Matilda secured the tutoring services of Osmond, the Bishop of Salisbury and Chancellor to the King. With his religious education, trained in Latin and the liberal arts, Henry seemed destined to become a clergyman. Henry, apparently, had other plans.

5. A Piece of the Pie

Henry’s older brother Richard died in a hunting accident when Henry was just six. When William died in 1087, he split his possessions between his two oldest sons, leaving Normandy to his eldest, Robert Curthose, and England to his favorite, William Rufus. Henry received a sum of ₤5,000 pounds and two small parcels of land in Buckinghamshire and Gloucestershire.

6. Sibling Rivalry

Henry might have been left with a relatively small share of his inheritance, but it was Robert who was most upset with the division. Robert gathered together a group of sympathetic noblemen to help him overthrow William Rufus and seize England for himself. This put Henry in a predicament: his land was in England, but his money was in Normandy.

As his two brothers fought, Henry remained on the sidelines, not willing to risk taking sides.

7. Pass the Duchy

As his invasion began to falter, Robert made an offer to Henry: if Henry would give Robert ₤3,000, Robert would give Henry a small corner of Normandy for his very own. Henry took the deal, and soon proved himself a much more capable and organized leader than Robert. Henry was now in charge of his own duchy, but Robert and William were both growing mistrustful.

8. My Brother’s Keeper

Henry’s skillful leadership made him popular among the Norman nobility. Robert, sensing that his grip on the region was slipping, tried to renege on the deal. He imprisoned Henry for most of 1088, before the local nobility demanded his release. Robert released Henry, but his refusal to restore Henry to power only further eroded his control over Normandy.

9. Common Frenemy

Now formally titled, Henry continued to consolidate his power among Normandy’s landowners. This naturally aroused the suspicion of his brothers, Robert and William, and when the two finally signed a truce in 1091, they turned their efforts toward putting Henry in his place. Henry gathered together an army of mercenaries.

They went on to meet the armies of Robert and William in a number of skirmishes throughout western Normandy.

History's most fascinating stories and darkest secrets, delivered to your inbox daily.

10. Thicker than Water

A pivotal point in the feud came when Henry met his brothers at Mont Saint-Michel in 1091. Henry’s army ran out of fresh water, and Robert graciously allowed the army past to replenish their supply. This led to an argument between Robert and William—a rift that foreshadowed the end of their truce.

11. Role Reversal

With the support of several wealthy landowners and the help of his mercenaries, Henry seized control of the town of Domfront in 1092. Impressed, William (who, by now, had completely fallen out with Robert), began to offer Henry his support. Henry built a stronghold at Domfront and began to plan a campaign against Robert.

It would allow him to seize total control of Normandy.

