Cholera, left untreated, can kill you in hours. It's highly contagious, fast-acting, and incredibly resilient. Anywhere a human population has reached significant size, without also reaching certain standards of cleanliness, cholera is in danger of spreading...

And yet today, for the majority of the developed world, contracting cholera is as much of a threat as spontaneous combustion.

What changed?

Before the 1800s, it was the scourge of every city. Its causes were a mystery to the most respected scientists of the day—a reliable cure was essentially science fiction. Today, it's largely a disease of only the poorest and most disadvantaged places on Earth.

This is the story of how one man radically shifted our understanding of how diseases spread, and how we can protect ourselves in the future. It’s also a roadmap for solving massive problems with out-of-the-box thinking.

It’s the story of a man named John Snow.

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

London in the Time of Cholera

If a time-traveling peasant from the 1800s came whirling through the ages to a modern city, circa 2018, the thing that would shock them most might easily be the sheer lack of poop in the streets.

Picture for a moment the astounding amount of waste produced in any human settlement, every single day. The cleaning and bathing. The disposal of food waste. People pooping…

Imagine the sewage that is produced in a single New York minute.

Now subtract from that mental image any semblance of a modern sewer system. No running water. No washing your hands. And no toilets. The equivalent of “flushing the toilet” for your 19th-century Londoner might mean hucking a bucket of raw waste into a massive open-air pit known as a “cesspool”... conveniently located just steps from your house. A really health-conscious person might cover it with dirt afterward. As for getting water, the solution was similarly primitive: citizens would often collect it by the barrel from town wells or communal pumps.

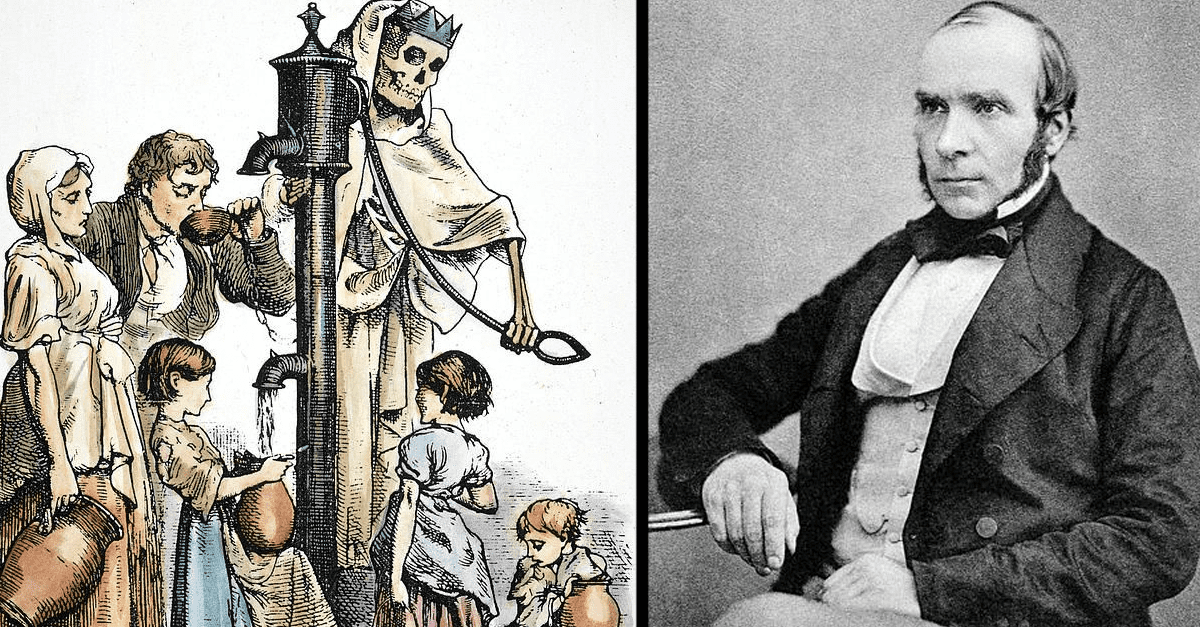

So maybe it shouldn't be surprising that in 1854, London was suffering through the latest in a series of massive, deadly cholera epidemics. And yet at the time, the causes of such pandemics were utterly unknown. The disease was sweeping through the city with alarming speed... and the greatest scientific and medical minds of the time had no clue how to stop it.

