When Samuel Johnson died in 1784, he left inheritances to prominent figures like the author Bennett Langdon and the painter Joshua Reynolds. Amid their well-regarded company, Johnson surprised society by bequeathing an unexpected person with a generous gift.

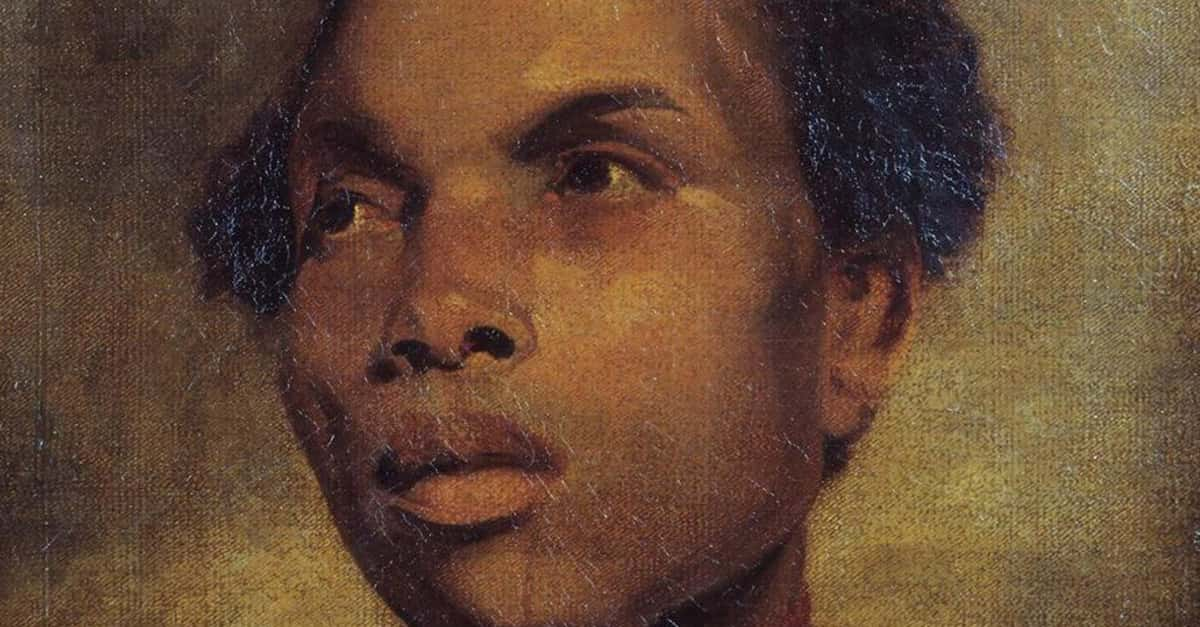

He gave his “man-servant” Francis Barber £70 (the modern equivalent of £8,000). While it wasn’t uncommon for masters to provide for their staff after death, Barber presented a unique case. Barber was a Black man.

Strange Recollections

Barber, whose original name was Quashey, entered a bleak situation from birth. His parents were slaves on the Bathurst family’s Jamaican sugar plantation—and if several chance encounters didn’t occur, Quashey would have repeated their terrible fate. Instead, he became a crucial part of London’s literary scene.

The life of Francis Barber, as he was soon re-christened, asks us to reconsider our idea of the white-washed 18th century often depicted in lush period dramas. People of color could—and did—live in Regency London, but their place in British history is hard to grasp.

After all, they lived in the so-called Age of Enlightenment, where scientific advances and humanist philosophy co-existed with the horrific slave trade. Accounting for people of color and their experiences in the 18th century makes us pause and wonder about the history we remember and the unsavory realities we repress.

Wikimedia Commons J.M.W. Turner, The Slave Ship, 1840

Wikimedia Commons J.M.W. Turner, The Slave Ship, 1840

Barber’s Roots

While young Barber’s memories are lost, others recorded their chilling observations of the "Triangular Trade" in the 18th-century. For example, diaries by the plantation owner Thomas Thistlewood record the sadistic punishments inflicted on his chattel in Jamaica. It’s very possible that Barber endured similar conditions.

Family Secrets

When Barber was seven years old (though historians debate his birth date), his entire life changed. The boy’s owner, Colonel Bathurst (who some historians suspect may have been Barber’s biological father—mixed-race children were not uncommon on plantations), plucked him out of Jamaica, brought him to England, and enrolled him in school.

After two years in Yorkshire, Bathurst established Barber in London. In April 1752, he left the boy on the doorstep of his son’s good friend, the esteemed writer Samuel Johnson.

Wikimedia Commons Samuel Johnson

Wikimedia Commons Samuel Johnson

Enter, Samuel Johnson

When young Barber first met the respected lexicographer, Johnson was 42 years old, but felt far older. After losing his wife a mere two weeks before Barber’s arrival, Johnson’s usual depressive spells had worsened. But even discounting Johnson’s grief and mental health issues, the writer still faced many struggles.

