Today, if a friend or family member shared that they’d been diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes, it would surely be a cause for concern, but not the end of the world. It may necessitate a combination of daily insulin injections and lifestyle changes, but it wouldn’t carry the same weight as a diagnosis of cancer or any seriously debilitating disease.

But what many people don’t know is that up until the early 20th century, a diagnosis of Type 1 diabetes was quite literally a death sentence.

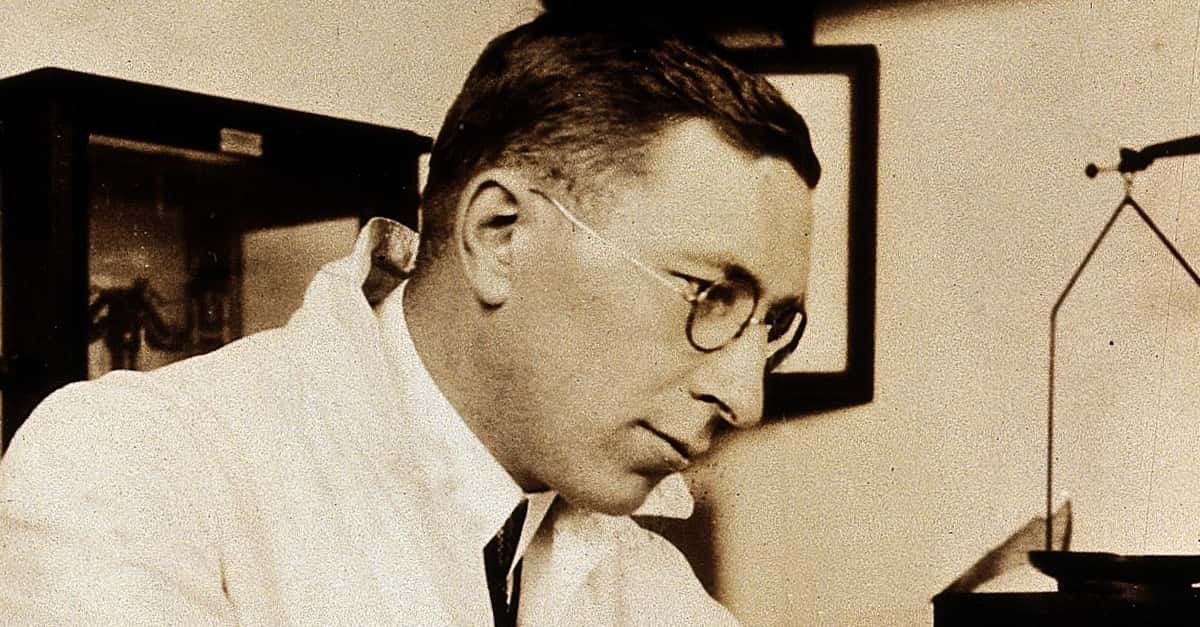

Wikimedia Commons Charles Best and Frederick Banting

Wikimedia Commons Charles Best and Frederick Banting

Before 1922, a diagnosis of Type 1 diabetes meant that the patient had, at most, 1-2 years to live—and in that time, they’d experience fatigue, pain, and discomfort before slipping into a diabetic coma. Then, in one of the most dramatic moments in the history of medicine, a team of doctors were able to isolate insulin, and suddenly scores of patients were saved from the brink of death. Rarely has a discovery in the field of medicine had such a dramatic and immediate effect.

Know Your Enemy

To understand why the isolation of insulin was such an important breakthrough, we first have to understand how Type 1 diabetes effects patients, and how it’s been understood historically. Early medical accounts from circa 1500 BC in ancient Egypt and India described an affliction involving “too great emptying of the urine” and “honey urine,” respectively. Both of these descriptions seem somewhat obtuse, but are actually quite accurate characterizations of the symptoms of Type 1 diabetes.

