When Alex Honnold climbed over El Capitan’s ledge on June 3, 2017, he did so quietly. While people in the rock climbing community were largely aware of Honnold’s dream of free soloing the greatest cliff in the world, he didn’t exactly spread the word that he was trying.

It wasn’t until the movie Free Solo came out that the world’s eyes finally turned to Yosemite and El Capitan. But while Honnold’s ascent is one of the most amazing human achievements ever, one of those hyperbolic moments that can only be adequately described with the most sensational language, the history of climbing El Capitan is actually filled with such moments.

For hundreds of years, the surreal monoliths of Yosemite Valley have inspired people to test their limits. Honnold’s ascent is probably the pinnacle of such adventures, but he could never have done it if not for the similarly-mad men and women who came before him.

In the Valley of Giants

People have been trying to get on top of Yosemite’s massive formations for centuries. Most sane adventurers probably hiked around the back, but the current wave of rock climbers aren’t the first to try and take a more direct route. In 1869, the famous naturalist John Muir climbed the Cathedral Peak with no ropes, just scrambling on his hands and feet.

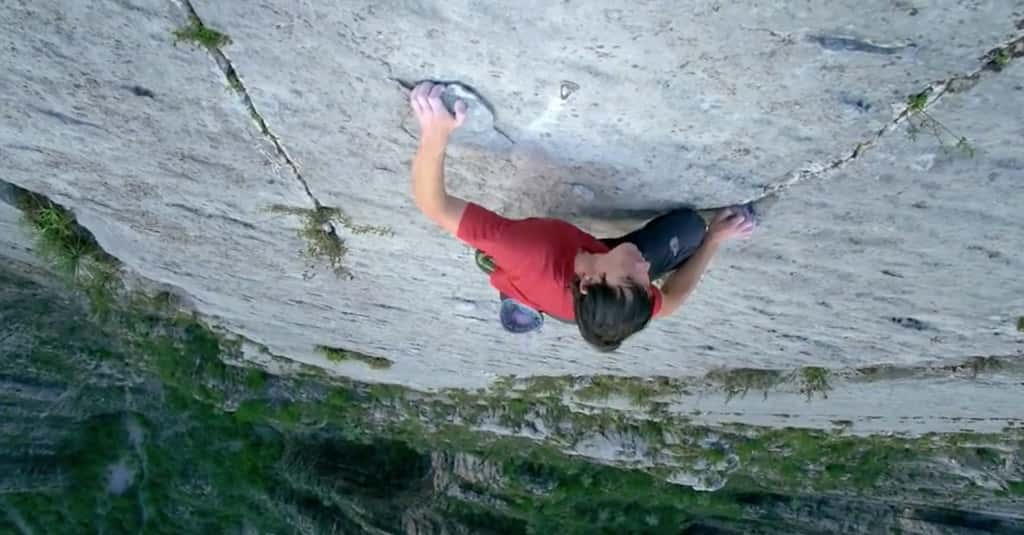

Alex Honnold - El Sendero Luminoso, Flickr Alex Honnold

Alex Honnold - El Sendero Luminoso, Flickr Alex Honnold

As the years went by, people started finding ways up Yosemite’s more sheer faces—but the early ascents in the Valley were a far cry from Honnold’s minimalist ascent. In those days, simply getting to the top of any of Yosemite’s obstacles was a near-impossible feat, and climbers did so by any means necessary.

At Any Cost

The first people to try and climb in Yosemite probably looked more like construction workers than rock climbers. They brought loads and loads of gear with them, and they would hammer their metal pitons into the rock and use them to help ascend further. It wasn’t the most elegant solution, and such practices caused irreparable damage to Yosemite's rock, but such "siege tactics" were involved in all of the valley's early ascents.

Mountain Home Air Force Base El Capitan

Mountain Home Air Force Base El Capitan

Through the 1930s and 40s, climbers managed to summit many of Yosemite’s massive rock faces, but the two most obvious prizes, the formidable Half Dome and El Capitan, lay unclimbed. Technology was getting better, these two cliffs were daunting, and no one had yet dared to challenge them.

Until the 1950s, when Warren Harding and Royal Robbins came along.

Rock Rivals

Harding and Robbins were two very different rock climbers. Robbins was more athletic, and he preferred to use the natural features of the rock as much as possible on his ascents. Harding didn’t care at all. He threw up as many bolts as he felt like on the wall. He just wanted to get to the top, and he did so by any means necessary.

