Though he’s largely unknown in the Western world, Ibn Battuta was the greatest traveler in history. Over three decades in the 14th century, he covered more than 75,000 miles. He visited over 40 modern-day countries. He braved bandits and disease. He traveled on foot and by ship, in caravans and alone. He nearly died countless times. And when he finally decided to rest, after adventuring from Beijing to Timbuktu, he wrote a book detailing his remarkable years on the road. He called it A Gift to Those Who Contemplate the Wonders of Cities and the Marvels of Traveling. It’s usually just called the Rihla today. Marco Polo, eat your heart out.

Early Days

Not a whole lot is known about Battuta before he began his travels. His full name was ʾAbū ʿAbd al-Lāh Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd al-Lāh l-Lawātī ṭ-Ṭanǧī ibn Baṭūṭah. He was born in Tangier, in Morocco, in 1304. He was from a fairly well-off family of Muslim legal scholars. At age 21, he decided to embark on the hajj, the holy pilgrimage to Mecca that all able-bodied Muslims are expected to undertake. He left Tangier in 1325 with his sights set on the holy city. Little did he know, he wouldn’t return to his home for 24 years.

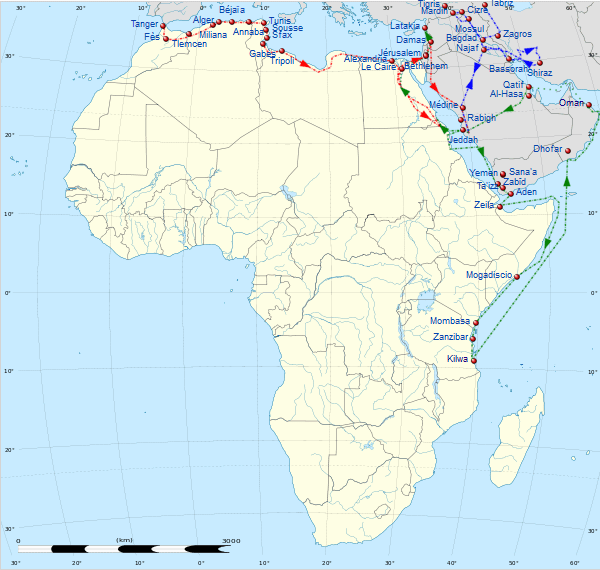

Starting off alone on a donkey, Battuta would connect with a caravan of other pilgrims working its way across North Africa towards the Holy Land. His first major stop was the city of Alexandria in Egypt, at the time a thriving hub on the Nile Delta. From there, he traveled down south to Cairo—though his destination was Mecca, even from the start, Battuta yearned to see as much of the world as possible. He rarely took the most direct route anywhere.

Wikimedia Commons Handmade oil painting reproduction of Ibn Battuta in Egypt, a painting by Hippolyte Leon Benett

Wikimedia Commons Handmade oil painting reproduction of Ibn Battuta in Egypt, a painting by Hippolyte Leon Benett

After a failed trip to the Red Sea, Battuta spoke with a holy man who said he would only make it to Mecca by traveling through Syria—so that’s exactly what he did. By taking this route, which included cities such as Hebron, Jerusalem, Bethlehem, and Damascus, Battuta got to enjoy relative safety from the bandits that had plagued his travels to this point. The ruling Mamluk Sultanate appreciated the importance of these holy places, and so they kept the road secure.

Holy Places

Though he wouldn’t record any of his travels until decades later, Battuta had much to say about these early days on the road. He called Alexandria a beautiful, well-built city. He described in detail the various Christian holy sites he visited in Jerusalem and Bethlehem. And above all else, he remembered Damascus, which he said, “surpasses all other cities in beauty.”

Battuta fell in love with Damascus and stayed there for the month of Ramadan, but he eventually continued his pilgrimage. He made the 1,300 km journey south to Medina, visiting the Mosque of the prophet Muhammad, then finally made it to Mecca, completing his first hajj (he would undertake several more before he gave up life on the road).

His sacred duty done, Battuta could have returned home. For many people, this trip of many thousands of miles would have been enough for a lifetime—but Battuta was just getting started. He claimed that he had a dream where he was picked up by a bird who flew him towards the east and left him there. Evidently, he told this to a holy man who said that it was his destiny to roam the Earth. As if the greatest traveler in history needed any more encouragement.

