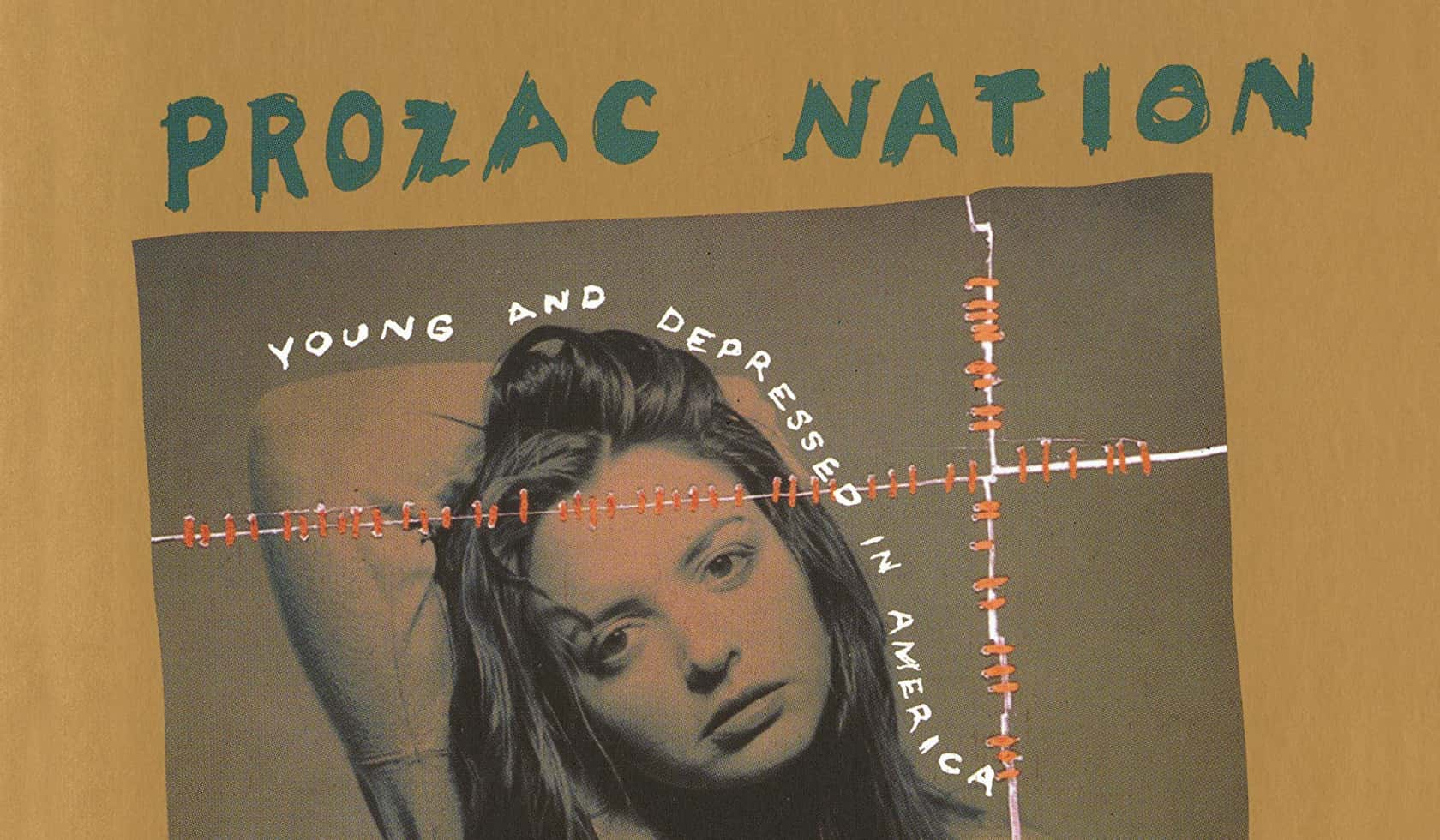

On January 7, 2020, Elizabeth Wurtzel, Generation X’s queen of confessional writing and the author of 1994's Prozac Nation, passed away. For those who haven't read Wurtzel's well-known memoir, the book may seem like just another example of the frenzied-yet-intimate writing found in most personal essays. But that would over-simplify Wurtzel's work: after all, she basically invented the overshare. After Prozac Nation, scores of people adopted Wurtzel's highly confessional writing—but even more maligned it and its creator.

In the collective imagination, Wurtzel was the “manic pixie dream girl” of the literary world. The fantasy of the beautiful, crazy writer clung to her and she faced skepticism and censure at every corner. Wurtzel wasn’t the first and certainly won’t be the last writer to suffer this fate. And yet, she forged through it all, providing a template for how to live and write unapologetically.

Elizabeth Wurtzel Editorial

Young and Depressed in America

On any alignment chart, Elizabeth Wurtzel would’ve stayed firmly in the chaotic side. She was born in New York City in 1967, growing up in the pre-Giuliani era of crumbling infrastructure and Times Square peep shows. By the time she was 12, she’d already had her first bout with depression and self-harm, complete with an overdose.

The ensuing teenage and college years were just as chaotic as Wurtzel's upbringing. After tempestuous relationships, substance use, and long depressive episodes, doctors eventually diagnosed Wurtzel with atypical depression. She became one of the first patients in the US to treat her depression with fluoxetine. Soon, she would chronicle these experiences in her 1994 book Prozac Nation.

Sign up to our newsletter.

History’s most fascinating stories and darkest secrets, delivered to your inbox daily. Making distraction rewarding since 2017.

Beautiful Insane Women Writers

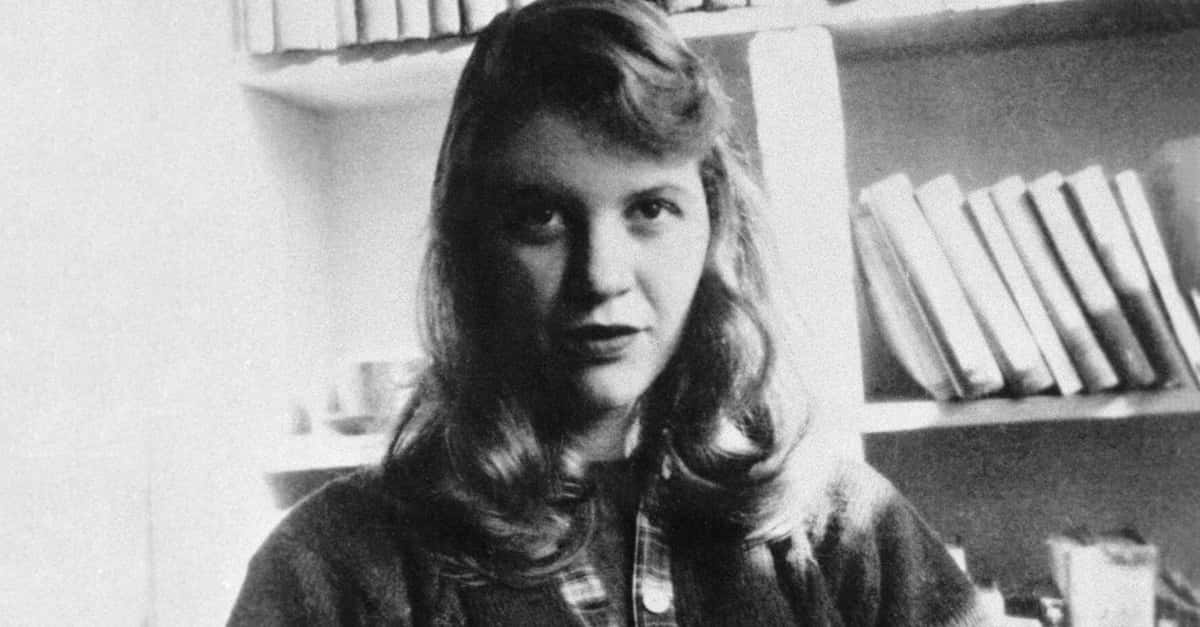

Despite her rambunctious personality and frenzied writing style, Wurtzel couldn’t escape comparisons with Sylvia Plath, another beautiful, crazy author figure. Fair enough, both had a record of rocky romantic relationships and overdose attempts, and in the best comparisons, critics used Plath to contextualize Wurtzel's work. But at the same time, naysayers weaponized these similarities against Wurtzel. Her harshest critics characterized her as flighty, self-obsessed, and tiresome. She was a pale imitation of dearly departed Saint Plath.

