Monument Of The Ancients

Standing on a rise on the Salisbury Plain of southern England, Stonehenge is one of the most recognizable monuments in the world. Its circle of carved vertical pillars supporting horizontal stone slabs are not only a magnet for tourists, but for archaeologists as well. But how was Stonehenge built?

Stonehenge Basics

Stonehenge was built between 3100–1600 BC. This makes it older than the Egyptian pyramids. Situated on Salisbury Plain in the midst of the biggest series of Bronze Age burial mounds in England, the monument is aligned toward the sunrise on the summer solstice, and sunset on the winter solstice.

The People Of Stonehenge

Who built Stonehenge? The DNA evidence suggests there were waves of human migration from mainland Europe and the Middle East starting at around 4000 BC. These migratory people were farmers, who replaced and interbred with the nomadic hunter-gatherers living in Britain since the end of the last Ice Age. The best evidence suggests that this agrarian civilization was the one that built Stonehenge.

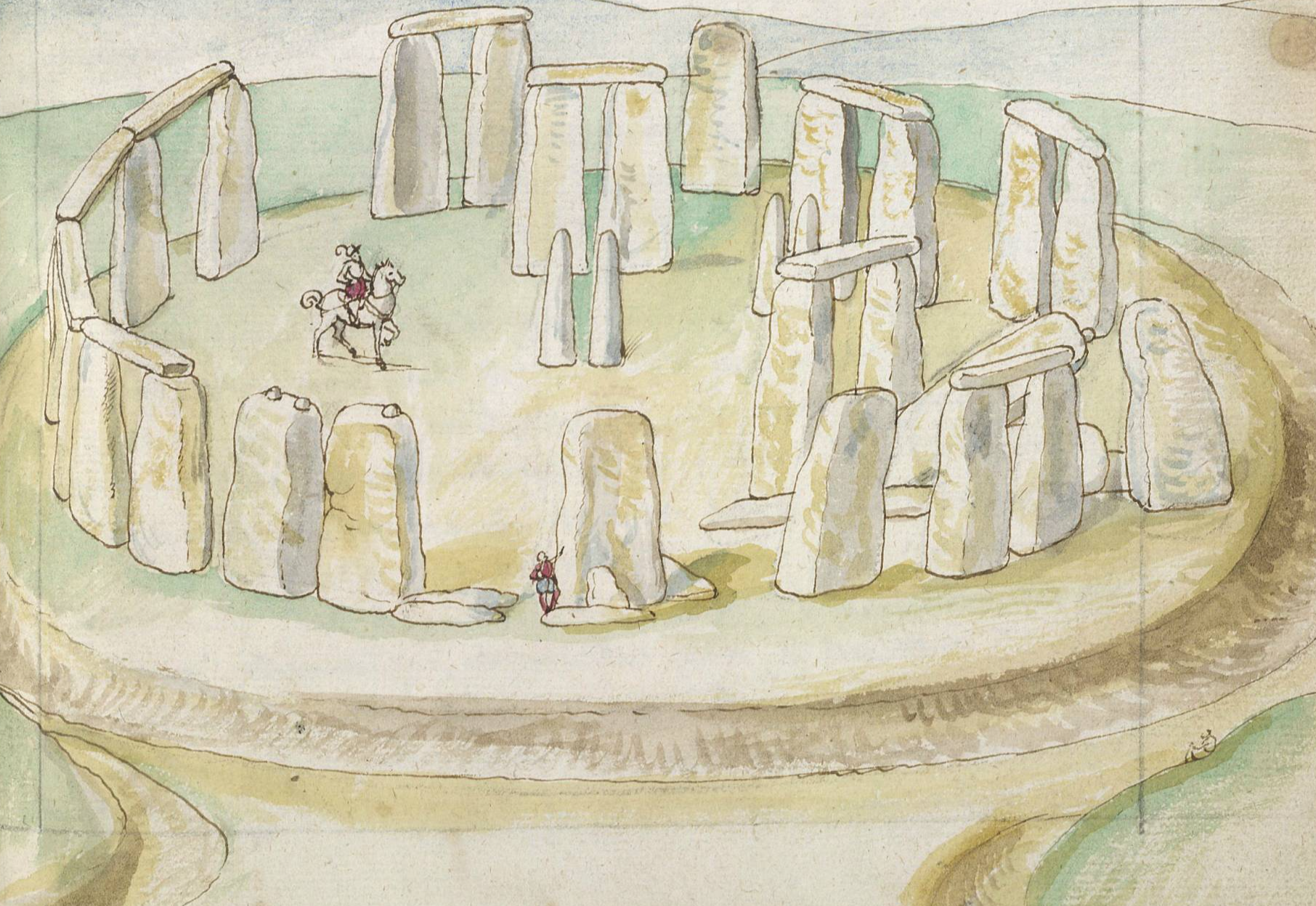

Lucas de Heere, Wikimedia Commons

Lucas de Heere, Wikimedia Commons

Parts Of Stonehenge: The Outer Circle

The outer circle of stones is the biggest and most identifiable feature of Stonehenge. These are vertical slabs of sandstone, called “sarsens”, topped by a once-continuous span of horizontal slabs. The pillars are 13 feet high on average, with the spanning slabs weighing around 25 tons apiece. Archaeologists estimate that there were originally 80 of the vertical stones, of which 52 still remain upright. The outer circle is about 100 feet across.

Cbuske46, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Cbuske46, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Parts Of Stonehenge: The Bluestones

Inside the ring of sarsens is another ring of smaller stones called the bluestones. These stones are only eight feet tall and average about four tons each. These stones are darker and harder than the sarsens, and were positioned vertically but stood separately without spanning lintels. The source and function of the bluestones is one of the most active topics in current Stonehenge research.

Anita van den Broek, Shutterstock

Anita van den Broek, Shutterstock

Parts Of Stonehenge: The Central Horseshoe

The center of Stonehenge consists of a series of separate monuments known as trilithons. These are pairs of enormous vertical slabs spanned by a horizontal lintel. There are five trilithons arranged in a horseshoe pattern. Unlike the outer ring, the trilithons were never meant to be continuous. They are about 20 feet high.