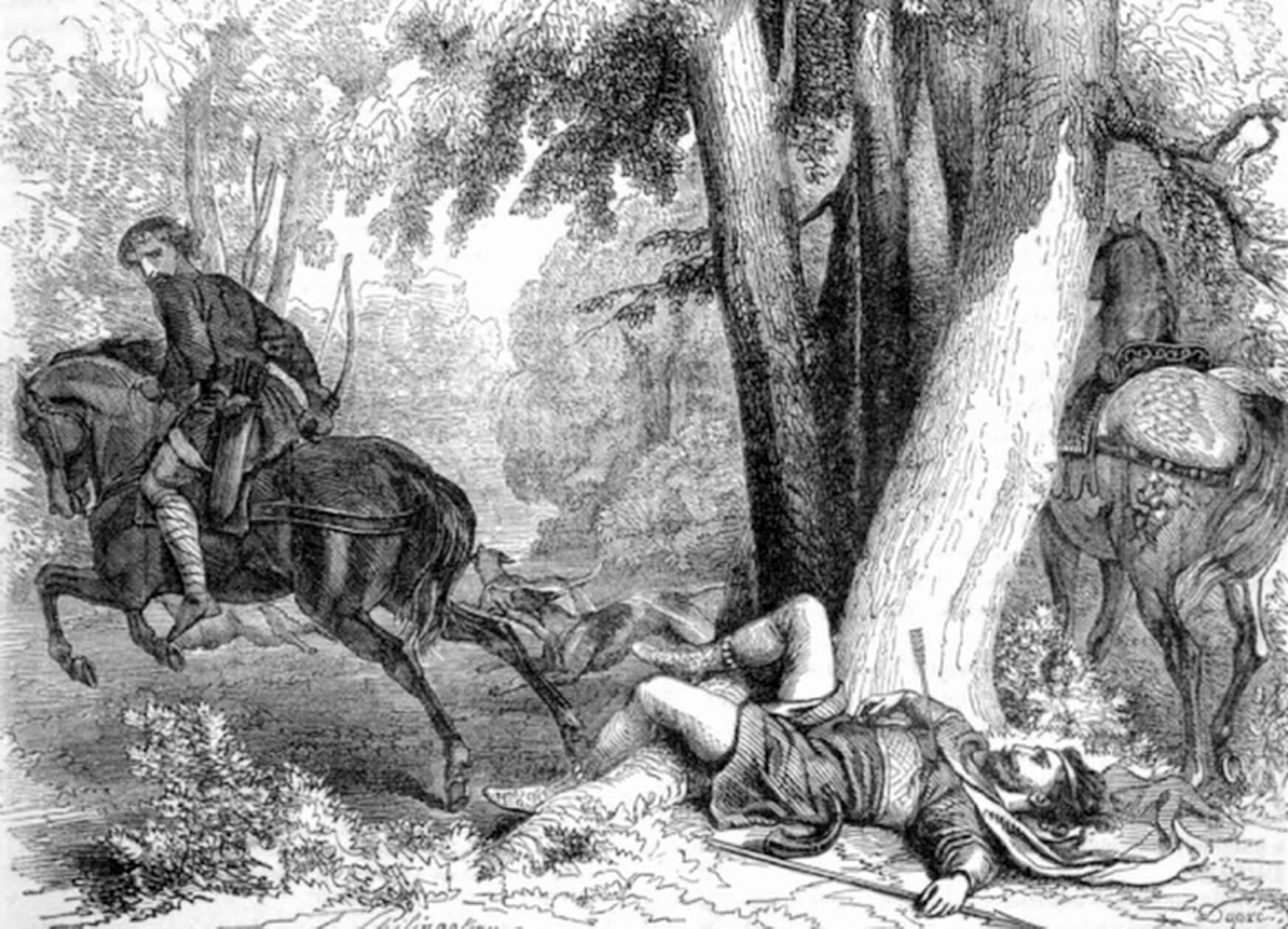

12. A-Hunting We Will Go

In 1100, with Robert away on the Crusades, Henry and William took a hunting trip together in New Forest, South Hampton. During the hunt, William was struck and killed by an arrow. Naturally, such a death was suspicious—the man accused of firing the arrow, Walter Tirel, fled to France immediately after—but most historians agree that it was merely an accident.

Either way, it was a stroke of luck for Henry.

13. Crowning Achievement

With William dead and Robert in the Holy Land, Henry saw a prime opportunity to seize the throne of England for himself. Henry’s claim was buoyed by the argument that he had been born to a reigning king and queen; Robert had been born in 1051, before William the Conqueror rose to power. Armed with a strong argument, not to mention the support of numerous noblemen and mercenaries, Henry was crowned King of England on August 5, 1100.