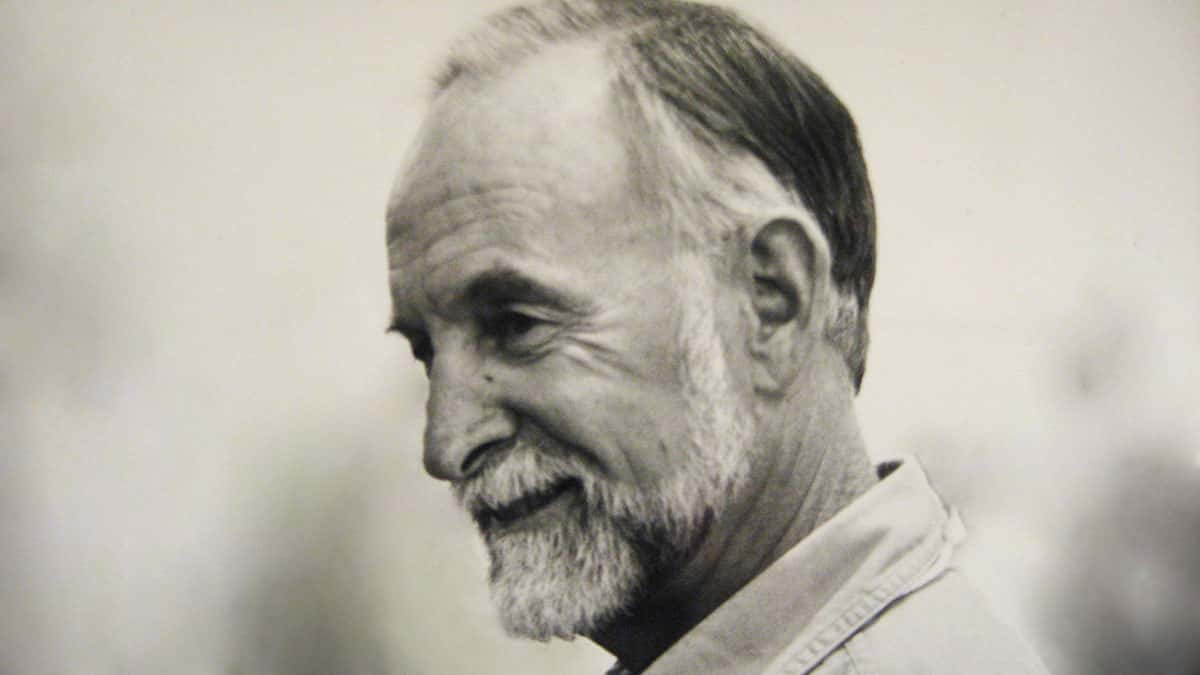

Wikimedia Commons Royal Robbins

Wikimedia Commons Royal Robbins

The pair of them set about climbing the slightly-less intimidating Half Dome first. In 1957, Harding planned his ascent and drove out to Yosemite—only to find Robbins already on the face. Harding was too late, and after a grueling five-day ascent, Robbins and his friend Jerry Gallwaas made it to Half Dome’s summit.

Score one for Robbins.

The Greatest Prize

But of course, while Half Dome is one of Yosemite’s greatest features, it’s not the greatest. That honor has always gone El Capitan.

Harding wasn’t about to let Yosemite’s greatest prize slip through his fingers—but this was uncharted territory. El Capitan is one of the largest rock faces on earth. No one had ever tried conquering such an obstacle. He and a group of friends started their challenge by studying the cliff and determining a route that might be possible.

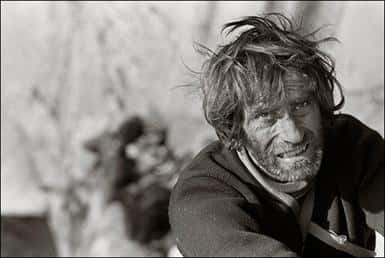

Wikimedia Commons Warren Harding

Wikimedia Commons Warren Harding

But no matter how many hours they spent staring at El Cap's face from the ground, they knew there was only one way to see if an ascent could be done. Soon enough, it came time to start trying.

Dangling Off the Edge of the Earth

It’s hard to adequately express just how insane the first attempts at climbing El Capitan were. As John Long, a legendary climber and one of the first men to climb El Cap in a single day put it: “It’s just scary as hell up there, man. You’re with—you’re talking about way up, thousands of feet off the ground—with just...the gnarliest, least effective gear you could ever imagine. I mean, really, just winging it up there.”

