Splitting The Atom

In the years following Thomson's discovery, we got a better and better understanding of the atom's behavior. Using mathematics and real-world experimentation, physicists studied these fundamental particles. They soon realized that the centuries-old idea of the "uncuttable" atom couldn't possibly be true.

Mass spectrometers allowed us to measure the mass of atoms, and things weren't adding up. The only way experimental data made sense was if atoms were made up of two kinds of particles: One positively charged, and one neutral. The charged particle became known as a proton, and in 1932, James Chadwick detected the neutron for the first time.

Scientists had finally done what alchemists had been trying to do for centuries: They changed one element to another. Sure, we hadn't quite turned iron into gold, but by firing charged particles at beryllium atoms, they managed to break the bonds of the nucleus, splitting proton from neutron for the first time, and creating trace amounts of entirely different elements. The uncuttable atom had been cut—but we still have deeper to go.

Factinate Video of the Day

History's most fascinating stories and darkest secrets, delivered to your inbox daily.

Pandora's Box

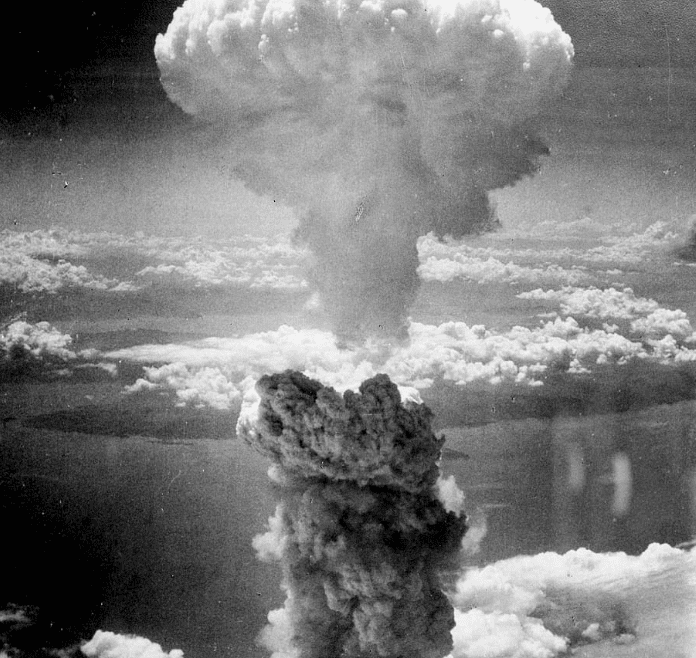

Unfortunately, the discovery of the neutron pointed scientists straight at a terrible discovery: The atomic bomb.

We'd discovered we could split an atom: nuclear fission. Even more, we discovered that the bonds holding atoms together contained a lot of energy. Experiments continued, and eventually, Leo Szilard learned that, if you broke just the right atom in just the right way, it could begin a chain reaction that would release an enormous amount of energy. He'd discovered the foundation of the nuclear bomb.

The United States dropped two on Japan, killing over two hundred thousand people, just 11 years later.

But we still haven't found the answer to "What is everything made of?" Democritus's beautifully simple atomos was inspired—but the truth, as always, ended up being much more complicated.

Now that we're going past the atom, we're really down in the muck. Thankfully, that muck has a nice and easy-to-grasp name: The Standard Model. But don't let the boring name fool you—it couldn't be more complex.

The End Of The Line

The Standard Model of particle physics is by far the best scientific theory that we've come up with to date. It divides everything—and I mean everything—into 17 fundamental particles and four fundamental interactions.

