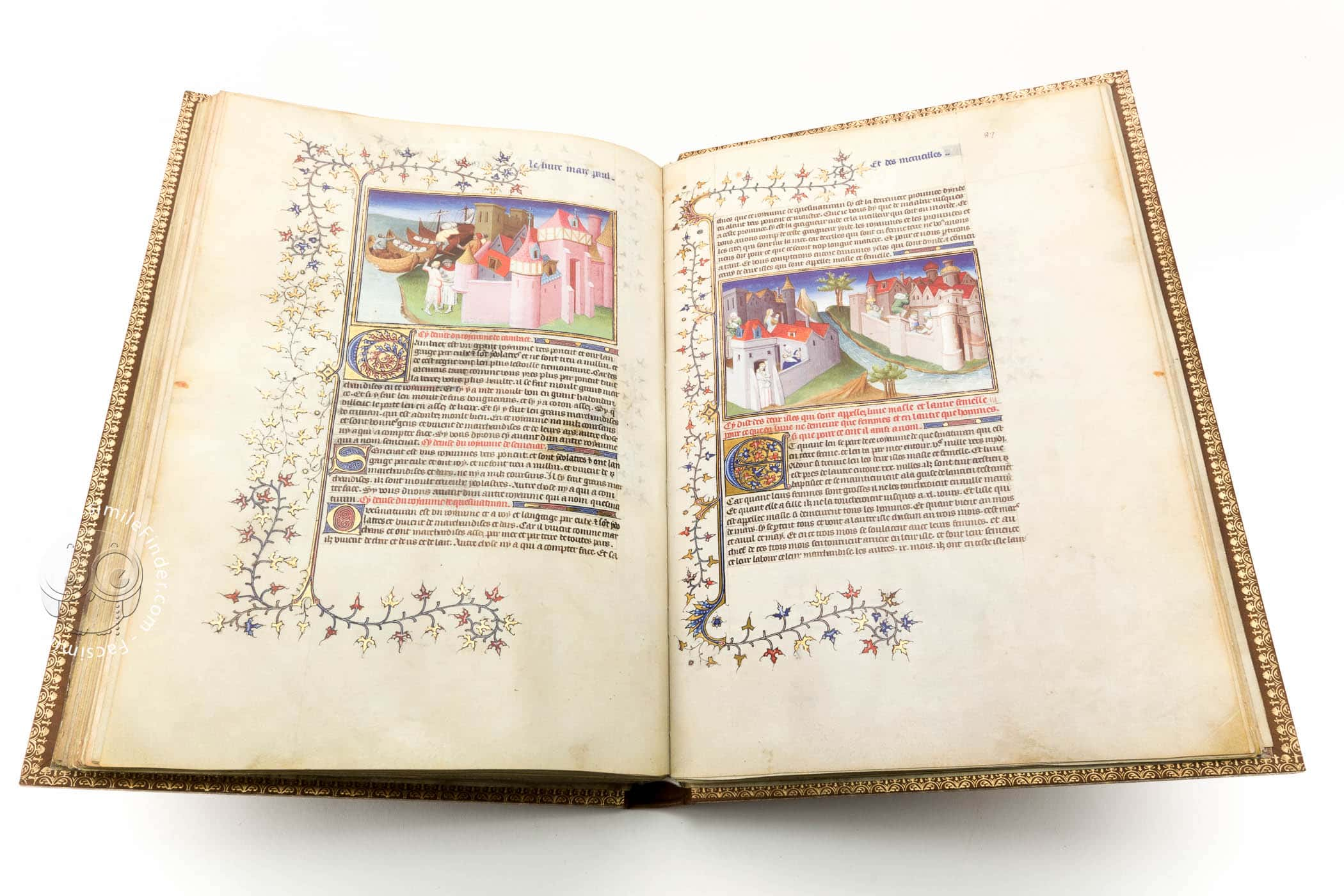

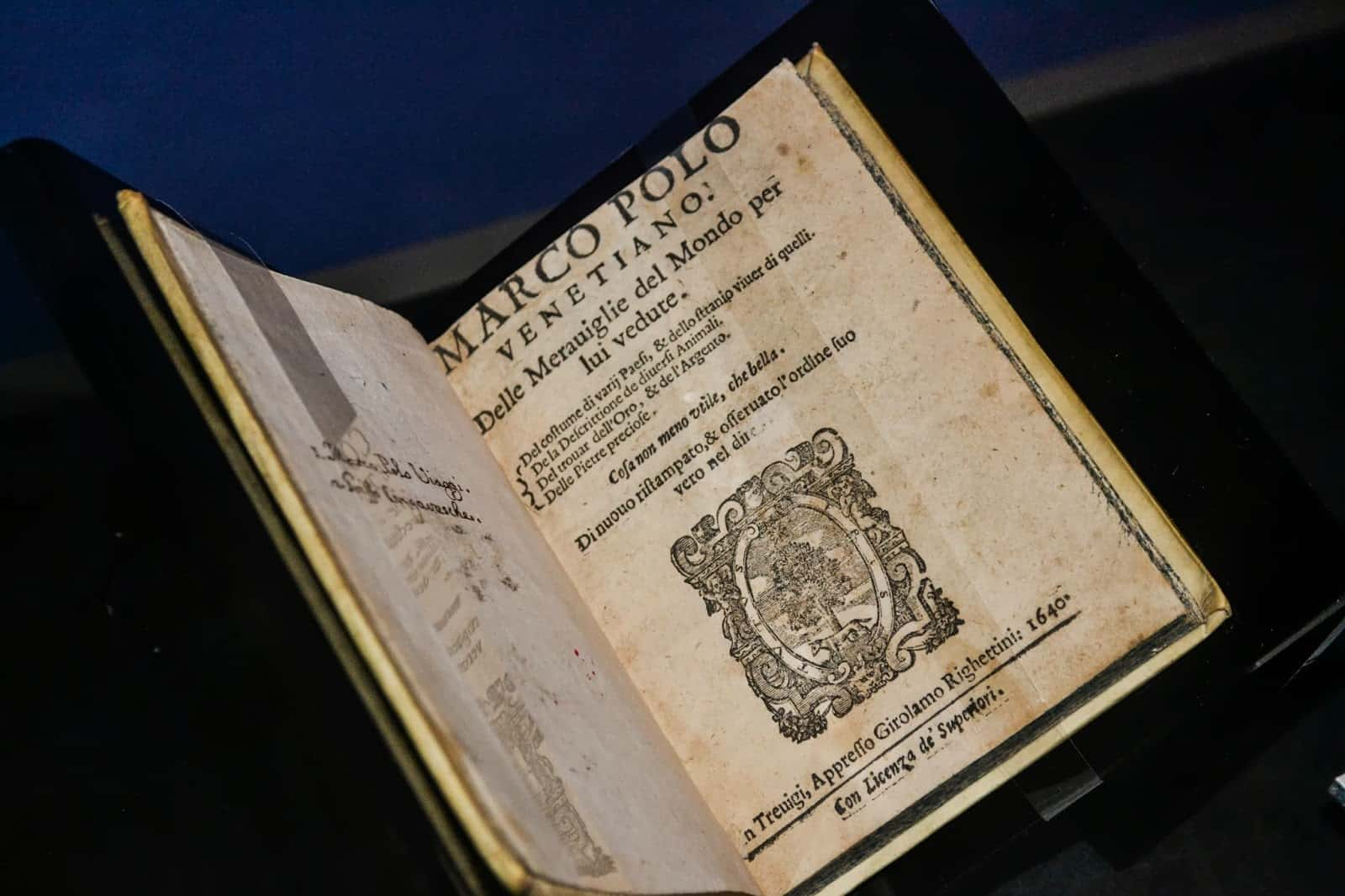

"I did not write half of what I saw, for I knew I would not be believed" —Marco Polo

Born in 1254 in Venice, Italy, Marco Polo set out on a journey to Asia with his father and uncle, and later chronicled his experiences. His book The Travels of Marco Polo was an inspiration for travellers such as Christopher Columbus. Below are 25 adventurous facts about the man behind the myth.