Dar al-Islam

It’s fitting that Battuta began his lifetime of adventuring by undertaking the hajj, because Islam would be what would allow him to travel as widely as he did. Many in the West may not realize it, but in the Middle Ages, the Islamic World, known as Dar al-Islam, was far larger than Christendom. It stretched from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific.

Since Battuta was trained as an Islamic judge and legal scholar, almost everywhere he went, the Muslim rulers he encountered treated him as an honored guest. If it weren’t for his religion, he never could have traveled as far as he did.

Wikimedia Commons Ibn Battuta in 1334 visited the shrine of Baba Farid in Pakpattan.

Wikimedia Commons Ibn Battuta in 1334 visited the shrine of Baba Farid in Pakpattan.

Just Getting Started

After his first hajj (he would end up taking several more), Battuta first traveled to Persia, in the ancient lands of Mesopotamia, eventually visiting Baghdad and Mosul. This leg of the journey nearly killed him, as he became terribly sick with diarrhea, but he managed to make it back to Mecca alive to complete his second hajj.

Still not satisfied, Battuta then headed south through the Red Sea and Yemen to the Horn of Africa. He visited the city of Mogadishu in Somalia and marveled at its great size and rich merchants. He continued down the Swahili coast, visiting the island town of Mombasa in modern-day Kenya, though it was at the time a relatively small settlement.

He eventually made it as far south as Tanzania, where he visited the city of Kilwa, which he considered “one of the finest and most beautifully built towns” that he encountered on his travels. But then Mecca called to him once again and he turned back north, returning to complete his third hajj.

Of course, he was not finished yet. His next voyage was to be his most ambitious yet—to visit the Muslim Sultan of Dehli, in the far-off land of India in the East. This would be the trip that would lead him to the very edge of the known world, but in typical fashion, he decided against the most direct route.

Heading East

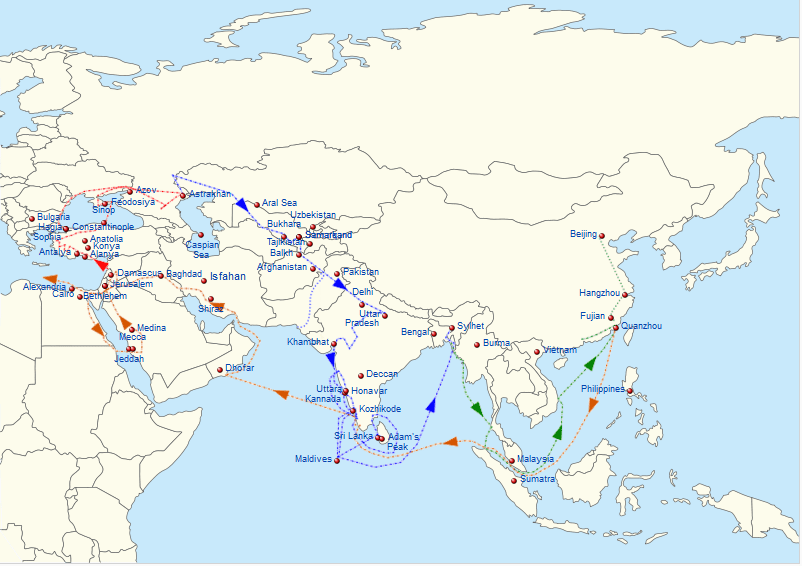

Instead of setting sail, Battuta decided to travel overland, following the Silk Road. And even in that, he needed to take a few detours. He traveled north to the Crimean Peninsula and the Caucasus Mountains, where he met with Uzbeg Khan of the Golden Horde. From there, he considered heading further north into “the land of darkness”—modern-day Siberia—but he decided against it.

Another opportunity arose when the Khan’s wife, the daughter of the Byzantine Emperor, wished to travel home to give birth to her child. The Khan granted permission for her to go, and Battuta somehow managed to finagle his way into the expedition to one of the world’s great non-Muslim cities: Constantinople.