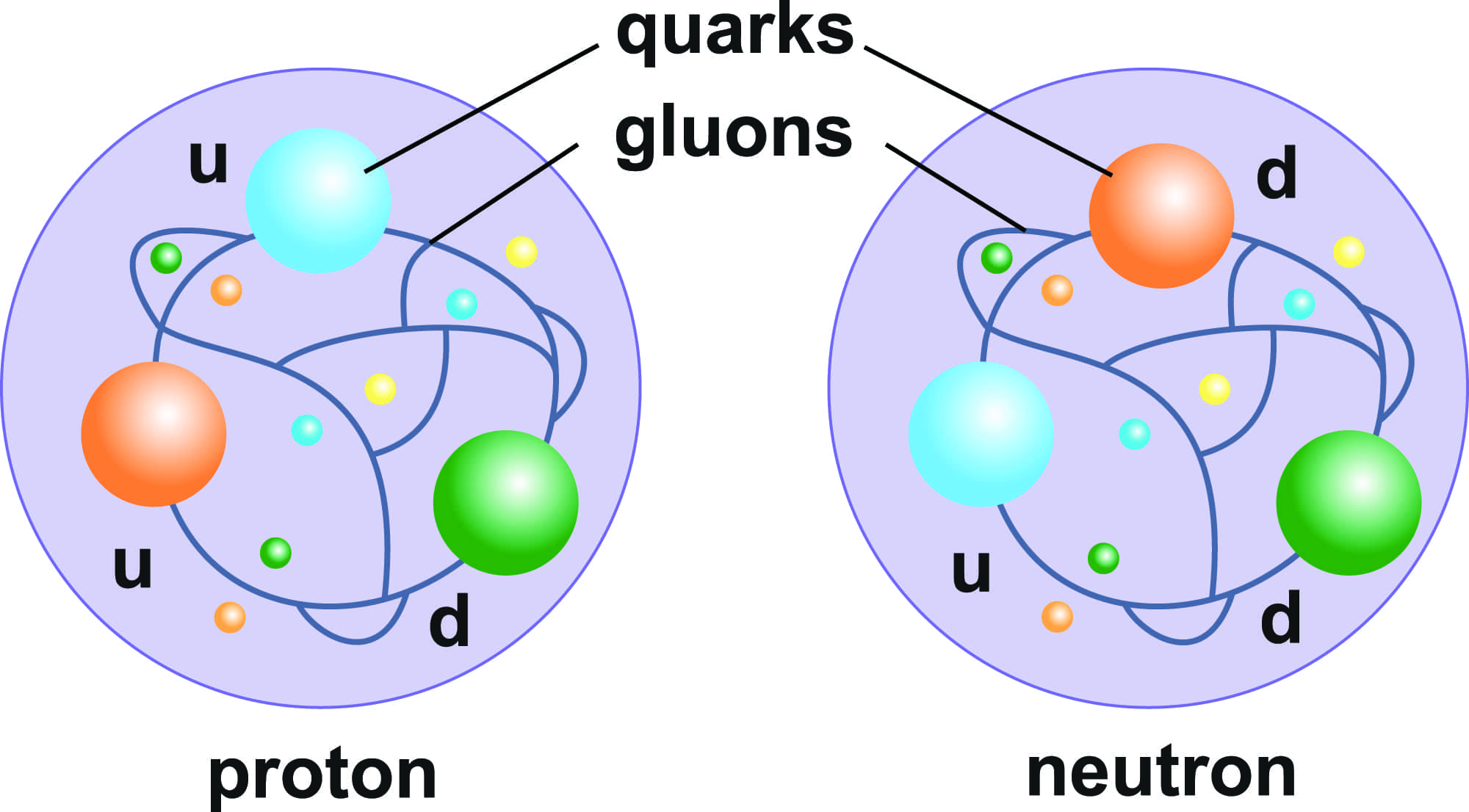

The Standard Model finally gets us to the end of the rabbit hole. It describes "quarks," which make up protons and neutrons, and the "gluons" that hold them together. It also describes...just about everything else. Electrons? Standard Model explains it. Light? Standard Model explains it. That fancy particle you may have heard of called the Higgs Boson? You guessed it.

No Easy Answers

When I first started my search for the answer to "What is everything?", I hoped for an easy answer just like Democritus. It would be wonderful if everything could be boiled down to something as simple as an atom. But when we go down this rabbit hole, only one thing is clear: Things could not be more complicated.

I can tell you that atoms are made up of quarks, that form neutrons and protons, that form atoms, that form molecules...that eventually turn into that sandwich we started with. Maybe it'll help you at bar trivia sometime. But it turns out the universe is way more complex than we like to think. We've reached the bottom of the rabbit hole, and it's a maze down here.

If you want to understand more, you'd better bone up on your mathematics, because you're going to need it. Or you, like me, can be happy with the bar trivia version.