TobyEditor, CC BY 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

TobyEditor, CC BY 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Parts Of Stonehenge: The Circular Ditch

The stone monuments of Stonehenge sit in the middle of a circular ditch that is 330 feet in diameter. The ditch has a low outer bank and high inner bank. There were originally two entry paths into the circle: a main entrance on the Northeast side, and a narrower path on the South side.

Parts Of Stonehenge: The Aubrey Holes

The Aubrey Holes are a series of 56 pits forming a circle around the inside edge of the circular ditch. Each pit is about three feet in diameter. Researchers are still not clear what their purpose is, but the holes are thought to have once held stone columns or wooden posts. The location of the Aubrey holes is currently marked off with concrete circles.

Adamsan (talk) (Uploads), Wikimedia Commons

Adamsan (talk) (Uploads), Wikimedia Commons

Stage One Of Construction: Forming The Circle

The first stage of construction at Stonehenge took place at around 3100 BC. This consisted of digging the circular ditch with its original entryways into the circle. The 56 Aubrey Holes also date from this time period. The bottom of the ditch was filled with bones of deer and oxen that predate the age of the bone tools used to dig the ditch. With the circle complete, the builders of Stonehenge had laid the groundwork for millennia to come.

Sumit Surai, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Sumit Surai, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

History's most fascinating stories and darkest secrets, delivered to your inbox daily.

Stage Two Of Construction: Burial Ground

Stonehenge entered a quiet period at around 2900 BC, lasting 300 years. Numerous postholes were dug, some with parallel alignment, others clustered, and others seemingly randomly. Abundant human remains in the postholes, ditch, and Aubrey Holes suggests that the Stonehenge site was used as a cemetery in this period.

Wirestock Creators, Shutterstock

Wirestock Creators, Shutterstock

Stage Three Of Construction: The Main Body

The time from 2600 BC to 2300 BC marked the phase of the construction of the stone monuments we know today. Stonehenge was a beehive of activity. The main ring of sarsen stones, the central horseshoe of trilithons, and the bluestones were all emplaced in this period.

