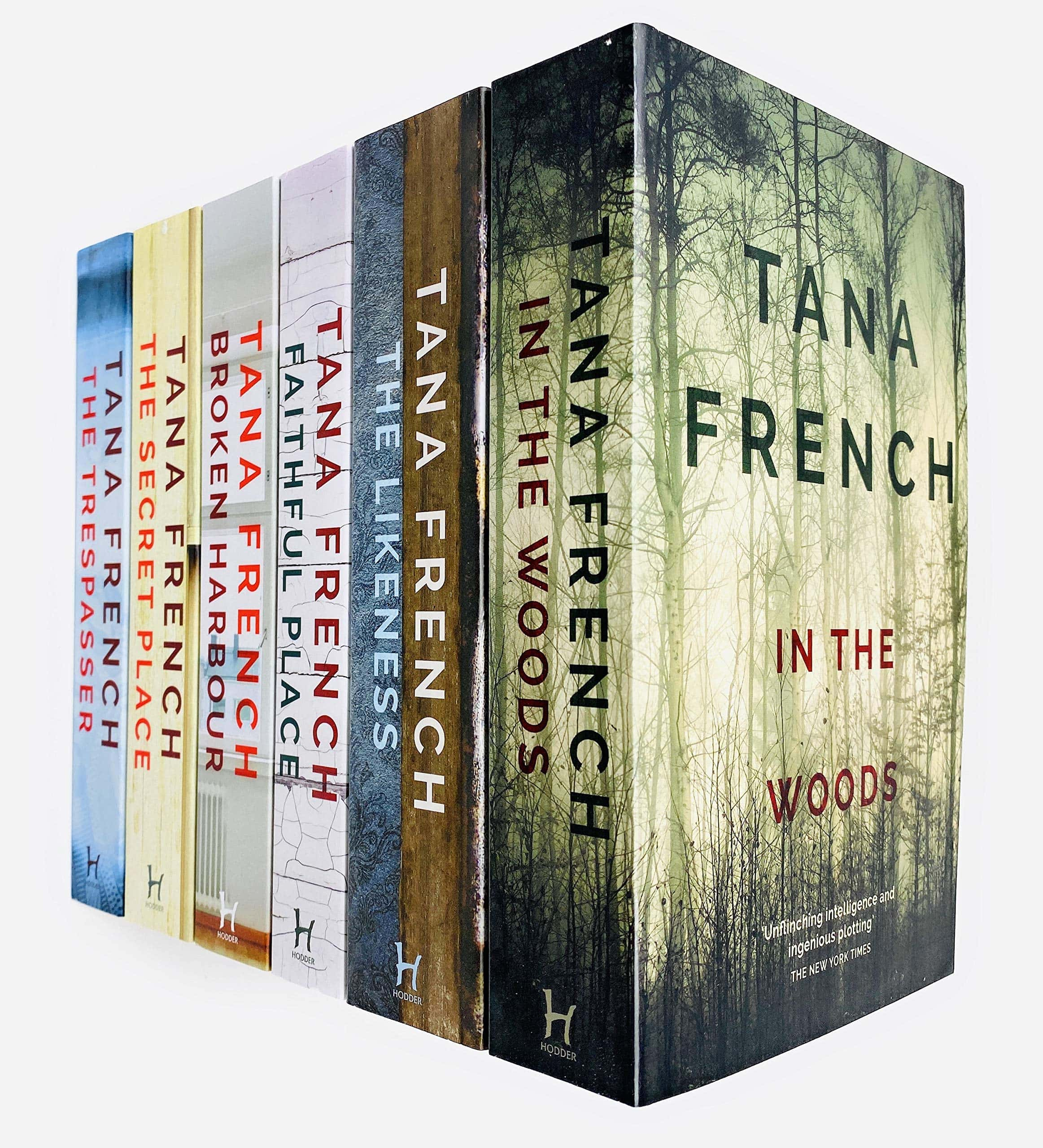

Few writers enjoy such a celebrated debut as Tana French. Her runaway bestseller In the Woods swept the literary establishment, earning rave reviews from high-profile publications like The New Yorker and Publishers Weekly. The sophomore curse didn’t strike her either. Starz recently adapted her popular follow-up The Likeness into a glossy TV series. In 2018, French’s writing idol Steven King lavished praise on her most recent novel The Witch Elm. In sum, French is called “The Queen of Irish Crime Fiction” for a reason—but what exactly separates her from her contemporaries?

French’s stories give us nuanced, helpful ways to re-envision our idea of criminality by exploring the roots of violence. In French’s oeuvre, crimes don’t only come from individual perversion or psychological derangement, but the way that a vulnerable person fits into their broader society. As critic Laura Miller writes, “all crime novels are social novels”—but few explore their societies as unblinkingly and with as much complexity as French’s works.

Broken Harbour: The Pride

Warning: This review contains major spoilers for all of French’s novels, but especially Broken Harbour.

