Coming off of 2018, Our Year of the Scammer, it’s not easy being a member of the discerning public. Frauds like Fyre Festival have turned modern consumers into hardened skeptics, but they’ve also made us nostalgic for a bygone age where we didn’t have to be so guarded, where the deluge of online information was a mere analog stream, and where the voices coming from our radios and TV sets were reliable.

At the center of this quiet, idyllic vision of the past is Orson Welles’ infamous 1938 radio broadcast of The War of the Worlds, where panicked listeners, the story goes, became genuinely concerned extra-terrestrials were attacking Earth. How quaint and trusting! Can you actually believe people tuned in to a radio program and thought alien invasion was imminent?

Well, they didn’t.

In fact, the hysteria around Welles’s broadcast has been debunked for some years; historians like Robert E. Bartholomew and Frank Stanton have long argued that the media greatly exaggerated the mass panic. Nonetheless, we continue to believe that in a world before social media, some bumpkins once thought a radio show was the apocalypse. In short, radio audiences weren’t being scammed—we were.

After the shock, anger, and maybe shame of this revelation wears off, at least one important question remains: what makes the story so believable, and so compelling? Well, the answer speaks more truth about ourselves than any scam has a right to. What’s more, as with every good lie, some parts of the eerie tale are true.

Getty Images Orson Welles

Getty Images Orson Welles

Fool Me Once

At 8 pm on Sunday, October 30, 1938, one day before Halloween, Orson Welles presented his CBS radio adaptation of the H.G. Wells’ classic novel The War of the Worlds. But where the original takes place throughout Great Britain, Welles set his broadcast in America. Being unsponsored, the show took infrequent commercial breaks, and set itself up as a bulletin-style newscast interrupted by breaking news of an alien invasion.

It was a perfect storm for misunderstanding: popular history claims people tuning in from other shows didn’t hear the introduction to the program, and didn’t have any commercial breaks to tell them that the broadcast was fictional. And don’t forget that in 1938, tensions were rising in Europe, and people were primed for war. The panic was reportedly swift and powerful: though only a subset of people believed aliens were attacking America, others found it quite plausible that humanity had initiated its own war.

The rumblings started early at CBS studios. According to one of the show’s producers, at 8:32 pm, supervisor Davidson Taylor got a phone call. He came back from the conversation "pale as death," with orders to interrupt the program and confirm it was fictional. Unfortunately, as the show was about to take its first break, this never happened.

As the hour-long program went on, more signs of tension appeared. One of the voice actors remembered finishing his part and then sitting and watching policemen slowly trickle in—until they had suddenly filled up the studio. The phone rang again: a mayor of a Midwestern town claimed the broadcast had incited mobs. Then, as producer John Houseman recalled, as soon as they got off the air, “the studio door…burst open.” What followed was like a scene from a movie.