TobyEditor, CC BY 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

TobyEditor, CC BY 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Stage Four Of Construction: The Final Touches

The last elements to be added to the monument were two concentric rings of pits surrounding the outer sarsen ring. These were dug around 1900–1600 BC, and are known as the Y and Z holes. Since these holes were dug centuries after the main stone structures were built, their purpose remains uncertain.

Sources Of Stone: Sarsen Stones

Research indicates that the sarsen stones all come from a common source in the West Woods, near the Marlborough Downs in Wiltshire. This quarry location lies about 15 miles north of Stonehenge.

Peter Trimming, Sarsen Stones at Stonehenge, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Peter Trimming, Sarsen Stones at Stonehenge, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Sources Of Stone: Bluestones

The latest scientific work locates the source of the bluestones in two quarries in the Preseli Hills of southwestern Wales, 150 miles west of Stonehenge. This transport distance is farther than that of any other Bronze Age monument in Europe. The discovery also cast doubt on the longtime theory that the stones were transported by the Bristol River, as the overland route to Stonehenge is more direct.

The Heel Stone

The Heel Stone is an angular unshaped sarsen stone standing on its own, about 250 feet from the center of Stonehenge. The stone stands about 15 feet high and is buried four feet into the ground. It sits inside its own small circular ditch, similar to the main part of Stonehenge.

Nigel Thompson, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Nigel Thompson, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Station Stones

The Station Stones are the two remaining stones of an original series of four that formed a rectangle with its center right in the middle of the main monument. The stones are rough boulders about four feet high. The Station Stones are generally considered to be set up according to some astronomical alignment.

Alan Hunt, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Alan Hunt, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Altar Stone

The Altar Stone is a partially buried flat-lying stone in the center of the monument. It is overlain by a sarsen stone at a right angle. Though the research consensus is that the sarsen fell on its own, the Altar Stone’s central location has given it its nickname, alluding to its possible function. Once considered to be related to the bluestones, recent research sources the Altar Stone to a quarry in northeastern Scotland.

The Stones of Stonehenge, CC BY 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Stones of Stonehenge, CC BY 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Slaughter Stone

This is a fallen sarsen stone that lies halfway between the Heel Stone and the center of the monument. The red color of the pooled rainwater on the stone falsely led people to believe that human sacrifices were once carried out there, but it’s actually the iron deposits of the stone that gives the water a red color.

Stefan Kühn, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Stefan Kühn, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Transporting The Stones: Competing Theories

The size and weight of the stones at Stonehenge and the long distances they had to travel has generated lots of theories on how the people of ancient Britain may have moved them. The theories we have are limited by the materials and technology available to the builders, and the fact that terrain changes significantly over thousands of years.