25. Teenage Traveller

When Marco Polo left on his Asian trip to the court of Kublai Khan with his father and Uncle, he was only 17 years old. The trip was probably the first time he’d journeyed away from home.

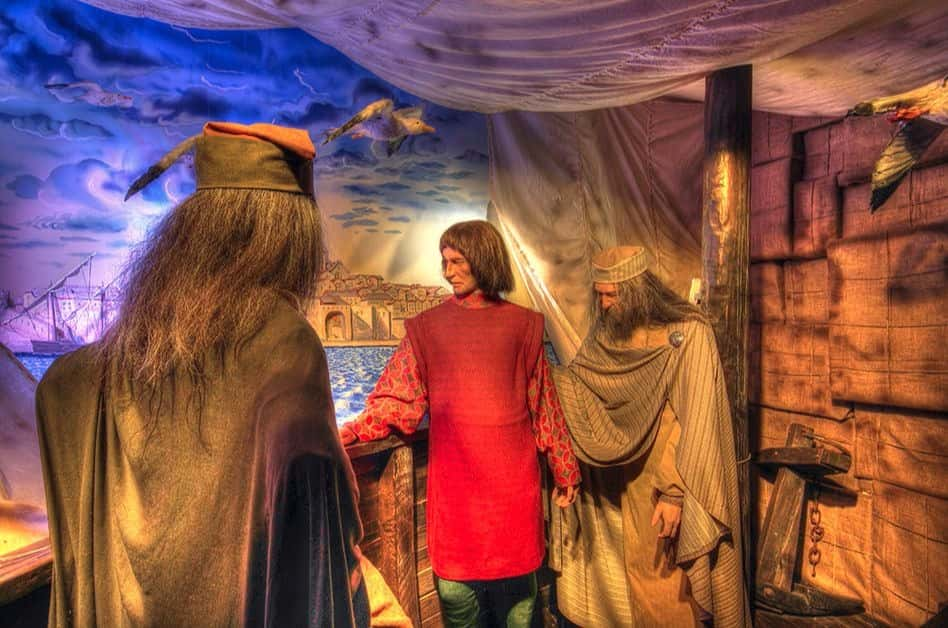

24. Jail Bird

In 1298, three years after his return, Polo was made a gentleman commander of a Venitian ship. His ship was captured during a battle between with the Genoese, and he was taken as a prisoner of war.

23. Ghostwriter

While in prison, Polo met Rustichello of Pisa. Rustichello was a famous romance writer, and Polo told his life story to Rustichello so he could write it down. When the two were released in 1299, Polo's name-making book was complete.

Pinterest

Pinterest

22. Murky Origins

Historians generally agree that Polo was born sometime around the year 1254, but they have often debated the exact date and location of his birth. The popular belief is that he was born in Venice, but some scholars think that he might have been born on the island of Korcula in what’s now Croatia. According to the theory, Polo’s father was not actually from Italy, and he changed his name from Pilic to Polo when he settled in Venice.

21. Mostly Parentless

Polo's mother died around 1260 when he was still a child. Little, however, is known about his childhood, and he was largely raised by his aunt and uncle.