14. A Rose by any Other Name

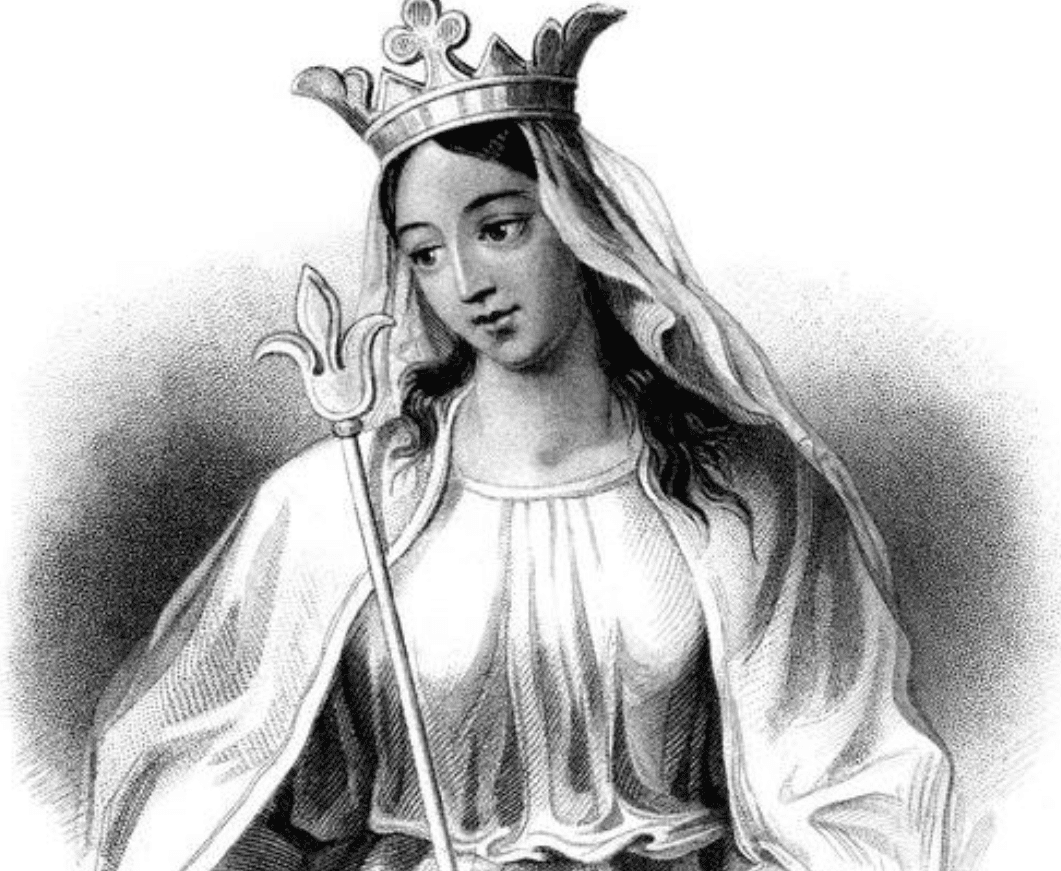

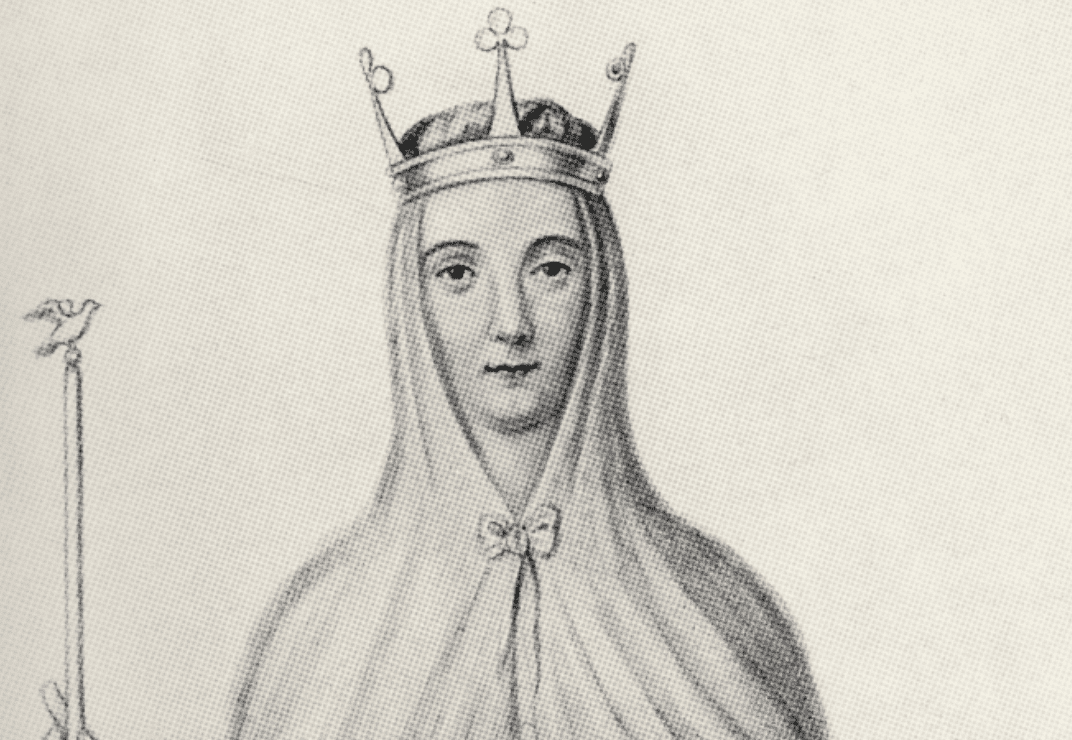

Shortly after his coronation, Henry married Edith. Edith’s father was the king of Scotland and her mother was a literal saint. She was well-educated, showed a keen interest in the arts, architecture, and medicine, and was deeply concerned for the sick and the poor. One the other hand, her name was Edith. Upon her coronation, the new queen was given the esteemed Norman name “Matilda.”