The condition typically strikes children, which is why it’s sometimes known as "juvenile diabetes." In Type I Diabetes, the pancreas fails to produce insulin, a hormone that helps to regulate sugar (in the form of glucose) in the blood. Untreated, this will lead to sugar building up in urine, hence symptoms of frequent urination (“too great emptying of urine”) and sugar being expelled in the urine (“honey urine”—physicians noticed that ants were attracted to the urine of patients who suffered from the condition).

In ancient Greece, the condition was given the name "diabetes" (which means "to pass through), and accounts that mention that word describe what life with it was like: the Greek physician Aretaeus said that “life [with diabetes] is short, disgusting, and painful.” Back then, doctors were powerless to help the patients they diagnosed with diabetes, and had to watch families mourn as their children slipped into comas and away from this world.

The condition basically remained a death sentence for those who suffered from it for thousands of years—until a pair of Canadian medical scientists began the work that would change everything.

Diabetes: The Dawn of a New Age

Canadian medical scientists Sir Frederick Grant Banting and Charles Herbert Best revolutionized diabetes medicine, but they didn't do it alone. The stepping stones for their work were laid out by other physicians and researchers who came before them—including those who discovered the role of the pancreas in diabetes, those who identified the cells that produced what came to be known as insulin, and those who discovered insulin itself.

Working from the jumping off point provided by the valuable work of their predecessors, Banting, Best and their team were able to come to a greater understanding of the role the endocrine gland plays in pancreatic function. Most importantly, they were also able to isolate the hormone insulin, making it a viable treatment for their patients.

A 1920 scientific article observed that in a certain procedure, pancreatic cells secreting the substance trypsin—which breaks down insulin and was thus inimical to Banting's efforts—could be destroyed without damaging insulin-producing cells. Using this research, Banting and Best were able to isolate insulin, and they then enlisted a biochemist by the name of James Collip to help them purify the formula.

Finally, in January 1922, they were ready to try the insulin cure on a human subject for the very first time—but both tragedy and disappointment struck that day.

At Death's Door

In our modern era of astounding medical advancements and extensive and regulated drug trials, those of us outside of the world of medicine are rarely given an opportunity to think about how something transforms from an idea into an approved treatment, but the history of medicine is riddled with stories of trial and error—some causing great harm, and some even fatal. The first attempt at using insulin is one of these stories.

Wikimedia Commons Frederick Banting

Wikimedia Commons Frederick Banting

On January 12, 1922, a 14-year-old by the name of Leonard Thompson was injected with one of Collip’s batches of insulin, but the formula was not pure, and he suffered a severe allergic reaction. Though his life was in great danger, Thompson held on—and it’s a good thing he did.

The experiment could very nearly have ended there, but the team of Banting, Best, and Collip knew that no one else had ever come that close to a treatment for Type 1 diabetes before, and they had to soldier on. Collip worked tirelessly to further purify the insulin, and within 12 days, they were ready to try again—after all, a ward of young patients and their families were at death’s door. They returned to Toronto General Hospital and performed, before everyone in the ward, what must have seemed like a miracle.

Wikimedia Commons Toronto General Hospital

Wikimedia Commons Toronto General Hospital

Soon after their success with Thompson, the three-man team went from bed to bed, injecting each Type 1 diabetes patient with insulin. Suddenly, children were waking up from the diabetic comas they’d been in, much to the delight of their families—not to mention the nurses and doctors, who’d been caring for them and hoping beyond hope that a treatment would come.

Hitting the Big Time

In the midst of their research, Banting and Best were approached by drug manufacturer Eli Lilly and Company, who had the resources to refine and mass-produce insulin. Within months, it was made available to the general public, and in a short span of time, Type 1 diabetes was no longer a death sentence. Recognition followed: In 1923, Banting was awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine (he shared his money with his partner Best), and Banting and Best were soon decorated with countless other honors.

The term “medical miracle” is often seen as hyperbole, if not a sign of an outright scam or hoax. But, despite the problems they ran into along the way, Banting and Best’s team persevered, delivering a real and true medical miracle to generations of patients and their families. While the production of insulin has shifted in recent years from pork and bovine sources to bacteria, millions of patients who might otherwise have fallen into a diabetic coma are still able to use insulin daily to control their conditions—and to live.