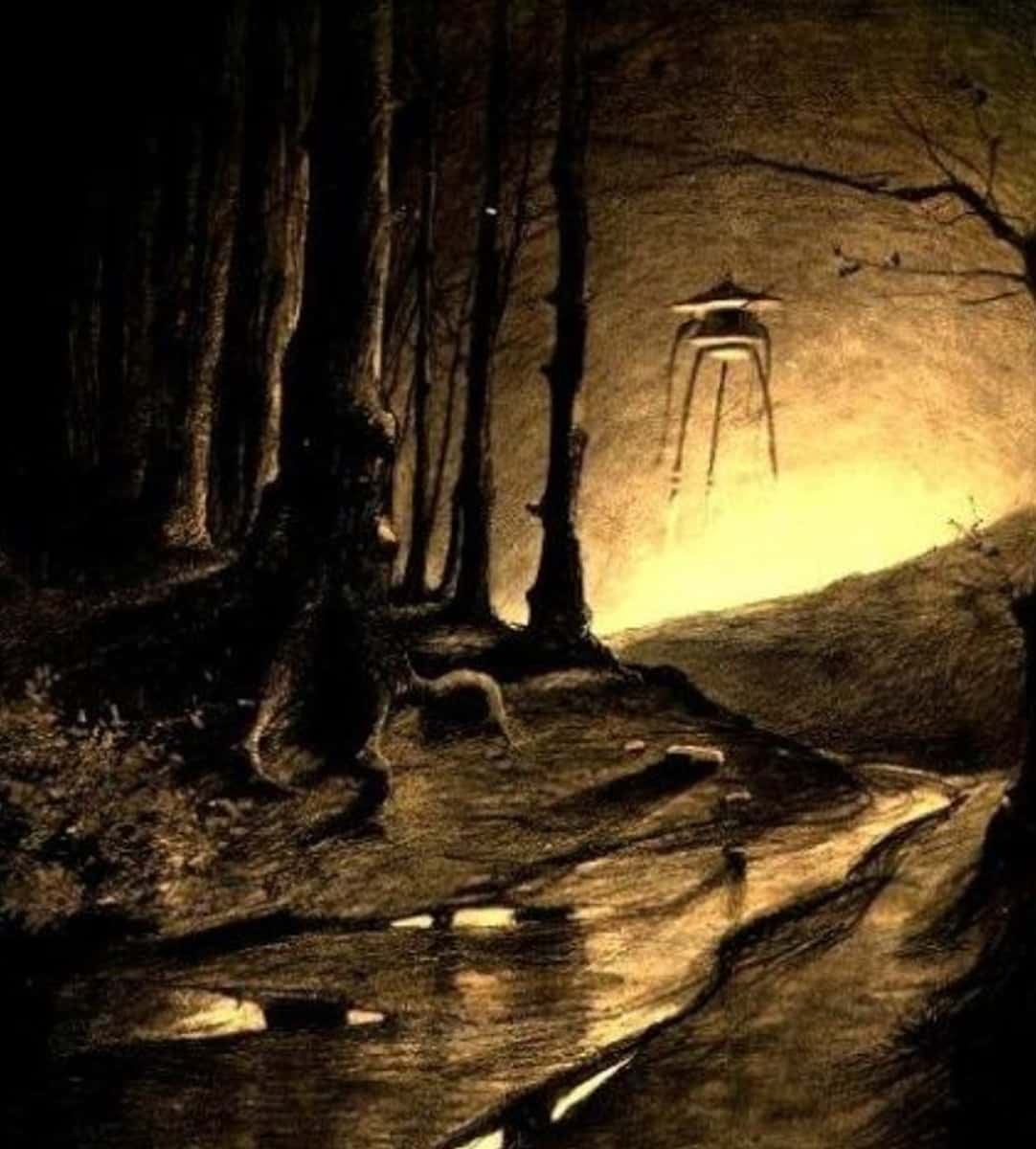

Wikimedia Commons Illustration by Alvim Corréa, from the 1906 French edition of H.G. Wells' "War of the Worlds".

Wikimedia Commons Illustration by Alvim Corréa, from the 1906 French edition of H.G. Wells' "War of the Worlds".

Police and press alike started questioning CBS personnel about the mass hysteria, accidental deaths, and general uproar the broadcast had apparently caused, all while their executives and employees were safely ensconced in their innocent studio. Phone lines lit up for hours, scripts were scorched or salvaged, and in the middle of it all, Orson Welles sat hunched over, defeated and dejected. “I’m through,” he groaned, “washed up.”

But nothing could have been further from the truth.

Sign up to our newsletter.

History’s most fascinating stories and darkest secrets, delivered to your inbox daily. Making distraction rewarding since 2017.

Fool Me Twice

That fateful Halloween Eve ended up being the cornerstone of Welles’s career. Far from being blacklisted for his role in the scandal, he shot to stardom as a dramatist. And how much of a scandal was it, really? To be sure, panic had ensued—just much less than was reported. Modern research suggests most people were in the know, and that even panicked citizens were quickly calmed.

The aftermath of the event reveals that even Welles had some doubts about the controversy. As he said, “It wasn't long after the initial shock that whatever public panic and outrage there was vanished. But, the newspapers for days continued to feign fury.” Indeed, many historians argue that print publications, perhaps eager to discredit the newfangled medium of radio, gleefully exaggerated, and continued to exploit, the rather subdued events of October 30, 1938.

Of course, they also had some help from Welles himself.

Wikimedia Commons Illustration by Alvim Corréa, from the 1906 French edition of H.G. Wells' "War of the Worlds".

Wikimedia Commons Illustration by Alvim Corréa, from the 1906 French edition of H.G. Wells' "War of the Worlds".

Though he initially confessed skepticism about the hype, Welles quickly incorporated the hysteria into his brand. Years later, he described that night to director Peter Bogdanovich with characteristic flair: "Houses were emptying, churches were filling up; from Nashville to Minneapolis there was wailing in the streets and the rending of garments.” Since 1938, CBS has also promoted multiple TV spots and series relating to that fateful night.

And we lap it up, allowing mundane reality to become personal myth. But once more: why?

True Lies

This is a complex question to answer. Researchers Jefferson Pooley and Michael Socolow argue that the War of the Worlds panic tale persists because it illustrates our own anxieties about media and its intrusion in our lives. This is true, but it’s only half the story: we are also fascinated by the heightened reality media provides. Welles once acknowledged this fascination—and pleasure—when it came to War of the Worlds, comparing the hoopla to “the same kind of excitement that we extract from a practical joke in which somebody puts a sheet over his head and says 'Boo!' I don't think anybody believes that that individual is a ghost, but we do scream and yell and rush down the hall.”

Wikimedia Commons Detail from the trailer for The War of the Worlds (1953)

Wikimedia Commons Detail from the trailer for The War of the Worlds (1953)

This same kind of excitement continues today, in our own media. Modern reality shows like Survivor, Jersey Shore, The Bachelor, and countless others provide dramatic plots through the frame of authenticity—and just like Welles’s audience, we watch them eagerly, not really believing in them, but happy to be fooled all the same. Many times, these programs reflect or address a contemporary issue, sewing themselves back into the fabric of our reality, just as with the radio drama and the impending World War II. Both the broadcast and its myth provide the same pleasure: a story just close enough to reality to be believed.

For all that we like to think of today’s audiences as irony-laden sceptics, we have to face the cold, hard truth. We may try to divorce ourselves from the “gullible” listeners of War of the Worlds, but their experience is our inheritance.