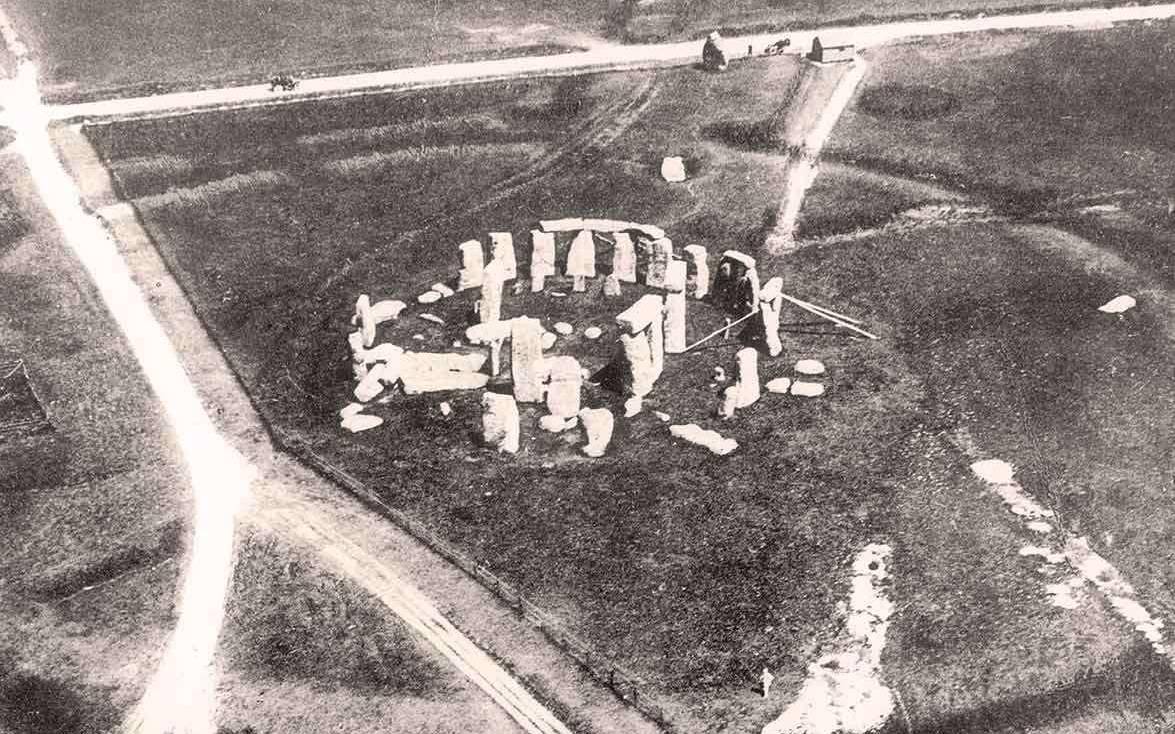

Philip Henry Sharpe, Wikimedia Commons

Philip Henry Sharpe, Wikimedia Commons

Transporting The Stones: Glacial Transport?

Since the sources of the stones lie north of the monument, some people think the stones were transported closer to Stonehenge by glaciers during the last Ice Age. The problem is that the most recent ice sheet stopped well to the north of the Salisbury Plain. More ancient ice ages happened so long ago that any transported stones would have been buried under many millennia of soil accumulation.

Stefan Kühn, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Stefan Kühn, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Transporting The Stones: Not A Gentle Ride

The region between the quarries and the Stonehenge site is quite hilly, crisscrossed by river valleys, and would have been swampy or densely forested in many places. Transporting stones the size of the ones at Stonehenge overland would have required some sort of roadway along which sledges or wheeled carts could have been dragged.

Transporting The Stones: Ancient Roads?

Research teams have been mapping and remote imaging the area between the quarries and Stonehenge in great detail for many years. Despite these efforts, no sign of any ancient roadway or track has ever been found leading to or from the ancient quarry sites—but the situation changes as we approach the vicinity of Stonehenge.

The Avenue

Stonehenge Avenue is a parallel pair of narrow ditches 34 meters apart that lead away from Stonehenge to the northeast before turning to the south where they approach the River Avon. The Avenue is dated to the time of the building of Stonehenge. Adjusting the location and water level of the Avon River 4500 years ago, the Avenue could represent the transport route of the bluestones.

Ashley Columbus, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Ashley Columbus, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Transporting The Stones: Ancient Waterways?

With the lack of evidence of cross-country roads, and the arduous task of dragging the stones over land, many researchers believe that the ancient builders of Stonehenge used water channels to transport the big blocks. The sarsen stones were so heavy that researchers doubt they could’ve been transported by water. The lighter bluestones could have been moved down the River Avon and other waterways, though.

Transporting The Stones: A Suitable Boat

The discovery of remnants of a plank boat near Ferriby, England sheds light on the kinds of boats that may have been used to transport the stones. While the boat dates from several centuries after the building of Stonehenge, the fact that the monument demonstrates joinery and accurate measurements shows it’s not unreasonable to think the ancients could make these boats as well.

Andrew Dunn, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Andrew Dunn, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Transporting The Stones: On The Water Or Under It?