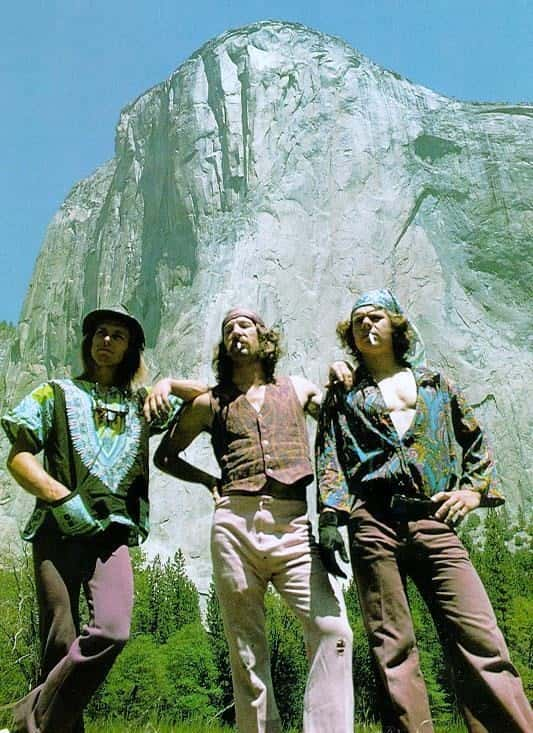

Wikimedia Commons Billy Westbay, Jim Bridwell, and John Long after the first one-day ascent of the Nose in 1975.

Wikimedia Commons Billy Westbay, Jim Bridwell, and John Long after the first one-day ascent of the Nose in 1975.

While today, any climber conquering even the simplest cliff would have a harness, climbing shoes, a modern safety device, and a climbing-specific rope, Harding and the men with him had no such luxury. When they began their attempts on El Cap, they simply hung from their waist. Not only was this, at best, extremely painful in the event of a fall, but it also made lugging the hundreds of pounds of gear necessary ludicrously difficult.

They wore leather shoes and had no access to modern, safe belay devices or ropes. Anyone looking at their gear today would probably run screaming from a face like El Capitan. Not Harding.

Look Ye Mighty

Time and time again, Warren Harding through himself at El Capitan, and time and time again, the face spit him off. Even with their hammers and pitons, the summit eluded them. But Harding could not be deterred. By the time he crested the top, he had spent a total of 45 days on El Capitan’s face, over the course of 18 months.

Wikimedia Commons El Capitan in Yosemite National Park viewed from the Valley Floor.

Wikimedia Commons El Capitan in Yosemite National Park viewed from the Valley Floor.

He had done it. He had walked up to the base of Yosemite’s greatest challenge and scaled the entire face, proving the impossible to be possible. But while others may have felt triumphant in such a moment, Harding was humbled:

“As I hammered in the last bolt and staggered over the rim, it was not...clear to me who was conqueror and who was conquered: I do recall that El Cap seemed to be in much better condition than I was.”

Free

Of course, while he was the first to climb El Capitan, Harding was hardly the last. His rival, Royal Robbins, wasn’t deterred by losing the race. Not long after, he managed to climb a different route up El Capitan using very limited hardware, proving that El Cap could be climbed without Harding’s inelegant siege tactics.