Sources: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11

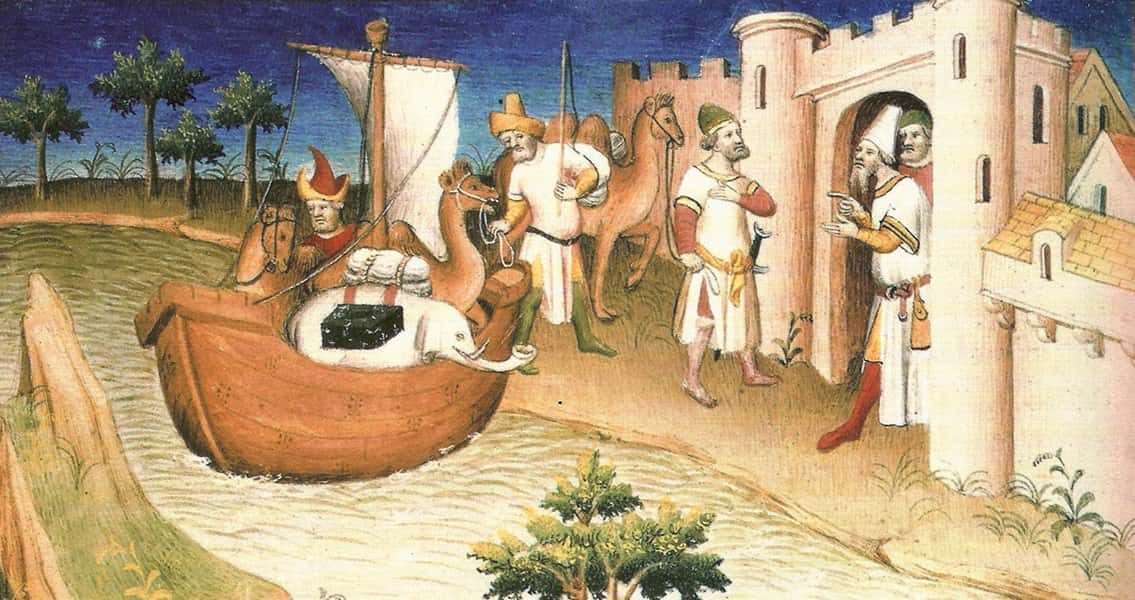

20. Return Journey

Polo’s journey to China marked the second time the Polos had visited Asia. His father Niccolo and uncle Maffeo had already travelled to the East—indeed, they were travelling when Polo was born in 1254.

19. Stranger Danger

When Polo set out with his father and uncle on their more extensive trip, he barely knew his companions: the brothers only returned home from their first trip in 1269, when Marco was already 15.

18. A Minor Setback

When the Polo brothers returned home in 1269, they discovered that Pope Clement IV had died. Hoping that a new Pope would be elected soon, they stayed in Venice for two years. When there was still no election, they started for the Mongol court. In what is now Israel, the papal legate Teobaldo of Piacenza entrusted them with letters for Kublai Khan—but then good old Teobaldo got elected Pope just days after the Polos left Israel, and the crew had to turn around to get proper credentials from now-Pope Gregory X.

On This Day In Messianic Jewish History

On This Day In Messianic Jewish History

17. Not a Quick Trip

The Polos originally planned to stay in Asia just a few years, but ended up staying much longer; Marco Polo was gone from Venice for a staggering 24 years.

16. Perilous Journey

The journey to Asia wasn’t easy, and Marco faced a number of challenges. While in what is now Afghanistan, he fell ill and was forced to take refuge in the mountains while he recovered. He also reported the difficulty of crossing the Gobi desert, writing that it took a month to cross it at its narrowest point.

Sources: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11

15. How Far Did They Go?

For years, historians have been questioning whether or not Polo did indeed make it to China. There’s no actual proof beyond his book that he made it that far, but the amount of detailed knowledge that Polo outlines in the book suggests that he almost certainly did.

14. The Myth of Spaghetti

One of the more popular legends about Polo’s travels is that he brought pasta to Venice from China. This isn't true, and pasta had been part of Italian cuisine since before Marco’s birth. He did, however, bring something even more revolutionary to Europe: the idea of paper money.