Since transporting the stones on water would require sizable boats that take up space in narrow channels, some researchers have suggested that the bluestones could’ve been dragged under the water behind a boat using slings. However, a test of this unlikely theory during the Millennium Stone Project met with failure and a bluestone dropped to the bottom of the river.

Transporting The Stones: Did They Carry Them?

The problems of ancient construction have pushed researchers to experiment with different methods of moving large stones. An experiment in the 80s showed that a team of 24 people could carry a 2.5-ton block with ease using long flexible poles. This method could certainly be practical over short distances or getting around minor obstacles, etc.

Richmond times-dispatch, Wikimedia Commons

Richmond times-dispatch, Wikimedia Commons

Transporting The Stones: Sledges

Whether there was a roadway in place or not, the massive sarsen stones must’ve required some kind of sledge or roller system to transport them to the worksite. Modern calculations show that this transportation would’ve required hundreds of people to pull rope, lay logs along the route, etc.

National Geographic, Lost Cities with Albert Lin (2019-)

National Geographic, Lost Cities with Albert Lin (2019-)

Hoisting The Stones Into Place

There are a few different methods that could’ve been used to set the stones upright and lift the lintels up on top of them. A common theory is that A-frames and ramps made of timbers were used along with teams of workers pulling the stones into place with ropes. Another theory relies on levers and progressive shoring up of blocking to raise the stones. This possibility has recently been demonstrated by retired construction worker Wally Wallington.

Shaping The Stones: Tools

The stonemasons of Stonehenge likely used flint tools to shape the softer sandstone blocks and carve designs into them. Though the bluestones are harder, they too show evidence of being worked by flint tools. Flint had already been in use by early humans for thousands of years, and many flint fragments have been recovered from the ground around Stonehenge.

Shaping The Stones: Joinery

The lintel slabs of the outer sarsen circle were carved to fit together end-to-end in a tongue-and-groove pattern. The bottom faces of the lintel slabs were fitted to the tops of the uprights through a mortise-and-tenon pattern. The sides of the lintels were curved, and the uprights tapered to retain their perspective when viewed from below.

Pedro Cambra, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Pedro Cambra, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

A Prehistoric Worker’s Village

The Durrington Walls site was discovered in 2004, about two miles northeast of Stonehenge. Extensive digging at this site revealed a palisaded community that thrived with up to 4,000 people sometime between 2800–2100 BC. This village would have provided the formidable work force needed to move, shape, and lift the mighty stones into place.

Ethan Doyle White, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Ethan Doyle White, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Sarsen Stones Vs Bluestones

A key factor to consider for the Stonehenge construction is the different nature of the sarsen stones and bluestones. The bluestones were installed separately, so could be transported individually over a long period of time. The sarsen stones were tooled to be fitted together, so they had to be transported quickly in groups to be assembled at the Stonehenge site.

Frédéric Vincent, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Frédéric Vincent, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Why Were The Bluestones Chosen?

The bluestones were transported 130 miles from Wales to Stonehenge. Why were these stones so highly treasured? Some say it was just the stones’ color, workability, and other physical properties that marked their value. Others say the builders of the monument actually originated near the bluestone quarry and migrated to the Stonehenge site, while continuing to extract the bluestones for years afterward.

Prehistoric Society In Britain

By the time of the building of Stonehenge, the population of Britain may have numbered into the millions. The record shows that Bronze Age Britain was a complex society that carried on many different economic and religious activities within the islands and mainland Europe. Stonehenge is a monument to the enterprising nature of that early civilization, and may have been a way to unify the many communities then living in Britain

Learning From Other Sites

Salisbury Plain contains numerous other Bronze Age burial locations, which were mostly marked off by wooden monuments. The initial period of activity at Stonehenge indicates that it started out similarly as a wooden burial monument that was later built into the form that we’re all familiar with now. But did the purpose of Stonehenge change when the stones were built?

Purpose Of Stonehenge

The purpose of Stonehenge is still open for debate. The stones are aligned with the sunrise of the summer solstice and sunset of the winter solstice, so there is likely a religious significance to the site. Stonehenge could also have been used as an observatory for stargazing or as a calendar. The presence of the remains of people traced from other parts of Europe suggests that Stonehenge may have even been a pilgrimage destination or perhaps a place to seek healing.