Though it was one of the few places beyond the reach of Dar al-Islam that he visited, Battuta was still impressed by Constantinople. He recorded his visit to the legendary Hagia Sophia—but while he remarked upon his beauty, he decided that it would be better to not enter the Christian church.

After Constantinople, Battuta finally began traveling to India in earnest, following the same route that Alexander the Great had taken centuries before: through Afghanistan and across the Hindu Kush mountains. After a long and arduous journey, Battuta finally arrived in Delhi, utterly exhausted.

Wikimedia Commons Ibn Battuta itinerary of 1325-1332

Wikimedia Commons Ibn Battuta itinerary of 1325-1332

The Best is Yet to Come

He had already journeyed tens of thousands of miles and had undoubtedly seen more of the world than any else alive, but if there’s one thing any traveler can agree on, it’s that the world will never cease to surprise you.

By 1333, Ibn Battuta was already the greatest traveler in the world. He'd been on the road for eight years. From his home in Morocco, he’d traveled tens of thousands of miles. He’d visited the Holy Land, Africa, and Constantinople. He’d followed Alexander the Great’s footsteps across the Hindu Kush mountains and found himself in India, in the company of Sultan Muhammad bin Tughluq, one of the richest men in the entire world. This would seem a comfortable place to end a life of traveling—but Battuta was just getting started.

India to China

When Battuta arrived in Dehli, he was treated as an honored guest. After all, he was a distinguished Islamic judge and legal scholar. He had visited Mecca several times. Such people did not pass through the far-east city of Dehli very often.

Battuta lived in Dehli for several years, but it was not a particularly enjoyable time. The Sultan was infamously erratic. He had a fiery temper and was subject to wild mood swings. He could be unbelievably bloodthirsty—one of his preferred methods of execution was to throw his enemies to the mercy of enraged elephants with wicked swords affixed to their tusks.

Working for such a man was never comforting, and Battuta spent his time in Dehli searching for a way out—to get back on the road that he loved so much. The Sultan, however, didn’t want his esteemed Islamic scholar to leave. When Battuta suggested the idea of returning to Mecca on another pilgrimage, the Sultan vetoed the plan.

Battuta seemed trapped, but the chance to escape finally arose in 1341. That year, an embassy from the distant and enigmatic China appeared in the city. The Sultan decided that he should send his own embassy back, and selected Battuta to lead the caravan.

He was heading back out on the road, and this latest adventure would take him beyond the Islamic world to a land that few Muslims had ever seen.

Wikimedia Commons Ibn Battuta Itinerary 1332-1346 (Black Sea Area, Central Asia, India, South East Asia and China).png

Wikimedia Commons Ibn Battuta Itinerary 1332-1346 (Black Sea Area, Central Asia, India, South East Asia and China).png

Sabbatical in Paradise

Few of Battuta’s travels were ever easy, but the trip to China was particularly rough. First, the ship carrying him, his caravan, and all of his luggage, sunk. He barely made it back to India alive, and he found himself stranded, penniless, and alone. He was also loath to return to Dehli—the Mad Sultan likely wouldn’t take the news of his failure well.

So, Battuta did what he always seemed to do: he took a detour. Still determined to make his way to China, he sailed south for the tropical islands of the Maldives. There, as usual, he worked as an Islamic judge, staying in the tropical paradise for almost a year. The Maldives had just recently converted to Islam, and his knowledge was in high demand.

The Final Leg

No one would blame Battuta if he finally hung up his hat in the Maldives, but the East still called to him. His conservative nature also conflicted with the free-spirited islanders—he never quite got used to the way that women wore no clothing above the waist.

After finally leaving the Maldives, Battuta passed through Sri Lanka, then voyaged to the Samudra Pasai Sultanate on the island of Sumatra. He was impressed with the island’s vibrant landscape and with the Sultan’s piety, even at the furthest extent of Dar al-Islam. But the next leg of his journey would finally take him beyond the eastern border of the Islamic world. He was finally going to China.

Stopping briefly on the Malay Peninsula, which he called “Mul Jawi,” Battuta finally made landfall in China—reaching the city of Quanzhou in 1345, four years after he’d left Dehli.

Sign up to our newsletter.