John Snow, Our Hero

John Snow, like all great heroes, was not the man you’d expect to save the day.

Wikimedia Commons Game of Thrones character he was not

Wikimedia Commons Game of Thrones character he was not

When London was hit by one of the first of its great Cholera epidemics, Snow was in no position of power at all. He was an unmarried, non-drinking, vegetarian scientist with a gift for math. As noted by his profile on UCLA's website, "his social life consisted mainly of discussing ideas at the regular meetings of the Royal Medical and Chirurgical Society."

Cool. He was also (you might have noticed) not particularly blessed in the looks department.

But Snow had a secret weapon: he was a skeptic. His primary point of skepticism? The miasma theory of disease.

The miasma theory held that the world's deadliest pathogens were caused simply by "bad air"— the result of pollution and rotting food. This theory was state of the art in the medical establishment for literally thousands of years.

Because odor was considered the only reliable sign of that bad air, the logical solution to an outbreak of disease (according to someone operating with this belief) was to fix the smell. Dumping a barrel of excrement in the town square was only an issue if the smell got too bad afterward. Never mind germs or bacteria…those ideas didn’t even exist yet.

Getty Images Life in London probably felt a lot like this

Getty Images Life in London probably felt a lot like this

John Snow, though, had another theory: what if cholera wasn't spreading through the air at all?

During an earlier outbreak, Snow worked as a graduate student in the vanishingly-small village of Killingworth. While there, he noticed that miners were blighted with cholera despite working deep underground. There were no sewers or cesspools or swamps. How could they be suffering from bad air? Snow figured it was more likely that cholera had spread by invisible particles on the hands of the miners. And, he speculated, those same particles might also be transmitted through a city's water supply.

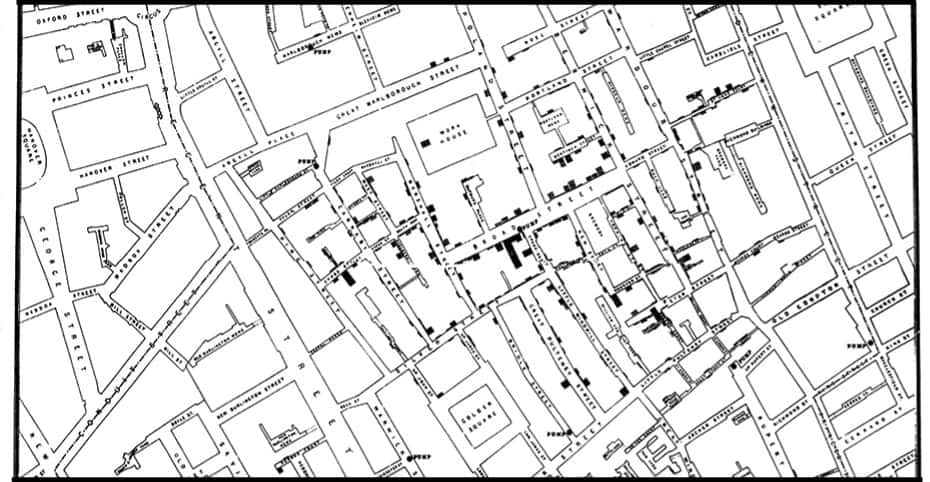

And so, guided only by his gut, Snow began mapping cases of cholera in London.

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

Well, Well, Wells…

Soon after beginning his research, Snow began to suspect that the main culprit for the 1854 outbreak was the Broad Street Pump. As he noted:

"Within 250 yards of the spot where Cambridge Street joins Broad Street there were upwards of 500 fatal attacks of cholera in 10 days… As soon as I became acquainted with the situation and extent of this eruption of cholera, I suspected some contamination of the water of the much-frequented street-pump in Broad Street."