15. All in the Family

Edith may have been inspired to take the name Matilda because it was the name her godmother: Henry’s mother, Matilda of France.

16. Nun of Your Business

There was one obstacle that delayed Henry and Matilda’s marriage. From childhood, Matilda had been raised in a monastery where her aunt, Cristina, was a nun. There was some speculation that Matilda had been a nun herself, and therefore, ineligible for marriage. A council of bishops debated the matter and concluded that, while Matilda had worn a veil, she had never been ordained as a nun.

She was, therefore, free to marry if she wished.

17. My Fair Lady

Matilda was a popular queen, though she and Henry were sometimes mocked for being “old fashioned” and “rustic” compared to their Norman predecessors. Some historians believe she may have been the “fair lady” alluded to in the song “London Bridge is Falling Down.” Together, Henry and Matilda had two children: Matilda, who became Holy Roman Empress, and William, Duke of Normandy.

18. The Lawmaker

Matilda also played an active role in Henry’s court. She personally issued 31 charters or writs during her reign.

19. Baby Mama Drama

Henry, however, was not as loyal to his wife as his father had been to Henry’s mother. In fact, Henry is reckoned to have fathered more illegitimate children than any English king before or since, with some estimating that Henry had more than 24 children by various mistresses.

20. You Mad, Bro?

When Henry’s brother, Robert Curthose, returned from his crusade in 1101, he was understandably upset. Robert was, after all, the older brother and entitled to be king. Robert gathered together an army and invaded England, but Henry managed to negotiate a peace: in return for the right to rule England, Henry would give Robert control of Normandy, a massive annual income of ₤2000.

He was also promised that if Henry died, Robert would inherit the throne.

21. Alone at Last

With Robert effectively neutralized and installed in Normandy, Henry set about his next order of business: seizing Normandy. Henry marched into Robert’s territory. After a series of conquests and sieges, the two brothers met at the Battle of Tinchebray in 1106. Henry was victorious, and Robert, the eldest son of William the Conqueror, spent the remainder of his life in prison.

22. Son of a Gun

Robert’s son, William Clito, was just three years old when Robert was imprisoned. Twice he tried to avenge his father by launching rebellions against Henry. Both times, William Clito was defeated and settled for a title as the Count of Flanders.

23. Hand It Over

Henry’s ongoing campaigns in Normandy stretched his finances to their breaking point. To make matters worse, his minters were making coins of very poor quality. In response, Henry passed down a violent punishment: every minter in England would not only lose their right hand but be castrated as well.

24. 'Tis Better to Give Than to Receive

This grim punishment was carried out by Roger, the Bishop of Canterbury, and at Christmastime no less. Perhaps moved by the spirit of the season, Roger spared at least one of the minters—for a small fee of ₤20.

25. The Taxman

Henry further supplemented his finances through taxation, administrative fees, and levying exorbitant fines on minor infractions. If, for example, a nobleman was getting married, he had to pay Henry for the privilege. It was a successful strategy: In 1130 alone, Henry raked in more than £24,000 cash, not to mention numerous payments in the form of livestock and vegetables.