Unusual Theories

Some find it difficult to accept the idea that ancient people understood how to do things that we haven’t figured out yet. This has led to a variety of unfounded theories—for example, that Stonehenge construction was supervised by extraterrestrials or giants lent a helping hand to transport the blocks. No serious archaeologists believe in these theories.

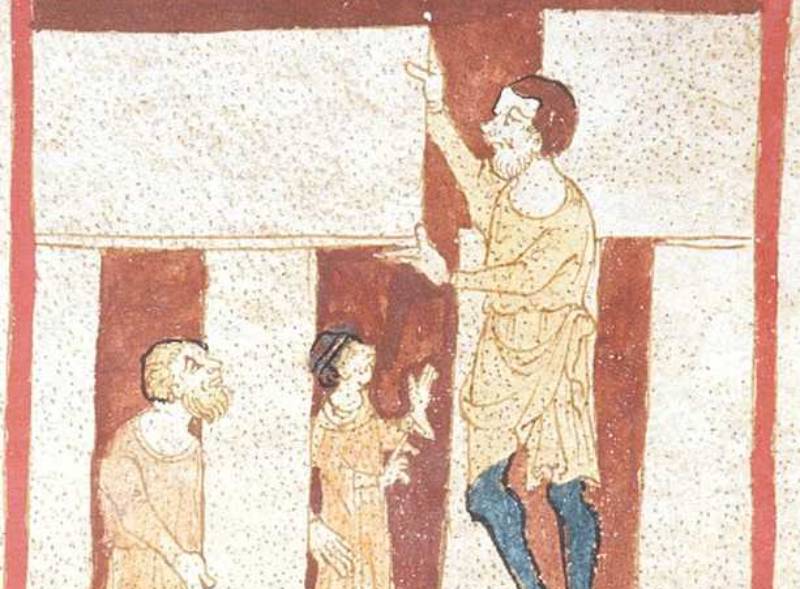

British Library, Wikimedia Commons

British Library, Wikimedia Commons

Disturbing The Ground

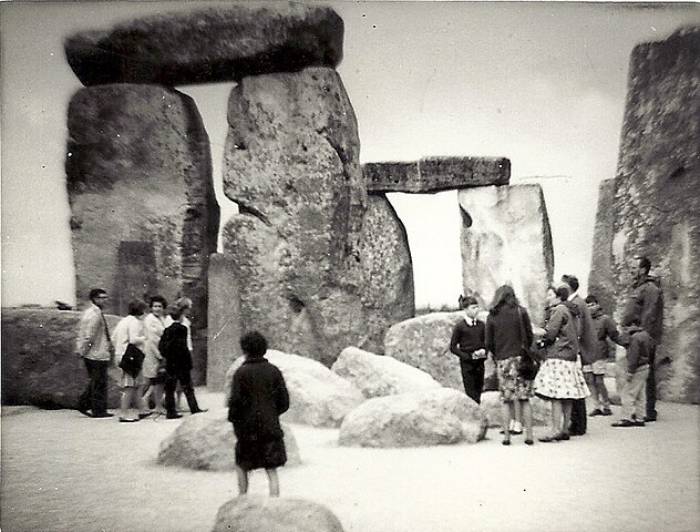

Through the centuries, several of the major stones have fallen over. The 20th Century saw extensive restoration work, including pushing the stones back upright. Unfortunately, a lot of the ground got trampled pretty badly, complicating the research work of archaeologists. Public access to the center of the monument is only allowed to small tour groups at specific times to minimize damage to the site.

Frank Parkes, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Frank Parkes, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Mystery Endures

While much has been learned in recent decades about the ancient world, the mists of time still guard their secrets jealously. There are lots of interesting theories on the transport of stones and the emplacement of the monuments, but to this day nobody knows exactly how the ancient people of Britain built Stonehenge.

Sanjay Nair, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Sanjay Nair, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons