Joseph Frank “Buster” Keaton was born in 1895 in Piqua, Kansas, but that's not really where he's from. That’s just the town where his parents happened to be when his mother went into labor. Joe and Myra Keaton spent their lives was traveling the country performing in theatres and dance halls, and they didn’t stop when their son, whom they named after his father, was born.

No, Buster Keaton wasn't from Piqua, Kansas. He was a performer from the very start. His only home was up on stage. Young Joe was just three years old when his parents brought him into their act. Performing was all he knew—and he happened to be born at the perfect time to take advantage of the new medium that would completely change the face of show-business: Film.

His Vaudevillian childhood perfectly prepared him for a career in front of the camera. Before the days of stunt doubles and CGI, his utter fearlessness made for some of the most remarkable films of the silent era—and he managed to do all of his death-defying stunts with his iconic deadpan expression. It's no wonder that Roger Ebert claimed The Great Stone Face was “the greatest actor-director in the history of the movies.”

A Buster is Born

Keaton's parents were major players in the Vaudeville circuit, and they rubbed elbows with some of the most iconic performers of the time—including the world's most famous escape artist: Harry Houdini. So the story goes, it was actually Houdini who gave "Buster" his famous nickname.

Allegedly, Houdini once watched an 18-month-old Joseph Frank Keaton fall down an entire flight of stairs, then simply get up at the bottom, completely unscathed. The magician then looked to the Keaton parents and said, “That’s some buster your kid took!” They must have liked the sound of it, because the name stuck.

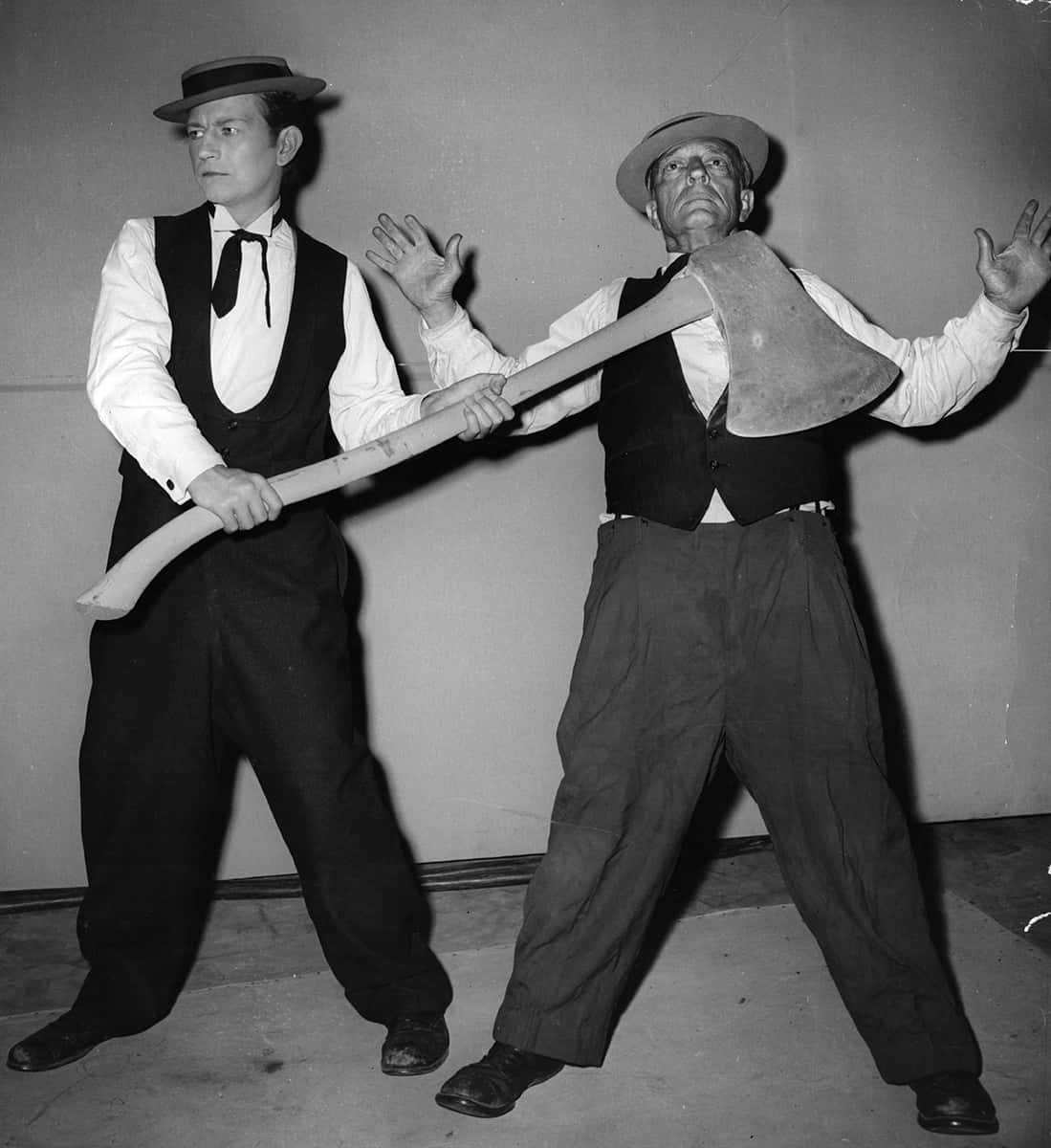

Getty Images Buster Keaton and Donald O'Connor

Getty Images Buster Keaton and Donald O'Connor

Apparently, Houdini wasn't the only one who noticed the toddler’s predilection for pratfalls, because the Keatons incorporated their son into their act not long after, renaming themselves “The Three Keatons”—and let's just say, their schtick wasn't exactly safe for a small child.