French sets her novels in post-recession Dublin, a city traumatized by its ravaged economy. My favorite of her works, Broken Harbour, takes place at a halted housing development. When the picture-perfect Spain family is obliterated by a brutal act of violence—the wife Jenny survives by sheer chance—the resulting investigation acts as an object lesson in French’s manifesto about the way we think about crime.

The initial suspect is the wife’s childhood friend turned creepy stalker, Conor. Did the dissolution of their bond lead him to lose it and wipe out Jenny’s family in a fit of rage? In another novel, this would make for a fine ending. But in French’s Dublin, this is the comforting solution. In reality, things are much more complicated and the blame is much harder to pinpoint.

It turns out that the Spains had emptied their savings to enter the housing market. They bought a home in “Brianstown” (a promising seaside development), only for the recession to hit. With the Irish economy in tatters, the development grinds to a halt, and the Spains are left in the dust. What should have been their nest egg becomes worthless overnight. They can’t afford to sell, so they stay in the ghost town, isolated from their friends and family. Soon, bad turns to worse.

Factinate Video of the Day

Broken Harbour: The Fall

When the father Pat loses his job, the family expects that he’ll find another position—they’re wrong. By the time Jenny and Pat realize that they need to cut back on their spending, they’re already massively in debt. Even worse, Pat can’t cope with his redundancy and begins obsessing over an animal in the house’s rafters. Unfortunately for him, he’s the only one who can hear the supposed animal.

Jenny spends 100 harrowing days trying to cope with her increasingly deranged husband and providing stability for her two children. But after enough time passes and nothing improves, Jenny snaps. She kills her children and her husband, then attempts to kill herself.

The novel’s denouement sees a career cop, our narrator Scorcher Kennedy, grapple with the ambiguous case. Kennedy’s partner Richie wants to pin the murder on the dead husband, allowing Jenny to walk free and finish what she started, i.e., end her own life. For Richie, forcing Jenny to rot in a jail cell may be legal, but it’s not just. Kennedy is torn, but ultimately disagrees. He hatches a plan with Jenny’s sister to have Jenny plead guilty then recover in a psychiatric hospital. In the book’s final pages, readers must consider the case for themselves. French gives us no clear idea about whether justice has truly been served.

French’s Manifesto

In Broken Harbour, our narrator Scorcher Kennedy primes the reader’s interpretation of events. Scorcher vehemently believes that crime doesn’t just happen to people; in his words, “99 times out of 100, it doesn’t break into people’s lives. It gets there because they open the door and invite it in.” If anyone believes that someone can pull up their bootstraps, make good choices, and stay safe and successful, it’s Scorcher. But by the end of the novel, the bloody triple-murder has rocked Scorcher’s earlier belief system to the core.

The Spains did everything right. The high school sweethearts walked down the aisle, got jobs, and responsibly invested in real estate, moving to a seaside town to raise their nuclear family’s requisite two kids. And then, based on circumstances entirely beyond the couple’s control, everything falls apart. Did the Spain family invite crime in? To what extent does any victim fulfill Kennedy’s rigid philosophy?

Tana French, The New York Daily News

Tana French, The New York Daily News

Self and Society

While Broken Harbour brings these issues to the fore, the shared culpability between an individual and their social circumstances structure all of French’s novels. In In the Woods, a horrific childhood trauma colors everything in detective Rob Ryan’s life, including his understanding of the murder case he’s investigating. Faithful Place begins with two teenagers who dream of escaping domestic violence and abject poverty. Their drive for freedom falls apart when it provokes another character to commit murder out of jealousy and resentment. After all, if they go free, he gets left behind in the slum.

In The Likeness (like Broken Harbour, another novel about land and property), a group of misfits try to opt out of normative society, with awful consequences. It begs the question, if regular society had more space for these wounded twenty-somethings, would their lives have turned out differently? The Trespasser explores cops trying to pin a brutal crime on an innocent man—all so they can protect one of their own. Apparently, being a detective means that you get one murder for free. And in The Witch Elm, French dissects the way that privilege structures all our lives with a devastating fable. After the main character’s fall from grace, he comes to know how the other half lives—and it is not pretty.

Tana French, Viking Penguin, Amazon

Tana French, Viking Penguin, Amazon

Detective Novels and Social Criticism

French’s nuanced exploration of violence separates her from the kind of exploitative literature that takes pleasure in the pain of a character—or in the case of true crime, a real person. Bottom-of-the-barrel true crime, in my opinion, limits itself to the murderer and their twisted perversions. The victim is around only to die, so that the writer can recount their grisly death with horrific detail.

French moves beyond the formula of "individual murderer + anonymous victim = thriller" by integrating broader social trends and a systemic angle. Her work implicitly rebuffs the usual idea of crime as isolated, aberrant, and fundamentally abnormal. While French never suggests that crime should become normalized, her novels point out that when viewed overall, crime has distinct patterns—and it should be considered in more complexity than “the murderer was a monster.”

Instead of laying blame firmly at the perpetrator’s feet, French encourages readers to think about the social circumstances that drove someone to criminality and to consider which factors enable some culprits to walk free while other people, not always guilty, rot in jail cells.