13. Not a Trailblazer

Polo wasn’t the first traveler to the Far East. In the 1240s, the Franciscan monk Giovanni da Pian del Carpini reached China and met with the Great Kahn. William of Rubruck then travelled east in the 1250s, aiming to convert the Mongols to Christianity.

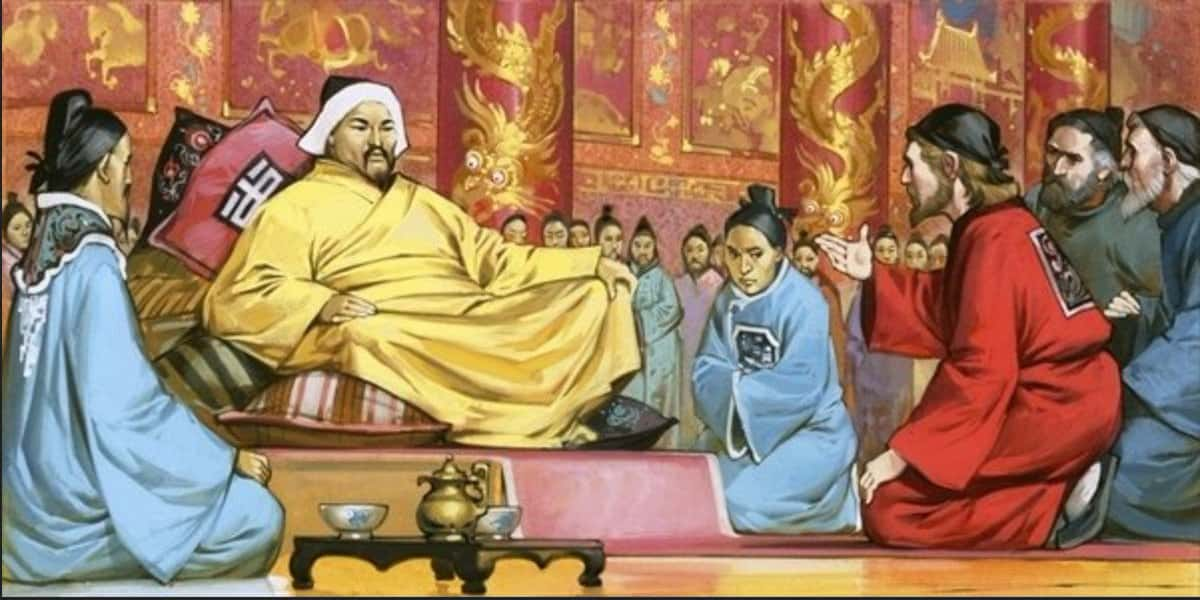

12. More than Traders

By trade, the Polos were merchants who sold rare items like silk, jewels, and spice, but their travels were not simply trading missions. Kublai Kahn first commissioned the trio to be emissaries, and Marco was later sent to China and Southeast Asia as a tax collector and as Kahn’s special messenger.

