Like many economic bubbles—from Bitcoin to the South Sea bubble—Holland’s infamous “Tulip Mania” was doomed to burst. But the whole story of its fever pitch and reportedly ruinous fall is so much more complex than we imagine.

It’s All the Rage

Every so often, a craze sweeps through a nation, grips us like a tight fist, and then fades into obscurity as suddenly as it appeared. Today we have Bitcoin; in the 1990s there were Pokemon cards and Beanie Babies; and the Victorian age was marked by manias for everything from ferns to orchids. Yet the 19th century was far from the first time that we became obsessed with botanical luxuries, and 17th-century Holland is now infamous for the rise and fall of its so-called “tulip mania.”

During this craze, tulips were status symbols of both immense wealth and immaculate taste. Turkey cultivated tulips since the 11th century, and in the 15th century Sultan Mehmed II featured the highly-prized flowers in his spectacular royal gardens in Istanbul. When Holland became a merchant powerhouse around the Dutch Golden Age, tulips then made their way over to the country via the bustling port cities of Amsterdam, Haarlem, and Delft.

The emerging capitalist economy of the Netherlands, hungry for the next big thing, eagerly accepted the vibrant flowers. Tulip bulbs grown from seeds can take a whopping 7-12 years to develop, but established bulbs will flower within 12 months, making them an attractive commodity. Even so, the tulip also has an alluring scarcity. Tulips only bloom for about one week in an entire year, heralding the warm days of summer—and representing a perfect luxury item for the discerning Dutchman: rare, fleeting, and beautiful.

For a brief moment, the tulip had its day. Then trouble started brewing.

Future History

The craze reached such heights that soon mere tulip bulbs, not even the flowers themselves, were bought and sold for exorbitant prices in the hopes that they might bloom. Some people exchanged whole salaries for one bulb, and an apocryphal story even tells of a sailor who mistook a pricy bulb for a humble onion and ate it for breakfast, sending an entire family into ruin. (For what it's worth, tulip bulbs can be poisonous and taste awful at the best of times.)

This focus on tulip bulbs, not flowers, created something fascinating, terrifying, and mostly unknown in Europe up to that point: a futures bubble. By selling the bulbs, merchants and buyers were betting on the future of the tulip, which is always a risky venture. To make matters more precarious, the mania then drove up the bulb’s worth to astronomical, unsustainable prices, forcing this gamble to accrue incredibly high stakes.

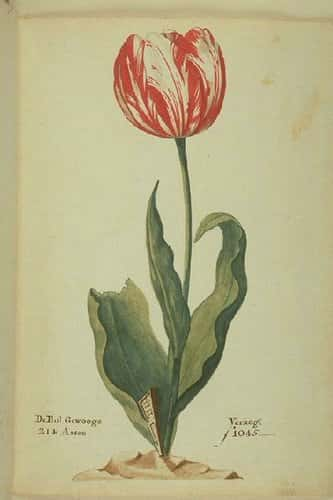

It didn’t help that the Dutch treated the tulips like winning racehorses. Designer growers called certain varieties by appropriately magnificent names like the Admiral, the General, Scipio, and even Alexander the Great. Groups of tulips soon became stratified: solid-colored Couleren tulips were less valued and workaday, while Rosen tulips (red or pink with white streaks) and Violetten tulips (purple with white streaks) were highly sought-after. Yet nothing beat the Bizarden—red, purple, or brown tulips that were flecked with yellow striping. This was the rarest and most valuable tulip of all, and it fetched more than a pretty penny.

Ironically, the magnificent Rosens, Violettens, and Bizardens hid a dark secret. Their cherished tulip streaks were actually the result of a viral infection from the “mosaic” or “tulip breaking” virus. Though the virus “breaks” or stripes the tulip petal in an aesthetically pleasing way, it also makes the bulbs unstable and difficult to grow.

Of course, the Dutch didn’t know about the virus, so instead of turning buyers off of an unreliable product, the difficulty of finding and growing striped tulips only increased their value. Prices continued to skyrocket—but pride comes before the fall.

Black February

By November 1636, the appetite for tulips was so large that even regular, non-streaked bulbs were worth whole salaries. A formal futures market also started in earnest, with traders buying and selling contracts for the next seasons' bulbs. It was not, however, anything like a scene from Wall Street. These traders met in small taverns and paid a measly few Dutch guilders to lay claim to a futures contract. They exchanged no bulbs, called the nominal fee “wine money,” and operated on an idyllic, independent honor system that took place outside the official Dutch Exchange.

Soon, bulbs were switching hands as many as 10 times a day, people were speculating wildly on tulips they’d never seen, and merchants were putting up massive sums of money. Then, in February 1637, it ended with bang. One day, buyers failed to show up to a bulb auction in Haarlem, dropping out the bottom of the tulip trade and setting off a chain reaction. The bubble burst, collapsing the tulip prices and erasing all of tulip mania practically overnight.

This much we know—but then things get hazy. Many sources report the utter, sudden ruin of a huge swath of Dutch merchants in the fallout. However, two groups likely exaggerated these reports: Dutch Calvinists who wanted to emphasize the decadence of capitalism, and modern-day researchers looking for a historical parallel to our own economic follies.

The truth is that most historians can find no evidence for any widespread collapse of the Dutch economy after the bubble burst—and some, though fewer, even debate whether it was a true bubble at all. Nonetheless, Although Tulip Mania did not have an outsized effect, it does leave behind enormous lessons for modern readers.

The End of an Era

If the tulip collapse didn’t ruin merchants financially, it devastated them in other ways. As mentioned above, merchants once conducted informal trade meetings and were happy to seal these deals with a wine fee, a handshake, and simple faith in another person. In a post-mania Holland, this was no longer possible. Buyers had refused to do the honorable thing and keep to their futures contracts, and now merchants couldn’t possibly trust one another.

Thus, in one fell “pop,” the excitement of early capitalism was lost, and a new age of capitalism set in; one where it was every businessman for himself. This is a loss that we are still feeling centuries later: The 17th century's newfound cynicism has echoes in the bad-faith business deals of the subprime mortgage crisis, the paranoia around Bitcoin, and the ruthless reputation of modern-day late capitalism.

In short, the fallout of tulip mania is still visible and still important; it has just taken on a different form.

Bring Me Dead Flowers

Nowadays, many of Amsterdam’s most magnificent, showy varieties of tulips have all but died out, and we can only imagine the glories that flowers like the “General of Generals” might have bestowed upon us. Though, maybe it wasn’t all that glorious anyway—just like the true history of Tulip Mania, perhaps our imaginations will always exaggerate and dramatize what we can’t know.

Only, this is also true of the tulip futures market as a whole: an entire, trusting trade devoted to imagining the wildest possibilities from the smallest things. Like the tulip, that trust in trade was a rare, fleeting, and beautiful thing that has since gone fallow, but that we might re-cultivate.