The Little Boy Who Can’t Be Damaged

The Three Keatons’ show would never fly today—it was barely even considered legal at the turn of the century. For the most part, it involved Keaton’s mother playing the saxophone while he and his father took center stage.

Young Buster would provoke his father in one way or another, and an enraged Papa Joe would respond by heaving his son against the scenery, or sometimes out into the audience. They even sewed a suitcase handle onto Buster’s clothes for more impressive throws.

While audiences loved this Vaudevillian equivalent of Homer Simpson strangling his son Bart, the authorities were less-than-pleased. The New York Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children had a particular bone to pick with this so-called “act.”

But while cries of child abuse unsurprisingly followed the Three Keatons almost anywhere they went, Buster himself was always quick to show them that he never had any bruises or broken bones. Because while most children would probably be utterly terrified, the young Buster absolutely loved the show he did with his parents.

Buster Keaton: Pratfall Prince

Keaton learned (by necessity) how to safely fall almost as soon as he could walk. He called landing right “second nature,” and it was this extraordinary acrobatic ability that would make his future films so remarkable. While the audience may have gasped when they saw Joe Keaton whip his son across the stage, the boy himself was having the time of his life, completely confident of his safety.

Getty Images Buster Keaton, Captain Lew Cody, and Jimmy Durante

Getty Images Buster Keaton, Captain Lew Cody, and Jimmy Durante

In fact, young Buster loved being thrown about so much that he often found himself laughing as he soared through the air. But, even from a young age, he was a master at reading his audience, and he noticed that the crowds would react less when they saw that he was enjoying his treatment.

It was this revelation that would lead him to adopt the deadpan expression that he’d eventually become so closely associated with. While anyone who knew him behind the scenes would know that he was always a fun-loving and exuberant man, he became the Great Stone Face in his art, making his ludicrous stunts all the more absurd.

Sign up to our newsletter.

History’s most fascinating stories and darkest secrets, delivered to your inbox daily. Making distraction rewarding since 2017.

Off the Stage and in Front of the Camera

Keaton performed with his parents for his entire childhood, but his father’s increasing alcoholism eventually put a strain on the trio’s working relationship. Finally, in 1917, Buster had had enough and decided to set off on his own. He was 21 years old.

He initially headed to New York City to become a Broadway performer, but not long before he was supposed to start his first production, he had a chance encounter with one of the biggest stars in the world at the time, Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle. Keaton’s father, a lifetime Vaudevillian, had always been against the new-fangled medium of “film,” and Keaton shared his reservations—but the larger-than-life Arbuckle intrigued him nonetheless.

So the story goes, Arbuckle piqued Keaton’s interest in film during their first meeting, but the Great Stone Face wasn’t convinced. He asked if he could borrow one of Arbuckle’s cameras, and the comedian obliged. Keaton, whose childhood had instilled a strong “do-it-yourself” ethic, took the camera back to his hotel room, took it apart piece by piece, then managed to completely re-assemble it. With a newfound understanding of how the device worked, Keaton took it back to Arbuckle the next day and asked for a job.

Arbuckle must have seen something in the young Vaudevillian, because he gave Keaton what he asked for. Keaton made his first film appearance in a short called The Butcher Boy, filmed in 1917, the same year that he set out on his own.

The Best of the Best

People today associate the life of an actor with glitz and glamor—that wasn’t exactly Keaton’s experience. Slapstick was the name of the game in those days, and while Keaton was no stranger to the style, The Butcher Boy was a little extreme, even for the kid whose dad whipped him around theaters since before he could remember.

Getty Images Buster Keaton with his wife, Natalia Talmadge

Getty Images Buster Keaton with his wife, Natalia Talmadge

The movie saw Keaton doing absolutely miserable stunts, including getting dunked in a vat of molasses and bitten by a dog. If an actor today was given the same treatment, they’d sue for damages—but Keaton was hooked.

He stayed working with Arbuckle for two more years, making $40 a week and appearing in many more shorts. He earned a reputation as one of the best gagmen in the business, famous for the sheer audacity and creativity of his stunts.

It wasn’t long before Keaton got the chance to truly make a name for himself. Arbuckle moved onto other projects, leaving an entire filmmaking operation with no creative head. Joseph M. Schenck, the studio executive who’d held Arbuckle’s contract, saw that he had something in Keaton. In 1920, he created Buster Keaton Productions and gave Keaton the reins to start making his own movies.

The following decade would see Keaton’s greatest work, culminating in the 1927 classic The General, but there were storm clouds on the horizon. A series of career failures and two tumultuous marriages would see him descend into alcoholism and bankruptcy. A decade after being one of the world’s biggest stars, Keaton would be living in near-obscurity, struggling to eke out a living in a world that had passed him by.

Continued in Part 2.