History’s most fascinating stories and darkest secrets, delivered to your inbox daily. Making distraction rewarding since 2017.

The Sleeping Dragon

When he arrived in China, Battuta found other Muslims waiting for him. He even met a man named Al-Bushri from his native Morocco, who had become a wealthy merchant. He was as far from Mecca, the epicenter of the Dar al-Islam, as he would ever be, yet he still found lodging and safe travel through his religion.

In China, Battuta wrote of enormous cities, beautiful landscapes, and gigantic ships. He even claimed to have traveled as far as the Grand Canal and Beijing (though some modern historians doubt he made it quite that far). He also provided the earliest non-Chinese mention of the Great Wall, though he never saw it himself.

As the long-lost ambassador of the Dehli Sultanate, he visited the court of the Emperor, a Mongolian named Togon-temür, of the Yuan Dynasty. He had finally made it. All that lay in front of him was the Pacific Ocean.

Wikimedia Commons Ibn Battuta itinerary of 1332-1346

Wikimedia Commons Ibn Battuta itinerary of 1332-1346

The Road Home

After getting to China and exploring the landscape, Battuta finally set his sights on his home—a place he hadn’t seen in over two decades. His return trip was relatively straightforward. By 1348, he was back in his favorite city in the world: Damascus. I doubt anyone would blame him for skipping a reunion with the Mad Sultan in Dehli.

From Damascus, he retraced the steps of his first hajj, all those years ago, and returned to Mecca once more. Then, finally, he decided to head home to Tangier—though he just had to stop in Sardinia on the way back. This was a man who’d never taken the fastest route anywhere. He wasn’t about to start now.

He finally made it back home late in 1349. He’d traveled further than anyone else in history, but it was finally time for this great adventurer to rest...

…or not. He was only in Tangier for a mere four days before setting back out again, this time heading to fight Christians in Gibraltar.

Can't Stop Won't Stop

By the time he made it to Gibraltar, the threat had passed, so he turned around and headed back home—though he was sure to stop in Valencia, Granada, and Marrakech on the way. He made it back to Tangier, and finally, the great traveler was finished.

Just kidding. He’d never traveled across the Sahara Desert—how could he stop before that? On what was one of the most grueling trips he’d ever undertake, the aged Battuta joined a caravan and made the treacherous voyage across the brutal sands of the Sahara. It took two months to make the 1,000-mile trek, jumping from oasis to oasis, but he eventually made it to the lands of the great Mali Empire. He sailed along what he thought was the southern extent of the Nile River (he was a bit off on that, it was actually the Niger), and he met the leader of Mali: Mansa Suleyman.

While in Western Africa, Battuta visited the legendary city of Timbuktu—though when he passed through, it was a relatively small and unimportant city. He was about 200 years too early in that regard. He also encountered a hippopotamus, one of the most fearsome creatures he’d seen in all of his adventures.

After traveling further down the Niger in a dugout canoe, visiting the vibrant and wealthy city of Gao, he turned back home for the last time. He arrived back in Morocco, and after nearly three decades, put his days on the road behind him. He’d covered over 75,000 miles, but his great journey was at its end at last.

A Gift

When he finally made it home, he decided to share his experience with the world. He teamed up with a scholar to write A Gift to Those Who Contemplate the Wonders of Cities and the Marvels of Travelling, better known as the Rihla. From memory, he recounted his unbelievable journeys.

His book is a record of the 14th-century world unlike anything else in existence. Though he undoubtedly got some things wrong in his recollections—he didn’t keep a journal as he traveled—his account gives us a picture of the social, political, and geographical climate of the vast array of cities and cultures he visited. In the Western World, we tend to learn only about the history of Europeans. The Rihla gives a vivid picture of the remarkable civilizations that existed around the Indian Ocean in the 14th-century, outside the Christian World.

After the Rihla was completed, in 1355 Ibn Battuta seemed content with a life of obscurity. We know very little about the rest of his life. It’s thought that he spent his final years working as a judge in Morocco. He likely died around 1368, but no one knows for sure. And so the world quietly lost the greatest traveler it would ever know, but even centuries later, his unrelenting curiosity to see what the horizon had to offer can serve as inspiration for any other adventurers who want to follow in his footsteps.