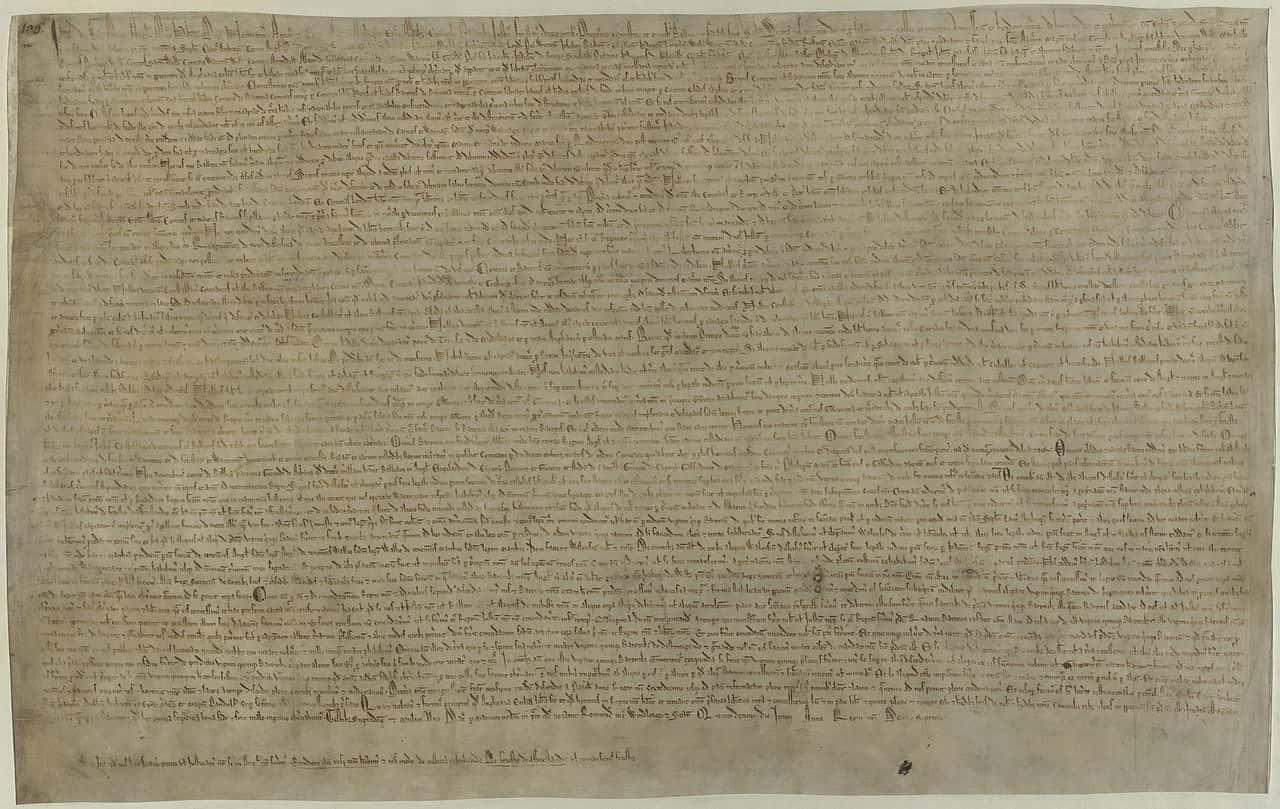

26. Carta-d Off

Henry’s passion for taxation was not shared by his successor, but subsequent kings expanded on Henry’s tax policies with such zeal that nobles began to protest. These protests led to the enactment of the Magna Carta in 1215.

27. Absolute Unit

It may come as no surprise, then, that tax-happy Henry was all about precision. In fact, he standardized the “ell,” a unit of measurement used by clothiers and fabric makers. Prior to this, the equivalent length of the ell was left to the whims of each individual clothmaker. Henry standardized it as the length of his forearm, from the tip of his middle finger to his elbow.

28. Nobody Nose for Sure

Some medieval chroniclers suggested that the yard was also based on Henry’s measurements. Supposedly, the original yard was the distance from the thumb of Henry’s outstretched arm to the tip of his nose.

29. What’s in a Name?

Henry is sometimes known by the name Henry Beauclerc. The surname—French for “good scholar”—acknowledges Henry’s advanced education and administrative skill.

30. The Chosen People

Henry’s reign saw the beginning of the acceptance of Jews into English culture. Henry passed a royal charter which gave Jews the right to move freely about the country, sell and own property, and be tried by a jury of their peers. Moreover, the oath of a Jewish person was given the weight of the oaths of 12 Christians.

31. Let My People Go

That’s not to say that antisemitism disappeared during Henry’s reign; indeed, Jews were only afforded these rights because the charter recognized them as “sicut res propriæ nostræ”—essentially, property of the king.

32. By Divine Right

Henry may have been tolerant of other religions, but he ran afoul of his own Christian church. Henry had made a practice of handpicking bishops and high-ranking clergymen in England, a right the Vatican claimed for itself alone. Henry was forced to abandon the practice when the Pope threatened him with ex-communication.

33. Other Plans

Henry spent much of his later reign feuding with Louis VI, the King of France, over the territories between France and Normandy. Henry was so preoccupied with fighting Louis VI that, when Matilda died in 1118, Henry did not attend the funeral.