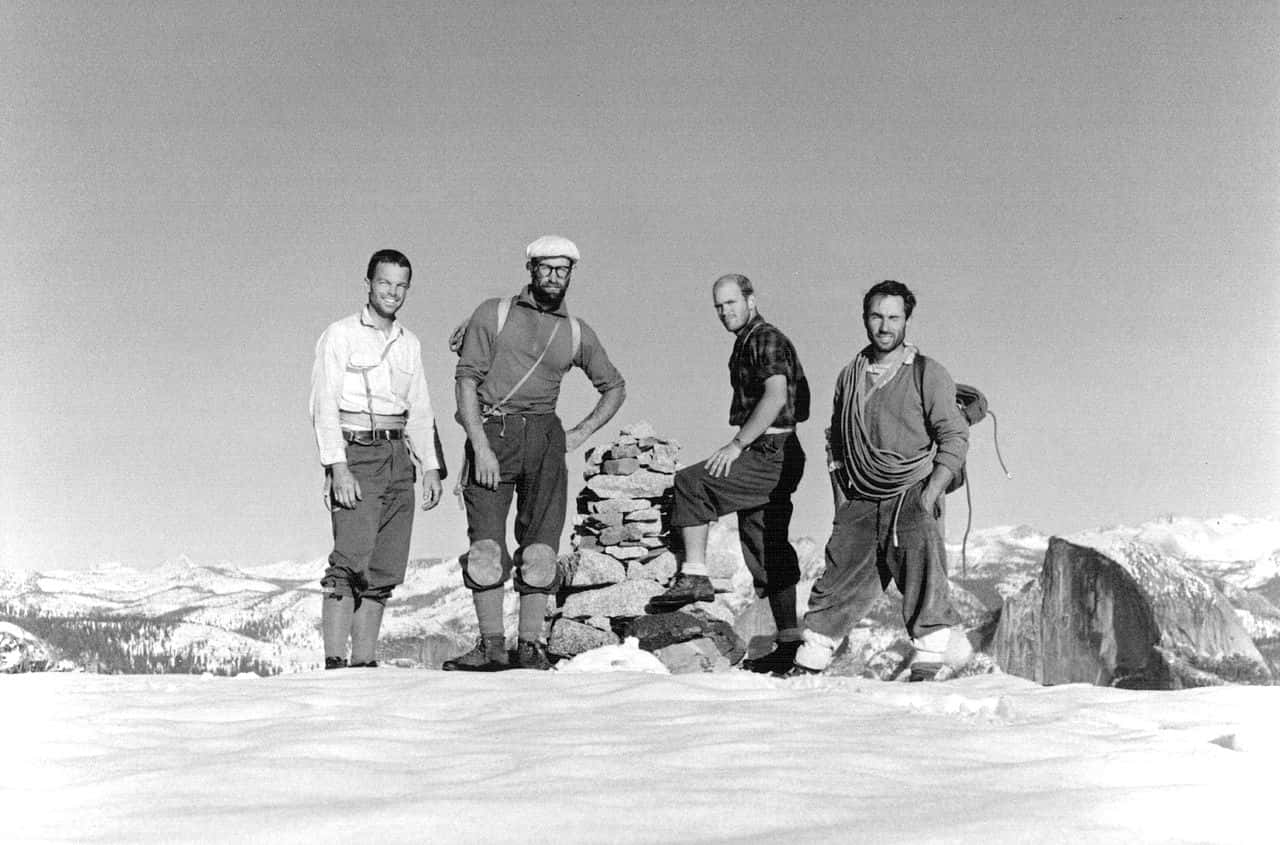

Wikimedia Commons Tom Frost, Royal Robbins, Chuck Pratt and Yvon Chouinard on the summit of El Capitan on 30 October 1964, following the ten day ascent of the North America Wall, Yosemite National Park, California.

Wikimedia Commons Tom Frost, Royal Robbins, Chuck Pratt and Yvon Chouinard on the summit of El Capitan on 30 October 1964, following the ten day ascent of the North America Wall, Yosemite National Park, California.

Over the decades, pitons and other aid-climbing techniques fell out of favor, and in the 1980s, Lynn Hill finally did what no one before her could ever manage: She was the first person ever to free climb El Capitan, using only the rock to help her. Fittingly, she managed the feat on the Nose, the same route that Harding first climbed decades before.

A New Dawn

After Hill proved that El Capitan could be climbed without the help of pitons, bolts, and fixed ropes, more and more free-routes were established on the cliff. Her ascent paved the way for people such as Tommy Caldwell and Kevin Jorgeson, who in 2015 climbed El Capitan’s Dawn Wall, widely considered to be the hardest big-wall climb in the world.

Wikimedia Commons Lynn Hill videoing a climber

Wikimedia Commons Lynn Hill videoing a climber

And of course, we’re brought full circle to June 3, 2017, when Alex Honnold completed his free solo. What took Warren Harding 45 days and untold amounts of gear took Honnold a mere three hours and 56 minutes, armed with nothing but his shoes and a chalk bag.

El Capitan

But while Honnold’s ascent is undeniably one of the most remarkable feats of physical and mental endurance ever, at least he knew what lay before him. He'd personally summited El Capitan countless times. He knew the route he was climbing like the back of his hand.

Warren Harding - Recollections: The Wall of the Early Morning Light, Tuffrock Media Warren Harding

Warren Harding - Recollections: The Wall of the Early Morning Light, Tuffrock Media Warren Harding

Harding and the men who climbed with him charged up El Capitan with no idea what lay ahead of them. They used gear that would hardly be considered fit to climb a staircase today. And when they made it to the top, they laid the groundwork for Hill, Caldwell, Jorgeson, Honnold—and for whoever gives El Capitan the next page in its history.