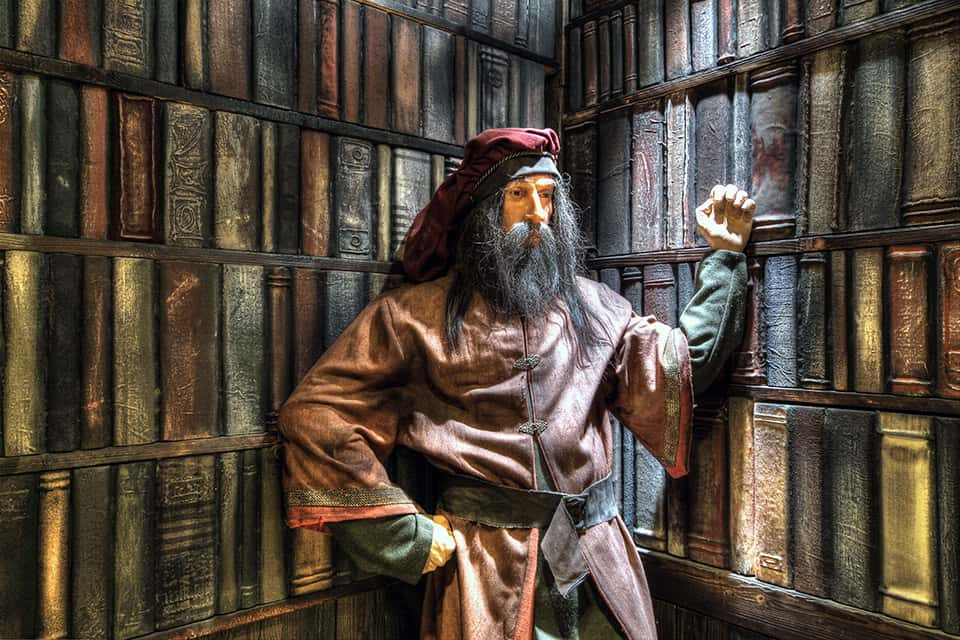

11. Learning the Language

Young Marco immersed himself in Eastern culture, customs, and language. He demonstrated a curiosity for his surroundings, and claimed to have learned four languages. Historians have speculated that these languages were probably Mongolian, Persian, Arabic, and Turkish. You'll note that Chinese isn't on that list!

Sources: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11

10. Polo’s Sheep

Several hundred years after his death, a species of sheep was named after the Polo. In his book, Polo mentions observing a mountain sheep in what’s now northeastern Afghanistan, and in 1841, zoologist Edward Blyth referred to a sheep called Ovis ammon polii.