34. The Second Wife

Henry later remarried. Adeliza Louvain was the daughter of Godfrey, Count of Louvain, and 35 years Henry’s junior. Though she and Henry were inseparable, she played little part in political proceedings and the couple failed to produce any children. When Henry died, Adeliza retired to a convent.

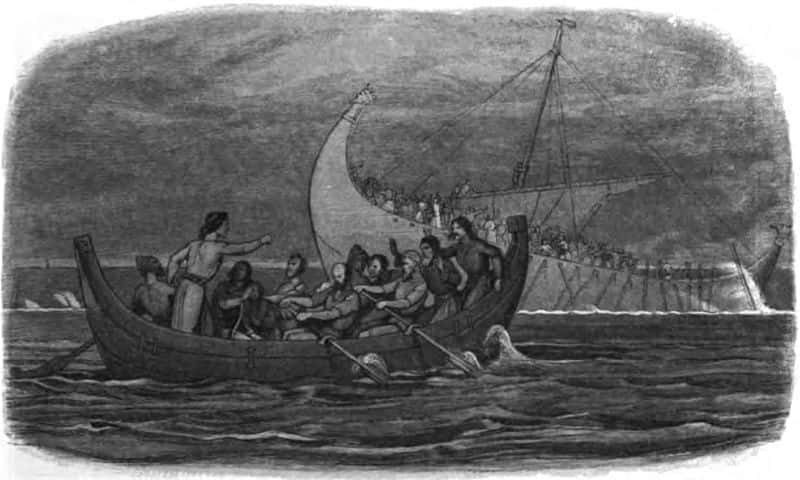

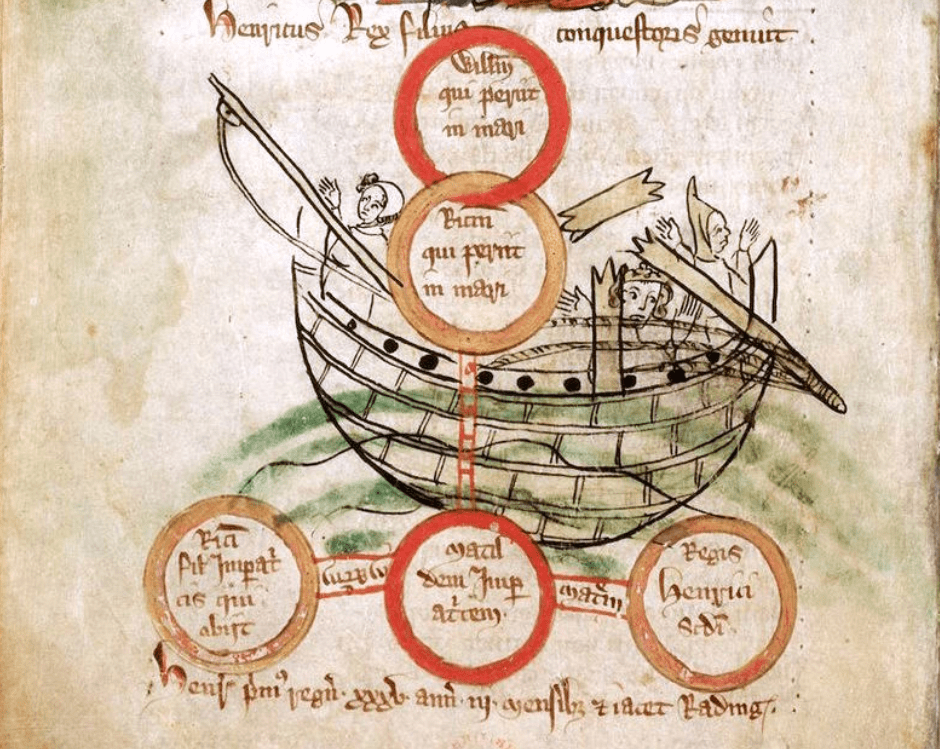

35. Booze Cruise

In 1120, a tragedy struck which would alter Henry’s legacy forever. Henry traveled from Normandy to England. His entourage—300 strong, including his heir, William—was expected to follow in the White Ship, captained by Thomas FitzStephen. By the time the White Ship set sail, her passengers had been drinking for several hours.

Their drunken behavior distracted FitzStephen such that the White Ship struck a rock and began to sink.

