Few things changed human history more than the printing press. Thanks to the press, people could produce literature at unprecedented rates, spread their ideas to the masses, and communicate across vast distances. But the story of who invented printing isn’t straightforward. We’ll travel from China to Germany, traverse centuries of history, and explore a huge moment of technological revolution as we investigate the question of “Who Invented Printing?”

Who Invented Printing, And Why?

It can be hard for modern people to understand the way the printing press changed the world—but consider the alternative. Before the press, the only other option was to write by hand. Hand-written, or “manuscript,” books were often beautiful objects, but when it came to mass producing books, the process was incredibly slow and tedious. Monks would painstakingly write one copy, then repeat ad nauseum.

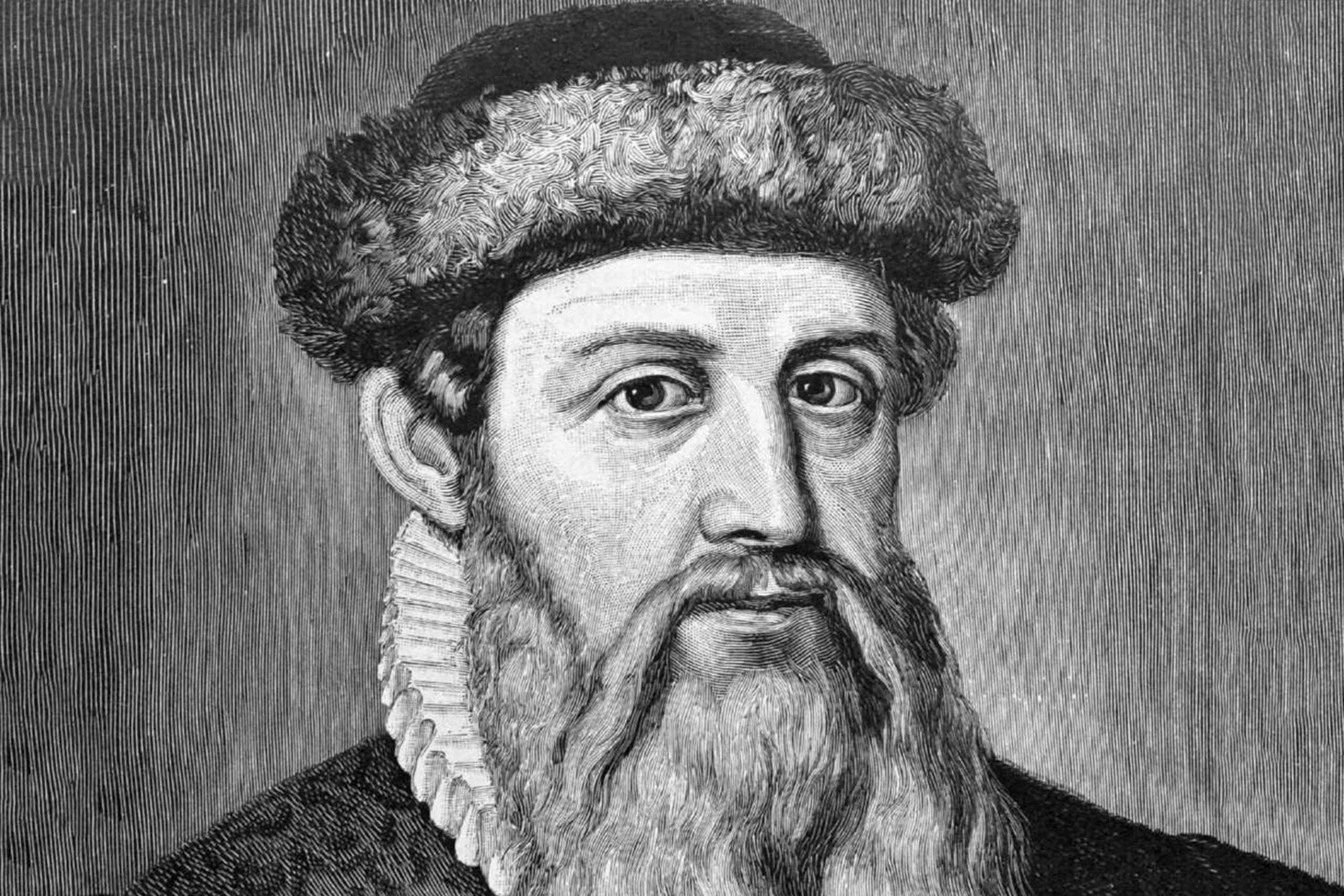

If you wanted a single copy, a monk was your man. But what if you wanted 10 copies? Or 100? Or 1,000? Suddenly, the monk’s timeline extends into eternity. This is where Johannes Gutenberg, an average everyday goldsmith, entered the arena in 1440 and revolutionized the way we print and disseminate the written (or I should say, printed) word. But to get to him, we have to back it up a bit.

Printing 101: A Field Trip to Ancient China

Even though everyone credits Gutenberg with inventing the printing press, it’s worth pointing out that the story is a little more complicated. In Asia, people had been printing with blocks (essentially old stamps) and wooden “setting squares” for centuries. Bi Sheng’s name should really be the one that we associate with printing, but because Western readers tend to prioritize Western history, that hasn't been the case.

You see, Bi Sheng decided to create thousands of tiny stamps, each carved with a unique Chinese symbol. By combining these delicate stamps in unique orders, Sheng could create endless documents about any topic he desired. Yet even though Sheng had just thought up one of the most important inventions in history, it seems like he was ahead of his time. His idea didn’t really catch on, mostly slumbering in the thrilling world of administrative documents and government registers. Instead, centuries later, Sheng’s brilliant invention would reach its potential in Europe.