Remember: getting water in 19th-century London didn't mean turning the tap on. Private residents fetched their water from the local well. Businesses got theirs from teams of water distributors, not unlike milkmen. As you can imagine, that meant that if one well were to be infected with, say, cholera... every person in the nearby area was likely going to be drinking it soon enough.

From his maps, it seemed clear that cholera was spreading from the Broad Street Pump...but was it enough? To further prove his theory, Snow went door-to-door in the area, interviewing the residents. He soon found that those who preferred water from Broad Street almost invariably came down with illness. All in all, it seemed that every clue pointed to the one pump.

Eventually, Snow felt he'd gathered enough evidence to present to local authorities. He made an impassioned plea to officials that simply removing the handle on the Broad Street Pump (thereby rendering it useless) would end the cholera outbreak. They agreed to try Snow's bold measure...

And it worked. Within days, the outbreak slowed and, eventually, stopped. (And sure, the outbreak may have already been in decline, but let's give the guy some credit here.)

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

Father of Epidemiology

An epidemiologist is a scientist who studies the spread of disease. John Snow might as well be their patron saint.

But shockingly, soon after the immediate threat had seemingly passed in London, officials replaced the handle on the Broad Street Pump without doing a thing to change the cleanliness of the water. Though they'd listened when things were dire, they were still unwilling to totally accept Snow's theory that cholera was spread by particles of fecal matter in the water. It was deemed "too unpleasant" for the general public to embrace. It would be years before Snow's theory was fully accepted.

But Snow is remembered for more than just this. He revolutionized our understanding of how disease spreads by popularizing the idea that tiny, invisible specks (germs) could transmit illness through water or physical contact. That's a massive achievement by itself. But he also popularized another, possibly more important aspect of modern science: the double-blind experiment.

The Double-Blind

In a double-blind experiment, neither the participants nor the researcher knows which group is being exposed to the substance being tested (in this case, dirty water) and which group is receiving a placebo (clean water). Snow's work during the outbreaks with multiple water companies that were drawing from different sources, one pure and the other impure, allowed essentially the same double-blind conditions. As Snow wrote:

Each [water] company supplies both rich and poor, both large houses and small; there is no difference in the condition or occupation of the persons receiving the water of the different companies... no experiment could have been devised which would more thoroughly test the effect of water supply on the progress of Cholera than this...No fewer than three hundred thousand people of both sexes, of every age and occupation, and of every rank and station, from gentlefolks down to the very poor, were [unintentionally] divided into two groups... one being supplied water containing the sewage of London, the other group having water quite free from such impurity."

- John Snow, On the Mode of Communication of Cholera

It was a perfect experiment. One company drew water straight from an impure source, and the people who drank it inevitably became sick. Meanwhile, those drinking relatively clean water from a clean source were unscathed. And best of all? Snow could only find out where a household got its water supply by testing it, ensuring a double blind.

Once again, Snow had proven himself correct.

Lessons for Today

Dogma is defined as: "a principle or set of principles laid down by an authority as incontrovertibly true."

That's what Snow was fighting. A deeply ingrained belief (in his case, the miasma theory) that wasn't supported by any real evidence.

Getty Images

Getty Images

It's hard work. As Snow's story shows, just because you present a logical, well-built case to people, it doesn't mean you'll be able to change any minds right away.

Indeed, Snow's discovery seems pretty obvious today. How could we ever have not known about germs? Even still, it took years of his life, as well as the work of later scientists, to prove he was right. In that way, he deserves a place in the long line of geniuses ahead of their time: Galileo, Darwin, etc.

But Snow's story also shows the value in that type of thinking. Questioning the most basic, seemingly obvious principles of their time is something almost all great innovators do.

It's also risky, unpopular, and downright difficult. It takes an amazing amount of courage to doubt when everyone around you believes, as well as an equally impressive degree of self-awareness. After all, how many of us really ask how we know the things we know?

It's a skill we could all stand to improve.