36. Sunk

William, the heir to the throne, managed to secure a lifeboat for himself. He might have been saved had he not gone back to rescue his half-sister, Matilda. As he rowed toward her, dozens of drowning nobles latched onto the lifeboat, capsizing the boat and drowning William as well.

37. The Captain Goes Down with the Ship

Of the passengers and crew of the White Ship, only one person survived: a butcher named Berold. Some historians claimed that the captain of the White Ship, Thomas FitzStephen, also surfaced but, upon learning William had perished, chose to drown himself rather than face the king.

38. She’ll Have to Do

With his only legitimate son dead, and having failed to produce another to replace him, Henry recalled his only remaining legitimate child, Matilda, from the continent. Matilda’s husband, the Holy Roman Emperor Henry V, had recently died, and Henry I hoped that his subjects would accept Matilda as an adequate successor.

39. Breaking Up is Hard to Do

To strengthen Matilda’s appeal, Henry married his daughter to Geoffrey of Anjou. This marriage proved unstable at first—at one point, Matilda and Geoffrey even separated. But Henry managed to convince them to reconcile, and they would go on to have two sons, Henry and Geoffrey.

40. A Meal Fit for a King

Like all kings, Henry loved a good feast. His favorite meal by far was lamprey—an eel-like fish that latches onto other fish and drains their blood. Henry’s fondness for lampreys was so pronounced that his physician had to warn him not to eat so many, as the rich meat was bad for his health.

41. Eat Your Heart Out

Henry failed to take his physician’s advice, however. Henry died on December 1, 1135, while on a hunting trip in Lyons-la-Forêt, Normandy. The cause? Apparently, a “surfeit” of lampreys eaten some nights prior.

42. By Popular Demand

Henry’s death resulted in a succession crisis throughout England. Though he had named Matilda as his successor, widespread support fell to his nephew, Stephen of Blois. Stephen had the support of both the church and the aristocracy and, on December 15, 1135, he was crowned King of England.

43. Promise Breakers

Ironically, Stephen of Blois was among the nobles of Henry’s court who took an oath promising to recognize Henry’s succession plans.

44. Paid Off

At the time, Matilda and Geoffrey were stalled in Anjou, unable to travel to England. In their absence, a new claimant came forward: Stephen’s older brother, Theobald. Theobald had the Normans’ support, but that support soon eroded when it became clear that supporting Theobald would lead to Normandy and England separating.

Theobald settled when Stephen offered him a large sum to not challenge for the throne.

45. Trouble from all Directions

Theobald was out of the picture, but a new challenger had arrived from the north. David I, Henry’s brother-in-law, began laying siege to the territories bordering Scotland. Meanwhile, Matilda and Geoffrey had enlisted the help of the Welsh and were attacking sites in Normandy.

46. Anarchy in the UK

With so many challengers for the throne coming forward, England and Normandy soon devolved into a full-blown civil war that lasted nearly 20 years. This period is referred to by historians as “the Anarchy.”

47. Peace at Last

The Anarchy went on for so long that Matilda and Geoffrey’s son, Henry, wound up the victor. In 1154, Stephen and Henry signed the Treaty of Winchester, which recognized Henry as Stephen’s adopted son and successor. This infuriated Stephen’s son, Eustace, but ultimately restored peace to the kingdom after decades of unrest.

Henry II, the first of the Plantagenet kings, reigned for 35 years and kicked off a dynasty that lasted more than 300 years.

Public Domain Pictures

Public Domain Pictures

48. Dear Abbey

Henry was buried at Reading Abbey, but the exact site was lost in the 16th century when the abbey was demolished. In 2015, the team who rediscovered the remains of Richard III announced that they were setting their sights on Henry I next.

49. An Eye for an Eye

For the most part, Henry’s illegitimate children were loyal to him and did not cause him any trouble. One exception was Juliane, his daughter by a mistress named Ansfride. In 1119, Juliane’s husband, Eustace, fell into a dispute with a nobleman named Ralph Harnec; Eustace decided it would be a good course of action to blind Harnec’s son.

When Henry was presented with the case, he decided to put family aside and ruled that, as compensation, Harnec should be allowed to blind Juliane’s daughters and cut off their noses. Shocked at Henry’s decision, Juliane retaliated by trying to kill Henry with a crossbow.

50. When You Come for the King…

In contrast to her blinded daughters, Juliane received a light sentence for her attempted regicide. She was disinherited and spent the rest of her life in a convent.

Sources: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16