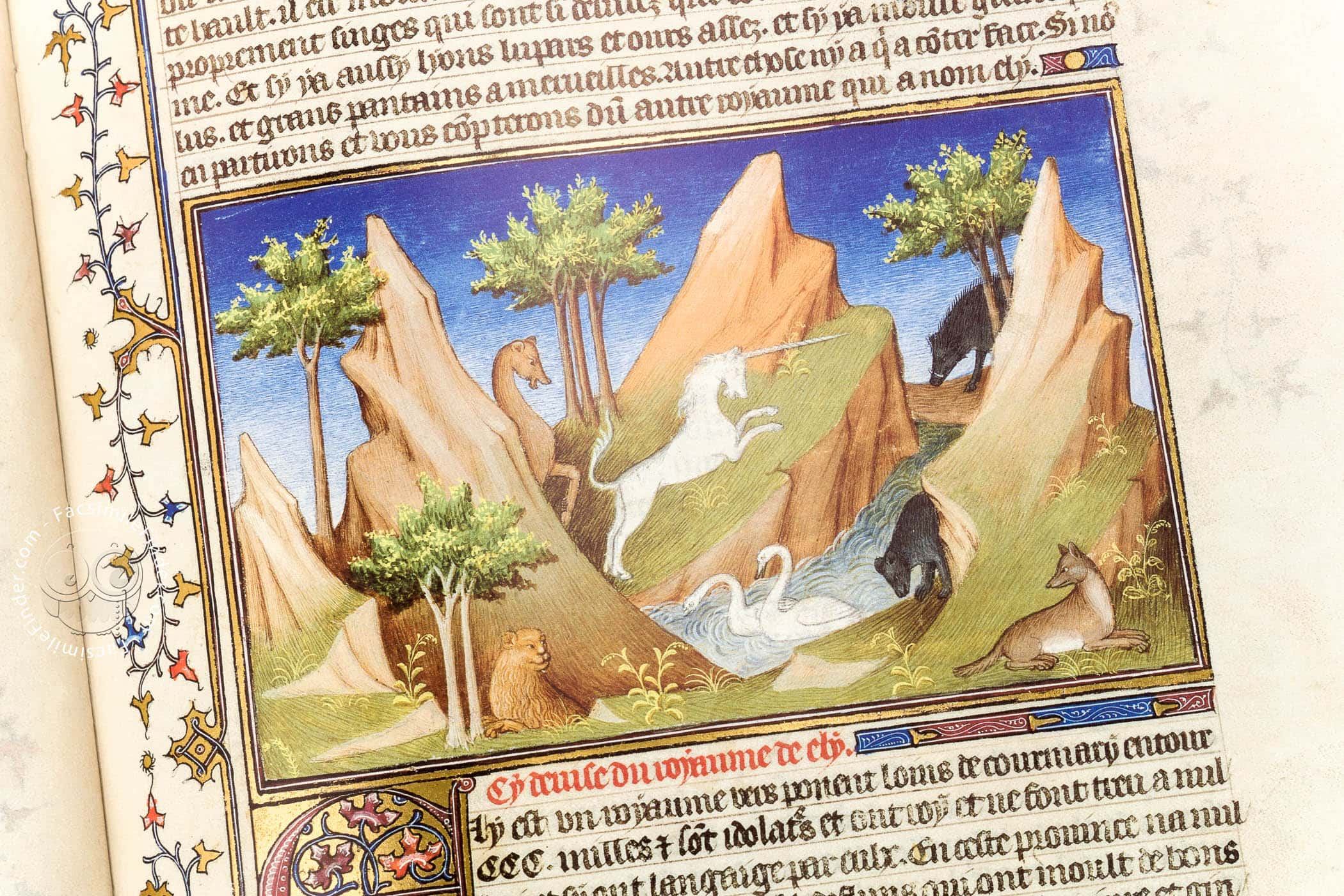

9. Animal or Myth?

Throughout his travels, Polo encountered many unusual animals that he often mistook for mythical creatures. He described crocodiles as huge "serpents" that could “swallow a man … at one time,” and he thought horned beasts such as the Asian rhinoceros were unicorns.

8. Time to Go!

Around 1292, the Polos volunteered to escort a Mongol princess to Persia, and aimed to head to Europe after. The Polos had been itching to go home. They didn't just miss their families; Kublai Khan was in his 80s, and they feared what the regime change upon his death would mean for foreigners.

7. The Journey Home

When the Polos left the Khan, they set out by sea with a group of several hundred passengers and sailors to Persia. The journey was a hazardous one, and all but 18 of the original passengers died from disease or from storms; all the Polos (and the princess) survived.

6. No Possibility of Return

Had Polo been entertaining any ideas about returning to Asia, the death of Kublai Kahn shut those dreams down. After the Khan's death, the Mongol empire went into decline, and tribal groups reclaimed the land along the Silk Road. As the land route to China became more dangerous, very few travellers had the nerve to attempt the journey.

Sources: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11

5. Strangers in Their Homeland

When the Polos returned to Venice, they weren’t exactly greeted with a welcoming party. After being gone for over two decades, the people in their hometown didn’t recognise them, and the travellers found speaking in their native tongue, Italian, difficult.

4. East Comes West

In addition to introducing paper money to the Western world, Polo also described several other Chinese innovations to the West. Polo brought coal, eyeglasses, and a variety of rare spices to Europe's attention.

3. It’s Not About Him

Polo never intended his book to be read as a memoir. He wanted it to be a description of the places that he and his family visited and what they saw there. Because of this, few personal details about his life are included.

2. Lasting Legacy

Polo’s chronicle of his adventures inspired the explorers who followed him. Christopher Columbus carried a copy of the book with him on his voyages, and had even planned to follow Polo’s route and make contact with the Kublai Khan’s successor. As in so many things, Columbus was in error here: the Mongol empire had fallen.

1. Fact or Fiction

For years, people thought that Marco Polo’s tales were almost entirely made up, and even though he said he was telling the truth for his entire life, on his deathbed he said “I did not tell half of what I saw,” indicating that perhaps there were even more marvels he found that remain unknown.