Who Invented Printing? Gutenberg Enters the Arena

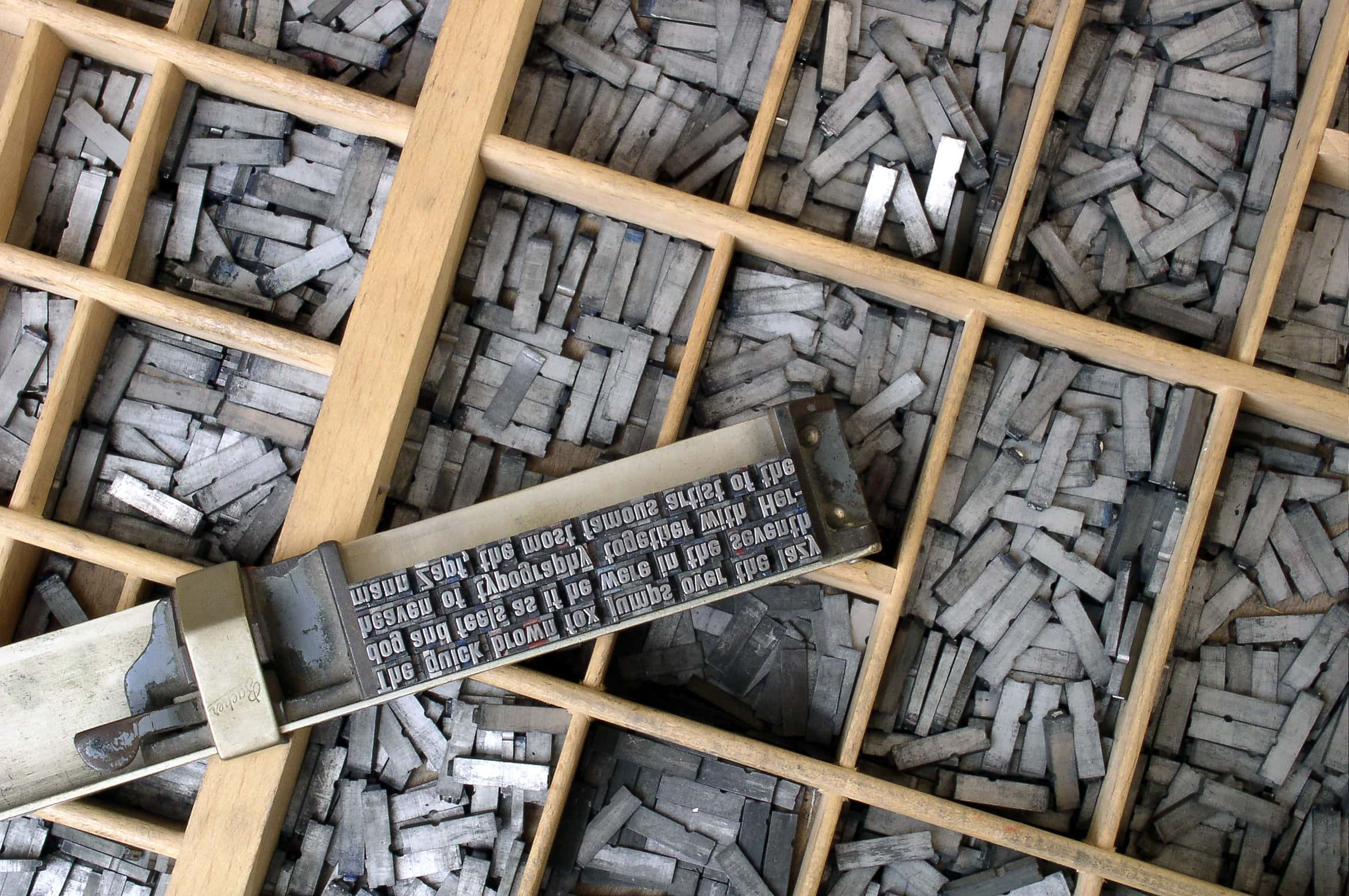

In 1440, the goldsmith Johannes Gutenberg got his own entry in the history books when he, consciously or unconsciously, drew on Sheng's invention and introduced moveable metal type. Gutenberg cast thousands of tiny metal blocks, each of which would imprint a specific letter—everything from A to Z, along with punctuation, spacing, and old characters like the long s.

This seems like a small difference from the woodblock technology of early China and even the woodblock presses available in Gutenberg's Germany, but his upgrade made the printing press more durable and much faster. The printing press literally “pressed” pieces of paper against the arrangements of the inked metal molds, kind of like an elaborate custom stamp.

Wikimedia Commons Johannes Gutenberg

Wikimedia Commons Johannes Gutenberg

When the workers released the press and saw the paper, it was now imprinted with a custom message. After many long days of type-setting and printing, a shop could produce a pamphlet or a book. And when the job was done, the type could be cleaned up and redistributed back into its proper compartments, where all those little As, Bs, Cs, and more would sit waiting for their next job.

But why did Gutenberg’s version of movable type spread so much faster than Sheng’s? The fact that the English alphabet only has 26 characters is key here. Because there are thousands of Chinese symbols, it took ages to produce enough square settings to adequately represent the language. English's discrete letters, meanwhile, made creating and casting our alphabet significantly easier.