A year before Prozac Nation came out, Susanna Kaysen published Girl, Interrupted, a memoir about her time in a mental hospital. With her detached style, Kaysen eluded the critiques hurled at Wurtzel. A year later, Mary Karr’s memoir about her turbulent childhood, The Liar’s Club, would come out. Again, the establishment didn't pigeonhole her like Wurtzel. She is now a poet and professor, not just an overly emotional memoirist.

The Memoir Boom

Despite the fact that all three women were part of a so-called memoir boom, the differing reactions to each writer made it seem like the more personal the the memoir, the more it would be maligned. But shouldn’t intimacy be a memoir's strength?

The writing class 101 trope of “show, don’t tell,” didn’t seem to matter in Wurtzel’s case. While Kaysen narrated an exacting chronicle of what it was like to live in a mental hospital, Wurtzel’s breathless style made the reader feel like they were sharing in her manic episodes. It’s entirely likely that discomfort with this experience led to the some of the criticism directed at Prozac Nation.

[/media-credit] Wurtzel's final book CreatocracyFlickr Wurtzel's final book Creatocracy

[/media-credit] Wurtzel's final book CreatocracyFlickr Wurtzel's final book Creatocracy

"I Hate Myself and I Want to Die"

There could be a million different reasons why Prozac Nation rubbed some people the wrong way and made rabid fans out of others. After all, its title set up an expectation that the book didn't originally mean to fulfill. "Young and Depressed in America" made it seem like the memoir would treat a generational experience, but Wurtzel originally wanted another name for the book. She preferred “I Hate Myself and I Want to Die”—a title much better suited to its intensely personal contents.

She wanted her photo on the cover of the book, defying the faux-modesty that authors were supposed to embody, their headshots hidden on the back flap of dust jackets. Predictably, Wurtzel's naysayers criticized her audacity to claim her work so openly.

It goes without saying that much of the criticism hurled at Wurtzel smacked of misogyny, ageism, and professional jealousy. The New York Times, for example, published two reviews, with Michiko Kakutani praising Wurtzel and Ken Tucker lambasting her. In The Harvard Crimson, Erica L. Werner asked, "How did this chick get a book contract in the first place?” Werner forget to mention that Wurtzel had gone to Harvard and written for The Crimson herself. Wurtzel also won a Rolling Stone College Journalism Award while she was there.