Johnson suffered from numerous ailments—everything from partial blindness to Tourette syndrome—with the press constantly mocking his physical disfigurement. For all his bluster, Johnson never felt like he belonged in London society. Seeing Barber as a fellow outsider, he took the young boy under his wing.

After a few years with Johnson, Barber received news that must have left him with mixed emotions: Colonel Bathurst was dead. The man who had both confined and liberated Barber was no more—and with his death, Barber gained official freedom (and a £12 inheritance to boot). For the first time in his life, Barber could do as he pleased.

Coming of Age

Barber decided to leave Johnson’s home, though the pair stayed in touch, and broaden his horizons by working at an apothecary. Soon after, he switched careers and volunteered for the Navy, sailing with the HMS Stag for two adventurous years before returning to Johnson. But that’s not exactly the whole story.

Like any overbearing parent, Johnson didn’t approve of Barber’s dangerous career choice. He was desperate to set Barber up with a better (and less life-threatening) job, with Johnson begging one of his harshest critics, the politician John Wilkes, to intervene and get Barber back home. In a letter, Johnson made a friend tell Wilkes about how Barber was “a sickly lad”—but it’s clear that Barber wasn't really the problem. It was Johnson, who found himself in “great distress” without his surrogate son.

School Days

Johnson’s interference couldn’t have thrilled Barber who, after all, chose to join the Navy, but at least Johnson put his money where his mouth was. When Barber returned in 1760, Johnson paid a considerable sum (£300) for five years of Barber’s education, hoping that enhanced schooling would help the young man net a stable career, perhaps as a missionary.

After Barber’s training, he put his newly-acquired skills to work for, of all people, Samuel Johnson. Barber acted as the literary titan’s personal assistant, handling Johnson’s paperwork and organizing his travel. While we can only speculate about Barber’s life outside of Johnson’s home, we do know that in 1773, Barber’s whole world changed for the better. He married a woman named Elizabeth Ball.

Weddings and Funerals

Sadly, the Barbers’ marital bliss was cut short. Neighbors mocked the interracial couple by calling them Othello and Desdemona. Even worse, their first child died before his second birthday. Thankfully, after this devastating loss, things began to improve.

The couple’s second baby (who they named Samuel) survived, with two more healthy children to follow. Throughout these highs and lows, Johnson was there, supporting the young couple who actually shared the lexicographer’s London home. But these happy times couldn’t continue forever.

The End of an Era

In 1784, Francis Barber was one of only two people present when Samuel Johnson passed away. To return to the scandalous will that began this article, Johnson left Barber a generous annual payment and a golden watch, along with the writer’s valuable books and papers. To the end, Johnson held his surrogate son in high esteem, literally trusting him with his life’s work.

After Johnson’s death, Barber moved to Lichfield (Johnson’s home town) and attempted to found a school, where he would serve as England’s first Black schoolmaster. After many years with Elizabeth and his children, Barber died in 1801. In a sweet coincidence, his eldest son Samuel fulfilled Johnson’s dream for Barber, becoming a preacher.

Shutterstock Lichfield Cathedral

Shutterstock Lichfield Cathedral

Who Was Francis Barber?

In some ways, Francis Barber lived an uneventful life. Like many men in the lower middle class, he tried his hand at a few career paths, sailed with the Navy, married a woman, and dealt with a meddling parental figure.

And yet, Barber’s race factors into everything. When Johnson left him a generous provision, his bequeathment scandalized society. After Barber married a white woman, neighbors called the couple cruel names. When John Hawkins published a biography of Johnson, he ran Barber’s name through the mud.

12 Years a Slave, Fox Searchlight Pictures

12 Years a Slave, Fox Searchlight Pictures

History's most fascinating stories and darkest secrets, delivered to your inbox daily.

The Trouble With History

These biases emerge in quieter ways as well. Johnson’s friend Mrs. Piozzi claimed that Barber became so overcome by how men responded to his beautiful wife that Johnson needed to calm him on a long walk. Could this be true, or is it another version of the townspeople’s Othello comparisons? This anecdote shows how hard it is to detangle Barber from the discrimination that surrounded him.

Like many people of color in 18th century England, our ideas of Barber are informed not by Barber himself, but the biased society in which he lived. This isn’t frustrating just because it makes research significantly more difficult, but also because it replicates the challenges faced by Barber in his life. After years of being over-determined by English society, it is hard to confront the idea that our research, no matter how well-intentioned, can never redress that damage or worse, may even repeat it.

But at the end of the day, not discussing Barber for fear of doing it wrong or incompletely doesn’t get us anywhere either. His story matters not just for what it can tell us about Samuel Johnson or London society, but because it tells us about Barber himself, a person more than worth our consideration.