From Manuscripts to Printing

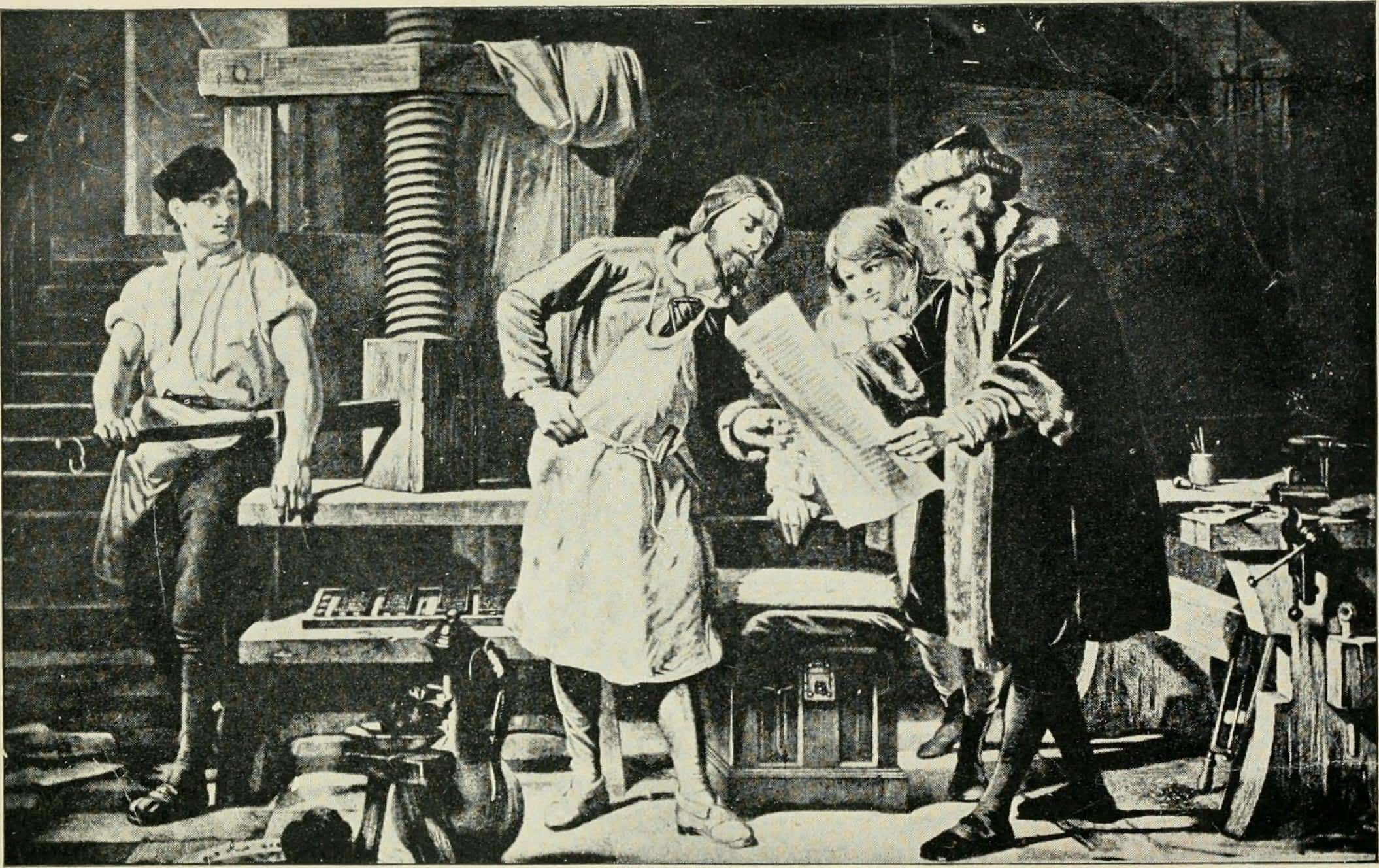

While monks had quite a low preparation time in that they could basically sit down and start writing, the printing press took a tremendous amount of foresight. People had to cast type, build the press, arrange the type, proofread, and more. But after that initial investment of time and money, a printer could theoretically produce limitless copies and not just recoup their investment, but also make a tidy profit.

The printing press was an enormous technological advancement and its popularity quickly spread. What began in 1440 in Germany rapidly moved across Western Europe. By 1500, this new batch of printing presses had created more than 20 million volumes. In the modern day, we call this period of time “The Printing Revolution.” But the revolution's biggest moment was yet to come...

Martin Luther: a Case Study

Martin Luther has gone down in history as the rebellious German priest who kick-started a reformation...but he did it with the printing press. In 1517, Luther nailed his so-called "Ninety-Five Theses"—a document that criticized the corruption of Roman Catholic doctrines—to the doors of Wittenberg churches. In order to spread the word, Luther had created multiple copies of his Theses on the relatively new-fangled printing press.

Thanks to these multiple copies of the fiery document, Wittenberg was soon buzzing with Luther's revolutionary ideas about the rot at the center of the Catholic church and the need to democratize faith away from the Pope. In the end, Luther reached an enormous amount of people and brought about a seismic change: The Protestant Reformation.

Wikimedia Commons Martin Luther

Wikimedia Commons Martin Luther

As the historian Colin Woodard argues, Luther’s Theses were the first “mass-media” event in the world. Indeed, they were a true indication of just how powerful the printing press could be. From there, things have only gotten bigger, faster, and better. We now have everything from established newspapers to trashy tabloids to classic novels—all because of Sheng, Gutenberg, and one angry priest.