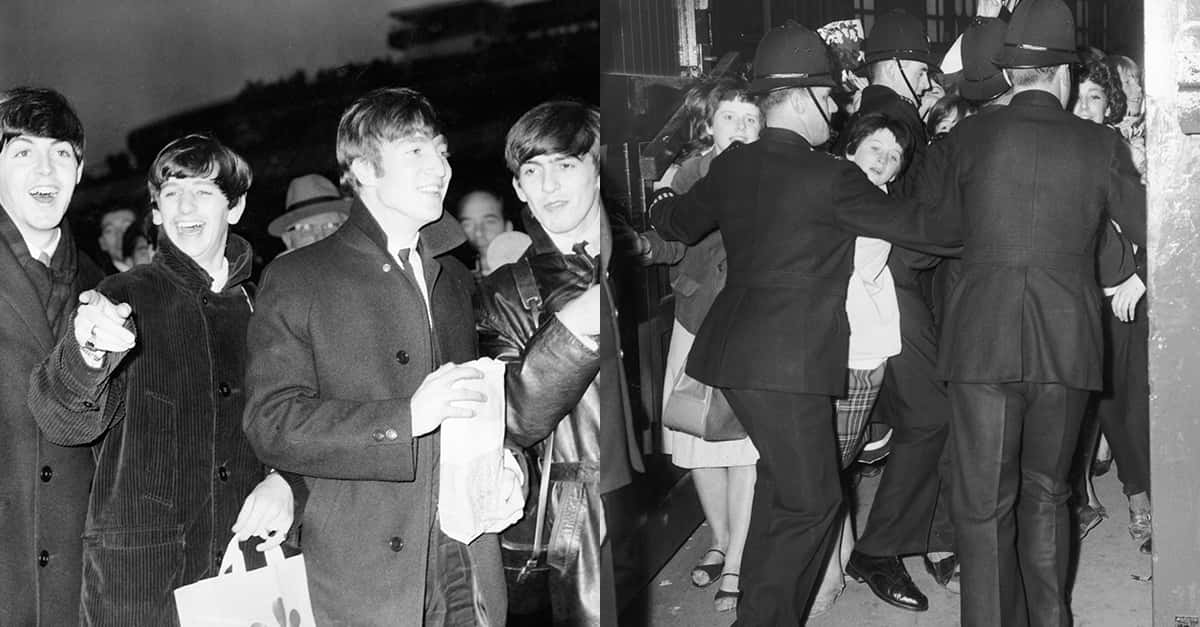

Then, there was her audience—a book about being “young and depressed in America” (actually Prozac Nation’s subtitle) inevitably found similar readers. There’s a rich history in literary criticism—or cultural criticism in general—of maligning things that young people, particularly young women, enjoy.

[/media-credit] Teenage girls were ridiculed for obsessing over the Beatles, now one of the most revered bands of all time. Getty Teenage girls were ridiculed for obsessing over the Beatles, now one of the most revered bands of all time.

[/media-credit] Teenage girls were ridiculed for obsessing over the Beatles, now one of the most revered bands of all time. Getty Teenage girls were ridiculed for obsessing over the Beatles, now one of the most revered bands of all time.

Defiant Women

Whatever the reasons for the vitriol faced by Wurtzel, it followed her for long after the publication of Prozac Nation. In 1998, she released her next effort. Bitch: In Praise of Difficult Women was a controversial, densely-packed treatise about unmanageable women and their misunderstood lives. In it, Wurtzel argued that living in a way in that society deems troublesome is the only appropriate response to an absurd world. Her thesis remains as incisive today as it was in 1998.

Wurtzel's next book More, Now, Again, grappled with addiction. Once again, the writer's return to a confessional subject garnered refrains of “Grow up/Shut up” from critics. They called her annoying and selfish and urged Wurtzel to be quiet, be smaller, feel less, and express less. Years later, we're beginning to recognize these reactions as inherently misogynistic (even if they still proliferate).

In a review of More, Now, Again for Salon, Peter Kurth wrote that, “The one thing about Elizabeth Wurtzel is that none of her troubles ever kill her.” She was the literary world’s cockroach. No matter how much life threw at her, from depression to fame to vitriolic criticism to addiction to aging, she kept going—and not only going, but forging ahead without shame or regret. Many critics waited for Elizabeth Wurtzel to grow up, in the sense that they wanted her to disavow her work or to show some sense of embarrassment for all the blood and guts she’d poured forth onto the page.

A One-Night Stand of a Life

One of Wurtzel’s last “blockbuster” pieces of work was an essay in New York Magazine titled “Elizabeth Wurtzel Confronts Her One-Night Stand of a Life.” The title alone likely left many expecting that this was the moment of reckoning. Finally, Wurtzel would lament the years she wasted doing what she wanted and writing what she wanted.

In the essay, Wurtzel confronts her own refusal to grow up and where it’s gotten her. She mulls over the things she’s missed in her life, but also the things she doesn’t regret. “I only write what I feel like and it has been lucrative since I got out of college in 1989.” How many writers can say the same? Replace “write” with “do,” and how many other people can say the same?

This is not to staunchly defend every letter of Wurtzel's work or her opinions, many of which were less than forward-thinking. Wurtzel lived her life entirely unapologetically and it made people angry. We should ask why that is, instead of trying to find resolution or the so-called ‘growth’ that she never agreed to provide us.

Coda

In hindsight, the New York Magazine essay, in its scope and depth, reads like a self-penned obituary. Wurtzel lays bare the faults and flaws that, for so many critics, made Wurtzel worthelss, but she does not apologize for them. She owns every ounce what she’s done in her life, the good and the bad—because she’s doing it by putting it down on the page, the thing she knows that she’s best at.

As Wurtzel puts it, “This story has the best possible ending, because I am telling it.” She may have written that line in 2013, but she was writing until the end—about her husband, her mother, and her cancer. In that sense, Elizabeth Wurtzel got her best possible ending.